This piece appeared in the Fall 2024 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

Leer este artículo en español.

When soldiers and tanks descended upon the iconic Plaza Murillo in La Paz in a surreal kind of reenactment of Latin American coups of decades past, Bolivian feminist activist María Galindo was in Austria, presenting her latest film. She quickly called out the disturbing events for what they were. “Bolivia has not suffered a coup against the state, but a coup against society,” she wrote the next day for the Spanish paper El Salto. “Bolivia is not a democratic regime, but a machocratic one where the macho men of the day play with our lives while disputing with each other the length of their penis.”

Just as quickly as it had begun, the June 26 military incursion undid itself in reverse motion: the soldiers retreated from the plaza under orders from a new commander, tanks curled their way back to their barracks, and a now disgraced general betrayed his commander in chief as he was detained just hours after the incident began.

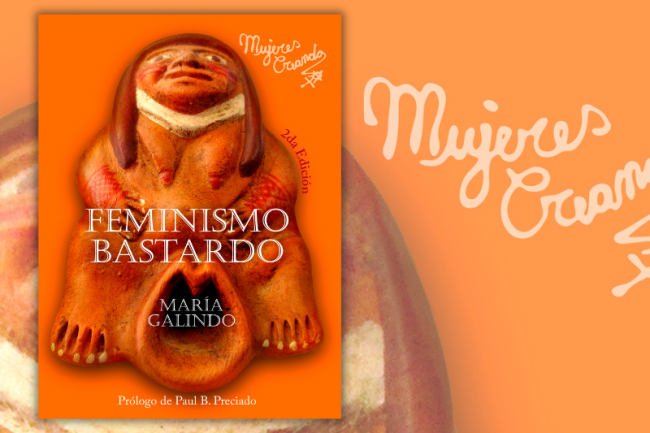

Amid a swell of speculation, Galindo warned that the coup was “still active,” saying we had yet to see the outcome of this charade. Bolivia, she maintains in her provocative 2021 book Bastard Feminism, is made up of “a colorful, theatrical, and creative social scenography,” but one that is “also very destructive and tyrannical.” While social media users and political pundits concocted conspiracy theories to explain the bizarre coup attempt, Galindo, as always, cut to the point: “Yesterday was a dangerous, fascist, violent, and authoritarian exercise, and what it wants from us is training to accept living this way.”

In her own words, Galindo is “a cook, street agitator, graffiti artist, radio broadcaster, writer, and public lesbian.” She is also “a filmmaker, a gossip, a loudmouth, a malcriada, [and] a bastard” who hosts a popular daily radio program, “El Deseo,” that aims to “celebrate the presence and warmth of the utopian fire in society.” In 1992, she cofounded Mujeres Creando (Women Creating), a radical anarchist feminist collective and cooperative space in La Paz that has become synonymous with the most irreverent, innovative, disruptive, and creative threads of Latin America’s feminist awakening.

Today, Galindo is a widely known public figure whose incendiary reach extends far beyond the artificial geographical boundaries of the plurinational state. This past carnival season, entire comparsas (dance troupes), ranging in age from young girls to middle-aged women, styled themselves in homage to Galindo’s iconic dress and intransigent attitude. In the prologue to her book Bastard Feminism, writer and philosopher Paul B. Preciado affirms that Galindo and Mujeres Creando “have elaborated a singular political, artistic, and literary practice” that “stands in opposition to the institutionalization and normalization of feminism and Indigenism as state policies.”

