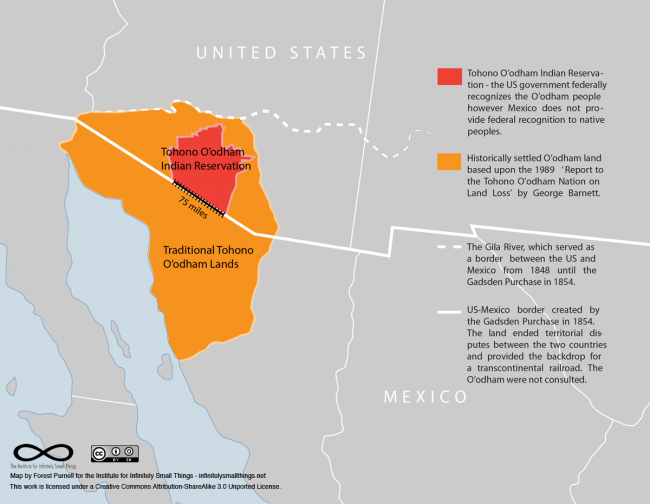

In April, as border patrol agents began to separate migrant families who risked their lives to reach the United States at the border, a group of men from the Tohono O’odham Nation trekked 300 miles in the opposite direction—from Arizona Upland to the salt fields at Mexico’s Sea of Cortez. This was the eighth year they’d undertaken the Tohono O’odham Men’s Salt Pilgrimage, which has gained new significance for an Indigenous people cleaved in two by the U.S.-Mexico border, and threatened by Trump’s plan to build an “impenetrable” wall across 75 miles of their reservation.

For thousands of years, the Tohono O’odham, which in the O’odham language means “desert people,” developed patterns of seasonal migration that enabled them to survive in one of the most arid swaths of North America, stretching roughly from Phoenix, Arizona to Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico, and from the Gulf of California in the west to Tucson in the east. Today, this extensive homeland has been reduced to the Tohono O’odham Indian Reservation, whose 10,000 residents live on nearly 4,500 square miles of southern Arizona—the third largest reservation in the United States. On the other side of the steel beams and barbed-wire fences, an estimated 2,000 O’odham in Sonora live without access to the reservation’s medical and educational services, and without recognition of their land rights by the Mexican government, which still calls them “Pápagos”—a misnomer imposed by Spanish colonizers.

Since Trump’s election, O’odham on both sides of the border are leading an increasingly outspoken struggle to defend their land and way of life against threats of its destruction—both from a fortified wall that would further divide them, and from the environmental consequences that appear to be deepening during the presidencies of Trump and his Mexican counterpart, Enrique Peña Nieto.

One of the O’odham’s most emblematic struggles is for the continuation of their transnational salt pilgrimage. For the O’odham salt is sacred, and for their ancestors the salt pilgrimage was both an initiation ceremony for young men and a way to gather the vital mineral used for healing, food preservation, and trade with other peoples. Today, the pilgrimage bisects biometric checkpoints and narco-trafficking routes that have dismembered traditional O’odham territory, culminating in the salt flats where companies are profiting from their sacred minerals.

Since April 2017, the La Borrascosa salt mine has been operating on 66 hectares of the salt flats, which have a long history as a sacred site and destination of the O’odham pilgrimage. The mining site is also located within the Upper Gulf of California Biosphere Reserve and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Even as the mine’s owners—a well-connected Sonoran businessman named Jesús Pedro Villagrán Ochoa and his partners—seek to expand their operations sevenfold, tribal leaders and environmental advocates say this extractive project violates Mexican and international law and should never have been approved in the first place—not without the required consent of Indigenous peoples, and not on a protected area with a rich archaeological, religious, and environmental legacy. That the mine was authorized regardless points not only to the rife corruption in Mexico’s environmental sector, but also to international conservation policies tipped increasingly in favor of corporate interests, its opponents claim.

On the Tohono O’odham Indian Reservation in Sells, Arizona, pilgrimage leader Ken Josemaria and medicine woman Mary Garcia prepare traditional tobacco and begin to weave together the tale of their ancestors’ journey from desert to ocean. “Hundreds of years ago,” Ken tells me, the salt pilgrimage “was the initiation for a young male to gain his position in the community.” Back then, young men had a choice between traversing the desert for salt or going to war with the Apaches. But Ken, who is a veteran of the U.S. army, said the pilgrimage was not unlike training for war: the men, known as salt-runners, ran through bone-dry lands “with four or five hours of sleep a day…the more difficult their journey was, the better the blessing.”

The journey to the salt fields was essential for the physical and cultural survival of the O’odham. This migratory desert tribe used salt to maintain electrolyte and fluid balance during the scorching summers, to prepare food preserves for the rainless winters, and to heal wounds and trade for goods year-round. The pilgrimage was also a time for the O’odham to ensure they were in tune with the unique cycles of their desert ecosystem and to assess their spiritual well-being.

