If you live in a Mexican border city and have access to the U.S. market, goods, and even employment opportunities, you are more likely to have higher socioeconomic status in Mexico compared to individuals who either remain undocumented in the U.S. or live in Mexico and are unable to cross the border. However, many transborder and undocumented workers are subjected to low paying jobs in the United States, labor exploitation due to limited rights protections, and other forms of oppression such as racism, xenophobia, or gender violence.

Regardless of the political party in power, the United States has increasingly criminalized labor from migrant workers and their access to welfare programs, including through policies such as the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) and the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act (PRWORA). Yet the main constant over the years has been the relatively free flow of capital across borders. Transnational companies, whose existence depends on the historical and sustained exploitation of Indigenous and marginalized communities, continue to reap the benefits of open borders even as these same borders are increasingly militarized against human mobility.

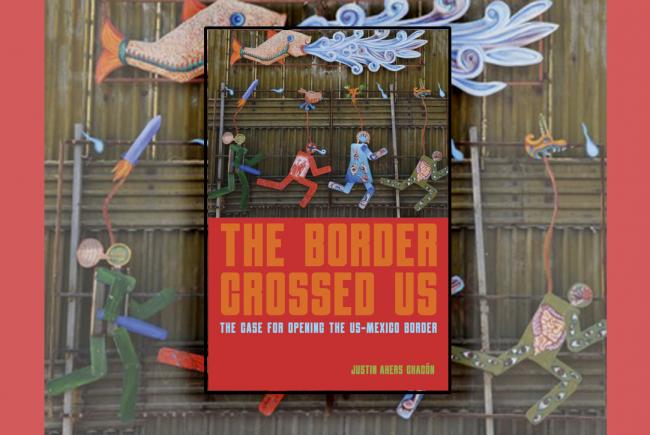

In The Border Crossed US: The Case for Opening the U.S.-Mexico Border, scholar-activist Justin Akers Chacón provides a historical account of the various capitalist and imperialist forces that have made the border permeable for trade and transnational corporations. At the same time, both Mexico and the United States have eradicated human rights protections for migrant workers to suppress class consciousness and political mobilization.

Akers Chacón’s insightful account of migrant worker exploitation takes a critical approach: he argues that the U.S. migra-state is bolstered through pervasive worker exploitation by capitalist interests from Mexico and the United States. And he points to multinational and historical repression stemming from colonialism as the root causes of the state violence against undocumented migrants that we see today. However, these processes have simultaneously produced links of transnational solidarity among migrant workers who have engaged in political movements and strikes advocating for worker justice on both sides of the border. Thus, Akers Chacón highlights how transnational workers are bound through shared struggles against exploitation—and through the possibility for a worker-led movement for border abolition.

Open Borders for Capitalists; Closed Borders for Workers

At the core of The Border Crossed US is the theme of labor exploitation. Akers Chacón argues that by denying migrants livable work conditions, the capitalist class expands the state violence and class warfare already enabled through colonialism and imperialism.

“Building on the construction of disempowered systems of slave and captive labor, English colonial and then United States immigration policy was invented and implemented within this framework,” he writes. “As a result, immigration policy was crafted at each phase of capitalist development based on legal frameworks that excluded, subdivided, and hierarchized migrant workers along racial and national lines.” The construction of racialized illegality was thus instrumental for giving the U.S. capitalist class access to cheap labor from migrant and racialized communities, who were instrumental during the era of industrialization.

The bourgeois leaders that remained after the Mexican Revolution also consolidated the suppression of class consciousness. Even after porfiristas left power, many of whom were educated in U.S. elite institutions, they retained influence by constructing Mexico’s financial system. During the decades-long reign of the PRI in Mexico, the two nations worked in collaboration to consolidate capitalist development in the Americas through free trade agreements.

Income inequality increased after the 1994 launch of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which displaced Indigenous and impoverished communities throughout Mexico. Many of those displaced, including braceros, were forced to work in maquiladoras for low wages. Women who relocated to border cities like Ciudad Juárez to find work in maquiladoras were often victims of femicides, forced disappearances, and employer abuse. Nearly three decades after NAFTA began, more than half of Mexico’s population still lives below the poverty line and authorities have criminalized unions. NAFTA was also implemented during a period of border militarization through “prevention through deterrence” policies, which pushed migrants to cross the border through lethal routes along the U.S. desert. Together, NAFTA and border militarization operations, such as the 1994 Gatekeeper, further criminalized undocumented migration despite the continuing U.S. demand for cheap labor from migrants.

In September, images of a new $21 million Amazon warehouse set to open in Tijuana have circulated in the news and on social media. This warehouse, which is protected by a fence, is surrounded by impoverished families whose homes are made out of cardboard, tarp, and wood scraps. These homes are often demolished by the rain, and many families do not have access to running water and electricity. Although policymakers and spokespersons for Amazon boast about the company’s ability to generate new jobs, the average minimum wage worker in Mexico earns anywhere between $6 and $9 per day, often working for more than eight hours per shift.

Border cities like Tijuana are increasingly attracting transnational companies. After constructing warehouses and headquarters in some of the most impoverished neighborhoods in Tijuana, these corporations can be expected to overwork their employees to maximize profits with little to no oversight from Mexican officials. Tijuana is also fertile ground for real estate developers, threatening to gentrify neighborhoods where working-class families have lived for generations. As developers build an (expensive) vertical city and capitalist exploitation continues to squeeze local workers, Tijuana is rapidly becoming unlivable and unaffordable.

