This interview has been translated from Spanish by Nancy Piñeiro. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

This is the third installment in a collection of interviews with Indigenous and feminist media makers and community organizers in Bolivia. They explore building community media, Indigenous liberation, and feminist social change through grassroots journalism and people's movements. Read the other interviews here.

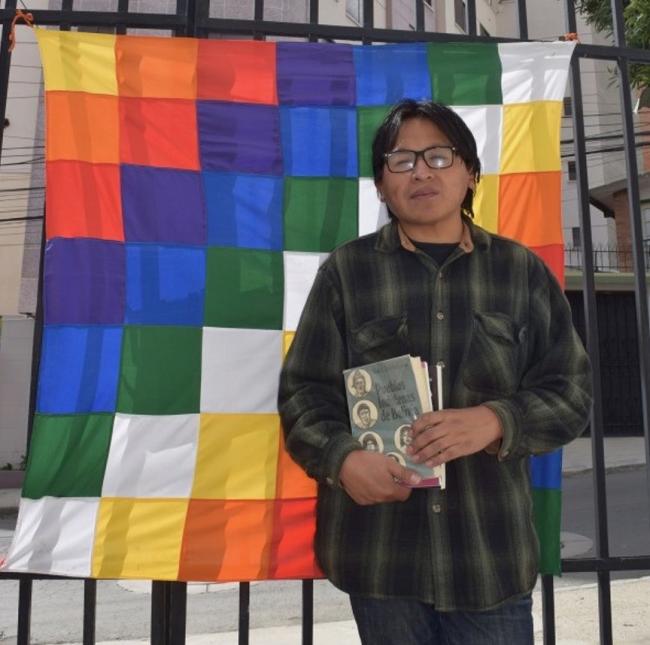

Indigenous thinker, organizer, and writer Wilmer Machaca joined the political currents of Indianism in the early 2000s when rebellions against neoliberalism and state repression filled the streets of Bolivia. He was inspired by the late Indigenous leader and thinker Felipe Quispe and moved by the public debates in plazas during that tumultuous time.

Indianism and Katarism, named after the 18th century anti-colonial Indigenous leader Túpac Katari, are currents of thought, action, and politics aimed at Indigenous liberation and decolonization, with their roots going back centuries. In Bolivia in the 1960s and 1970s, these currents were tied to independent campesino union movements, political parties, and the development of mass Indigenous struggles.

Now, Machaca explains, there is “a more contemporary Indianism that understands that the decolonization process doesn’t necessarily imply returning to a rural space, but that it can have different goals and spaces where this type of issue can be translated.”

“There are indeed several Indianisms,” he says. “I think at least this new generation is a mix between the warrior-like Indianism of Felipe Quispe and the need to look beyond the rural or unionist perspective, to a more urban and power-oriented view like that of [Pukara Magazine editor Pedro Portugal]—an Indianism with a political and economic power-based perspective.”

Machaca and other thinkers explored such political philosophy and strategy in their debates, publications, and writing, eventually forming the digital outlet Jichha, a space for debate, online diffusion of books and texts, and exploration of Indianist decolonization and liberation.

In this interview, Machaca discusses the work of Jichha, how it supports movements in the streets, and how it takes on academia’s hegemony around the production of knowledge. Machaca also talks about how the media outlet is a space for building Indigenous political power in Bolivia and across the Andes.

Benjamin Dangl: Could you share your perspective of Jichha as an organization that promotes a wide reflection on Indigenous movements and thinkers in Bolivia, as a space that supports the movements, and as a non-traditional media outlet? Could you describe Jichha’s role in this context?

Wilmer Machaca: I think Jichha was born as a very Aymara and Indianist media, as an Indianist-Katarist outlet. We knew there were a lot of productions made by anonymous people and also by subaltern people in academia and political spaces. Our idea was to show this Indianist and Katarista content.

But everything has its limits, so I think that with activism and the dissemination of bibliographic material mostly, Jichha started to widen its perspective from an Aymara, Indigenous one, to a more international one.