For this particular ceremony, says Mary, the spiritual work centers on the suffering that Indigenous men have experienced through generations of colonial violence. While O’odham women participate in other tribal traditions, they do not partake in the salt pilgrimage. Even so, the strength for the ceremony comes from the women who pray for and protect the salt runners; “[the men] see the heart in us as the only way to grow,” Mary says.

Last April, some of the salt runners joined the pilgrimage in the Mexican border town of Sonoyta, Sonora, as their immigration status barred them from participating in Arizona. Pilgrims who speak both English and Spanish helped to facilitate communication between those speak only one language. Their shared journey through the Sonoran Desert forced the pilgrims to contend, first, with the walls and fences that have cut their homeland to pieces, and second, with the unequal toll this dismemberment has taken on opposite sides of the border.

On the U.S. side, the Tohono O’odham Indian Reservation has a hospital, several health clinics, and a community college where tribal members can learn the O’odham language. But in Mexico, the O’odham are far fewer and more spread out, with minimal political capital in the state of Sonora. Many on the Mexican side struggle to obtain tribal membership and a visa so they can access employment as well as medical and educational services in Arizona. In Mexico, the O’odham language has nearly disappeared, and the elders who could help revive it are out of reach on the other side of the border. Mary affirms that O’odham in the United States must “accept the O’odham on the Mexico side, because at one time we were families…And this is what the ceremony has brought back.”

O’odham salt runner Rafael Monreal Tamayo, a Mexican citizen whose family claims land on both sides of the border, watched a power shovel claw at Salina Grande—one of several salt fields where his people hold their annual ceremony. “It’s an emotional and impotent feeling,” Rafael tells me in Spanish. “Seeing this destruction and contamination, seeing that they don’t care about our traditional practices and our sacred sites—there’s no name for this feeling.”

The salt flats first became a digging site in 1967, when Mexican authorities granted a standard, 50-year permit for the exploitation of salt at the La Borrascosa mine. The low-tech operation tapered off in the 1980s, and in 1985, Jesús Pedro Villagrán Ochoa, a lawyer and businessman with offices in Sonora’s capital city of Hermosillo, purchased half of the rights to the concession. In December 2016, Mexico’s Ministry for the Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat) approved a new, five-year permit for the mine. In April 2017, Villagrán Ochoa and his business partners resumed operations with heavy machinery. Local landowners who keep track of cargo exiting the mining site estimate that workers extract around 40 tons of salt each workday, or approximately 10,000 tons annually. Their profits from this venture have not been made public.

The salt flats form part of a coastal wetland system protected by the Upper Gulf of California Biosphere Reserve. Federico Godinez Leal, former director of the neighboring Pinacate nature reserve, explains that in 2009 the area was designated for protection under the UN Ramsar Convention on Wetlands due to its remarkable ecology. “That there are natural freshwater springs there in the salt flats is extraordinary,” he says, “but it’s scientifically justified.” Millions of years ago the Colorado River had its estuary here, and its pristine, potable water still flows underground today. The surfacing of this freshwater forms the hard layer of salt commercialized by Villagrán Ochoa and his associates.

Subterranean drinking water also enabled survival for the O’odham’s ancestors as they migrated across a parched region of lava and dunes. Alejandro Aguilar Zeleny—a researcher at Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) who in 2017 oversaw the publication of a report on the cultural value of the salt flats—confirms archaeological evidence of the O’odham’s network of trails throughout the Upper Gulf Reserve. The O’odham’s presence contributed to the area’s designation as UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005. “From our point of view as anthropologists,” he tells me, “[the mining concession] should not have been granted. The simple fact of understanding where these projects are located should be sufficient to not even consider it.”

Biosphere reserves typically have a management program that divides the protected area into zones according to which types of activities are permitted and prohibited. Godinez explains that when the Alto Golfo Reserve’s management program was updated in 2007, loose and contradictory zoning regulations for Salina Grande, where the La Borrascosa salt mine is located stood out as a red flag in the “much more flexible” plan. On the one hand, the mine is included within a zoning area that permits mining. But at the same time it is zoned within an area where only exploratory activities—and not extraction—are allowed. Godinez says that nature reserve staff have issued conflicting statements on whether or not mining is permitted at the O’odham’s sacred site. The staff could not be reached for comment.

One employee of the Protected Areas Commission in Sonora claimed that Villagrán Ochoa was only awarded a permit because of connections to Sonoran Governor Claudia Pavlovich. A member of Mexico’s ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), Pavlovich has reportedly been embroiled in multiple scandals replete with free trips to Las Vegas and suitcases full of money. There are six additional mineral exploration permits at Salina Grande—four of which are partially owned by Raúl Elias Favela, a businessman and cattle rancher who has appeared at promotional events with Pavlovich.

The Tohono O’odham tribe and other local landowners are clear that in a case with many irregularities, their struggle to defend the salt flats is only just getting started. They believe their fight has implications far beyond the Upper Gulf of California. Throughout the world, biosphere reserves established in the 1970s under UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere Programme have more flexibility than national parks or wildlife refuges, with a structure that balances conservation with research and sustainable development. This means they have a “core zone” or strictly protected conservation area, surrounded by a “buffer zone” that allows non-contaminating activities, and a “transition area” that promotes “ecologically sustainable” development projects.