Despite this transnational agenda to repress worker’s rights, Akers Chacón identifies links of transnational worker solidarity. In 2019, strikes occurred simultaneously in Mexican maquiladoras and GM Auto plants. Akers Chacón demonstrates how—despite the pervasive corruption in Mexico’s sindicato leadership, made up of many members of the bourgeoisie—workers have successfully shut down plants and demanded better working conditions. Workers have engaged in such resistance even when they have risked being fired or faced repression from the military and police during union gatherings. Here, The Border Crossed US provides a vision for transnational solidarity and a border abolition movement rooted in workers’ struggles.

Racialized Criminalization of Migrant Workers in the U.S. and in Mexico

The second section of The Border Crossed US focuses on the various policies that have constructed the illegality and the criminalization of undocumented workers. Under IRCA, employers could require workers to provide citizenship documents, effectively criminalizing and lowering the wages of undocumented workers. This component of IRCA served to appease companies that wanted to ensure maximized profits through cheap labor from migrant workers. United States-based unions supported IRCA as a whole, the amnesty component that regularized some migrants’ immigration status, and the criminalization of future migration.

As Akers Chacón rightfully notes: “Illegality denies workers basic rights to organize unions, collectively bargain, petition for grievances, or in any way leverage their class power for higher wages, better working conditions, or their political rights. In effect, it also makes them permanent ‘at-will’ workers.” Undocumented workers in particular experience compounded vulnerabilities under the carceral state and employer exploitation. When they demand more rights, they experience mass criminalization and retaliation from employers and immigration agencies. Many employers threaten to call immigration enforcement if workers demand better work conditions or even attempt to unionize. In response to immigrant rights protests in 2006, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents conducted a series of raids over the span of more than a year in workplaces where migrants overwhelmingly worked. These strategies, developed from counterinsurgency methods in Latin America, effectively transform immigration enforcement into a paramilitary organization with limited oversight over its operations.

In response to increased repression, many migrant workers have learned to police themselves and their behaviors as a “self-preservation mechanism,” modifying behavior to remain relatively invisible when their identities are considered suspect. Sociologists Cecilia Menjívar and Leisy Abrego have determined that these behavioral changes stem from what they call “legal violence.” Legal violence describes the processes through which legal systems normalize state and structural violence against migrants and how migrants themselves then engage in self-deprecating behaviors and internalize violence as part of their daily lives.

Transnational Workers Rights and Border Abolition

Akers Chacón’s work engages in conversation with political economic critiques of the carceral state, including Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s Golden Gulag, and the work of scholar-activists denouncing the imperialist root causes of the U.S. deportation machine, such as Harsha Walia’s Border and Rule and Alfonso Gonzales’ Reform Without Justice. Although this book deals primarily with the U.S.-Mexico border, Akers Chacón’s work provides a broader critique of the commodification of workers across international borders and systems aimed at suppressing class consciousness, such as the United Arab Emirates’ Kafala system that binds migrant workers to their sponsors or live-in care giver programs. The United Nations has identified that the Kafala system can serve as a pipeline for human trafficking for domestic servitude. And in Servants of Globalization, a study on Filipino domestic workers, Rhacel Salazar Parrenas finds that migrant workers who choose to leave their abusive employers are illegalized and subjected to deportation. Enriching these broader conversations, The Border Crossed US offers a timely Marxist perspective on the root causes of the (transnational) migra-state, from colonization to transnational capitalist exploitation. The book ends with a call to activists and workers to engage in a transborder labor movement as a means to counter global capitalism and to abolish the border.

Moving forward, this book can help researchers, advocates, and community members alike understand the effects of capitalism on migrant workers, with deep attention to the gendered and racialized ways workers experience the consequences of capitalism and imperialism. For example, nannies and housekeepers are rarely if ever afforded legal protections to confront exploitative work conditions and are often at the behest of their employers. Women domestic workers experience heightened vulnerabilities if they are undocumented or transfronterizas (living in Mexico but regularly cross to work). Many are robbed from experiencing motherhood themselves as they spend long hours in poorly paid care jobs, limiting their time with their own children.

During the pandemic, many migrants in the United States have fought eviction threats and been highly vulnerable to sudden layoffs. Meanwhile, the U.S.-Mexico border has remained “closed” to cross-border travel by non-immigrant visa holders (such as those who have tourist visas) since March 2020. Workers who do have the capacity to cross the border on a regular basis are significantly exposed to Covid-19 given that there is no social distancing in the pedestrian lines at land ports of entry. Yet, these limits to cross-border travel only apply to northbound travel; travel into Mexico is not restricted. We have thus witnessed how border enforcement officials have used a public health crisis as a pretext to once increase militarization and limit the mobility of the most vulnerable communities.

Akers Chacón ends with a discussion of the interconnectedness between movements to end the migra-state, police brutality, and U.S. detention centers. He reminds us that we cannot rely on the current political system to advocate for the working class. Rather, we must envision a world without borders and without a capitalist class. In short, border abolition and class consciousness go hand in hand.

Estefania Castañeda Pérez is writer and a Ph.D. Candidate and a writer at the UCLA Department of Political Science where she researches CBP’s border enforcement practices at land ports of entry and their impact on the transborder population and asylum seekers. Follow her on Twitter: @transb0rder