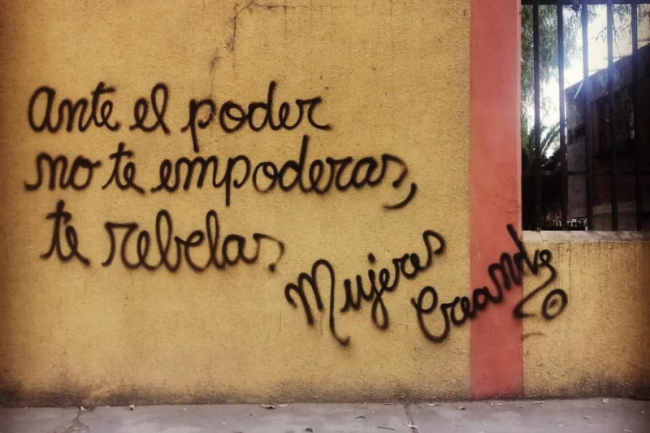

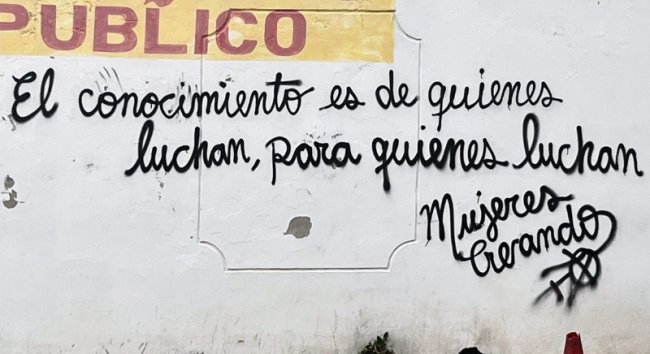

Ever critical of politics and the elitism of academia, Galindo’s platform is the street, the plaza, the mercado popular, the brothel, the public bus, and other spaces that, although often seen as marginal or even disparaged, are in fact places where people live and work and enact everyday forms of resistance. “Knowledge,” writes Mujeres Creando in their emblematic cursive graffiti that adorns the walls lining city streets across the country and beyond, “is by those who fight, for those who fight.” Such quotes exemplify the movement’s bite-sized and accessible form of feminist theory meant to inflame the popular imagination.

In this interview, Galindo looks back on the Feminist Political Constitution drafted by Mujeres Creando alongside the Constituent Assembly in Bolivia that led up to the refounding of the republic as a plurinational state in 2009. While Bolivia’s new charter was widely celebrated as one of the most progressive in the world, the Feminist Constitution called attention to the voices that were left out of the process. The document invited citizens to think outside the colonial logic of the nation-state and its structures of surveillance, censorship, and subordination. “It is not precisely a model of the state that is under discussion,” writes Galindo in her latest book in a section on interculturality, diversity, and plurinationality, “but social relations seen beyond the categories of class, race and gender” that mark large sectors of the population as “other.” “Plurinationality,” she continues, “does not cease to also be a patriarchal project because it succumbs to a masculinist understanding of the ‘question of Indigenous peoples.’”

The Feminist Constitution “was drafted in a large kitchen while we peeled the potatoes and the children helped with the peas,” the collectively written document begins. “The form of approval was by consensus and the rotating use of the word. No one was allowed to speak on behalf of anyone else.” The text declares Bolivia as a “free, independent, sovereign, and pluricultural country in all possible senses and directions” and summarily dissolves the military, police, and political parties. It prioritizes health and education for all, protects the rights of animals, enacts mandatory sex education and “the right to know our bodies without taboos or humiliation,” and abolishes marriage as an institution of women’s oppression, among other innovative proposals. As a critical, playful, and utopian exercise, the Feminist Constitution centered the voices of women and sexual dissidents and illuminated the transformative potential of a constituent process that was “mutilated by the calculus and ambition” of “a pact of men.”

Today, as the MAS implodes at the hands of these same men, the utopian vision embodied by the Feminist Constitution is more salient than ever. We have a responsibility, as Galindo writes in her book, “to delineate non-violent forms of struggle… with new poetics where our vulnerability is our greatest strength.”

This interview was conducted via email in May 2024. Our conversation has been translated from Spanish and edited for length and clarity.

Julianne Chandler: What does plurinationalism mean to you? What does it mean to conceptualize it from a feminist perspective?

María Galindo: I prefer to speak from the point of view of the crisis or the end of the cycle of the nation-state on a global scale. I prefer to speak of supra-state structures such as colonialism and capitalism that have turned nation-states into mere administrators of a model in which their decision-making margins are nonexistent. This is especially the case in southern nations. That is to say, the main problems surrounding the state and nation are not solved by plurinationality.

However, if we were to recover the concept of the plurinational state, I would propose the following: the plurinational state means having legal pluralism, educational pluralism, and pluralism in the health system as basic requirements to start talking about plurinationality. If these three forms of pluralism are not concretely present, the plurinational state has no content or foundation.

JC: How has this proposal been misrepresented or distorted by the state?

MG: I don’t think it has been distorted, but at least in the Bolivian case, there has been a perverse use of the term to camouflage it within the same nation-state structure. Note that the state’s central axis is a nationalist, chauvinist, patriarchal discourse.

Many will say that the problem is that, in reality, Bolivian plurinationality is mere rhetoric because it has not really materialized in the management of state power (and they are right). In any case, the wounds I am talking about—which are installed in subjectivity and affectivity itself—are not resolved by changing the name of the state.

Read the rest of this article, freely available for a limited time.

Julianne Chandler is a feminist writer, editor, and journalist based between New York and Cochabamba, Bolivia. She is an editor at NACLA.