In practice, this structure has been increasingly subject to corporate influence. At the international level, UNESCO has worked to establish guidelines for “sustainable” mining on biosphere reserves, in collaboration with multinational companies that have a dismal record of environmental destruction and human rights violations. In Mexico—where mining is allowed on protected areas so long as it doesn’t modify the landscape or negatively impact ecosystems—mining lobbyists have shaped management programs through closed-door meetings, thus ensuring approval of extractive projects in protected areas regardless of their environmental impacts.

In 2013, Mexico had 1,282 mining concessions within its protected areas, and an additional 2,031 concessions falling partially within its borders. By 2016, the administration of current President Enrique Peña Nieto had sliced funding for Mexico’s environmental ministry in half, leading advocacy groups to denounce the reduction of funding and personnel for protected areas as a strategy to pave the way for resource extraction.

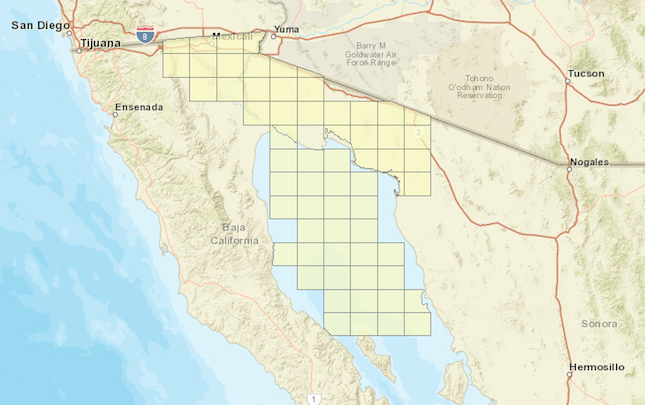

While La Borrascosa is a relatively small extractive project, land defenders see it as a warning sign in a protected area that is still largely free of open-pit mines and offshore drilling rigs. Their concerns appear to be justified. In 2002, Villagrán Ochoa and his partners were awarded a 50-year exploration permit on an additional 725 hectares of the O’odham’s salt flats. While their 2016 application to begin commercial extraction on this larger parcel was denied, 50-year concessions give mining companies ample time to wait until more favorable economic conditions arise. As of 2017, 46 additional mining concessions had sprung up within the limits of the Upper Gulf Reserve.

An interactive map of concessions monitored by the Mexican government reveals that large swaths of the land claimed by the O’odham in Mexico, including the nature reserves, are already slated for the exploitation of oil, natural gas, and other minerals. These mining “assignments”—issued exclusively by the Secretariat of Economy to the Mexican Geological Service “with the aim of identifying and quantifying the Nation’s potential mineral resources”—ignore existing prohibitions on mining within large areas of the reserves.

While the administrations of Trump and Peña Nieto have presented the Tohono O’odham with a new set of challenges, activists also see unprecedented opportunities to grow their recently emboldened land defense movement. In the United States, O’odham leaders have made national news as they protest Trump’s proposed border wall and denounce his failure to consult with the tribe. In Mexico, the O’odham partnered with the Center for Biological Diversity to file an endangerment petition for the Pinacate Reserve, whose wildlife would be imperiled by the impassable, 30-foot high barrier. The O’odham continue to work with the Center as it sues the Trump administration for environmental violations. Ken, the salt pilgrimage leader and U.S. veteran, sees that the ongoing politicization of the border under the Trump administration will bring the struggle of the O’odham people into the spotlight.

The small O’odham population in Sonora is also redoubling its efforts to gain recognition of their identity and land rights. Mexican tribal leaders have built alliances with local landowners who also oppose the salt mine at Salina Grande, and in April they erected a sign at the site that reads: “Tohono O’odham Nation Sacred Site, No Trespassing.” In March, the assembly of the Tohono O’odham tribe in Mexico passed a resolution condemning the Mexican government’s weak monitoring of protected areas on their traditional territory, and calling for greater O’odham participation in management and decision-making. Recently, the tribe conducted its own census in Sonora with the aim of getting a more accurate picture of their population and improving organization. The usually quiet tribe has also started to share their story more frequently with news media in both English and Spanish.

According to Zeleny, the anthropologist, rather than permitting short-sighted extraction on O’odham sacred sites, we should heed the timely lessons offered by this desert people, “who have shown for centuries that in this region it is possible to live without damaging it, influencing it, or looting its resources,” he said. “As a society faced with the risk of climate change, we cannot disregard any human experience that teaches us how to live more adequately in harmony with nature.”

For their part, Mary says the Tohono O’odham are ready to offer such lessons: “We have to remember all of the times when creator said that the different color people are also your people…And when they come back to you they are going to be the ones that have no soul, and you’re going to have to teach them and reteach them that.”

Samantha Demby is an activist, writer, and translator whose work focuses on land struggles, resource extraction, and border militarization in the Americas.