Jichha has allowed us to build connections. Its followers are mostly in the Andean region: the Peruvian south—Cuzco, Lima, Tacna; the Argentine north—Humahuacca, Salta, Jujuy; and the Chilean north—Arica and Iquique, Putre.

In a way, Jichha has been able to generate a sort of community to share. We have sister organizations with which we organized trainings, essay competitions with brothers from Ecuador and Peru, and the like. This digital space has allowed for this type of connection.

I don’t know if it’s digital media but it’s a space where we can join the Andean regions, Aymara and Quechua, and generate solidarity with other peoples. When countries go through a crisis, for example, in 2022-2023 during the Peruvian crisis or 2023 in Ecuador, we share our concerns and understand that beyond the republican borders that have been established for so long, there’s a sense of a common identity, of a nation in the Aymara case. We try to have a regional perspective more than a local one.

BD: You share a lot of historical and critical texts about Indianism/Katarism through Jichha. Could you explain the role of Jichha as an alternative to institutional spaces such as universities and other traditional media? If I understand correctly, you’re trying to democratize knowledge through sharing these texts, right? Could you speak about the philosophy behind this?

WM: I think that we maintained this idea from the beginning. We come from a place, so to speak, of little privilege, in the sense that having a good education requires a certain level of economic means and also the chance to have access to bibliographic materials. At least in my generation, it was a bit difficult. So being able to think about education, politics, and philosophy is indeed a kind of privilege.

We wanted to disseminate not only Indianist-Katarist materials, but anything related to political perspectives, more than academic ones, so we could have this balanced level of education and be able to dispute these spaces that have usually been occupied by the same type of people.

Jichha’s perspective has always been to educate ourselves, develop critical thinking, and consolidate our own project of a country. It’s not so much an activist or communications media, but more like a truly political perspective: to educate ourselves and occupy these spaces, which up until now have usually been controlled by privileged, mostly middle-class people.

I think new generations now understand that we, as Aymara, Bolivian, and Indigenous people, also must take these spaces. Not only traditional places where you imagine Indigenous people: unions, neighborhoods, social movements, etc. Yes, that’s the traditional academic, folkloric view. Jichha’s perspective is more political and power based.

BD: Considering your trajectory as militant, activist, and thinker since 2000, and having created Jichha, what is your opinion on the importance of creating these spaces of social transformation? Jichha is not very common when compared to other media and spaces that reflect racism, classism, and inequality in the country. But Jichha and other Indianist spaces are developing another vision for the country. What is your perspective on the importance of such work?

WM: I think it’s important, especially in these times. There’s a crisis of traditional media, not only in Bolivia but in the world as well. There’s a lack of credibility in traditional media, and also people want to keep informed but in accordance with their social, economic, or regional conditions.

I think in this sense, Jichha has given a voice. It has occupied a space that other traditional media were not able to occupy, of course with some limits. That’s why we generated a type of community. In the digital space, there are hundreds of communities of one type or another. This is what internet and socio-digital media allow for, people can build according to their perspective and worldview.

There is a possibility of creating your own alternative media, communications media, or a digital platform where people can identify with the material. There is a very diverse consumption, and transparency plays an important role, in addition to persistence.

Jichha has many years of activism, but there are experiences that are born and die in a month or a year. Any project today has to be constantly regenerated; this is a kind of commitment. As with any communicational, alternative media, if there isn’t a prolonged commitment, it won’t last long. Jichha has no funding, it doesn’t have advertising. Our commitment is what sustains it over time; it's self-managed through the time and work we can dedicate to it and a lot of heart.

I think interesting times are coming, not only in Bolivia. Jichha’s strength is in being a “hinge” space between the previous generation, our elders who had links to social grassroots organizations, and the new generations that are more connected to digital tools. We think we are in the middle and we understand the importance of both. We should be in digital spaces but without losing our connection with social organizations and the street. It’s really important to keep that connection.

Benjamin Dangl is a Lecturer of Public Communication and Journalism at the University of Vermont. He has worked as a journalist across Latin America for over two decades covering social movements and politics. Dangl’s most recent books are The Five Hundred Year Rebellion: Indigenous Movements and the Decolonization of History in Bolivia and A World Where Many Worlds Fit.