On August 19, 2007, attendees of Britain’s premier classical music festival, the BBC Proms, witnessed one of the most memorable concerts of its 100-year history. The performance, which included Shostakovich’s 10th Symphony and the Symphonic Dances from West Side Story, was delivered by the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra of Venezuela. Dressed in yellow, blue, and red and led by charismatic conductor Gustavo Dudamel, the group enchanted the radio, television, and live audiences. The British press called the concert “astonishing” and “sensational,” and described the young musicians as “extraordinary.”

The Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra is the flagship of Venezuela’s state-run youth music program, El Sistema, started by Venezuelan educator, musician, and activist José Antonio Abreu. Founded in 1975 as a group of orchestras mainly catering to the middle class, El Sistema came to international attention during the presidency of Hugo Chávez (1999-2013). Chávez invested heavily in El Sistema, prioritized its role as a social enterprise, and provided diplomatic support to help its orchestras begin touring internationally. The program, which offers classical music scholarships to the poorest Venezuelans, has directly inspired similar orchestras across the world, including in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom.

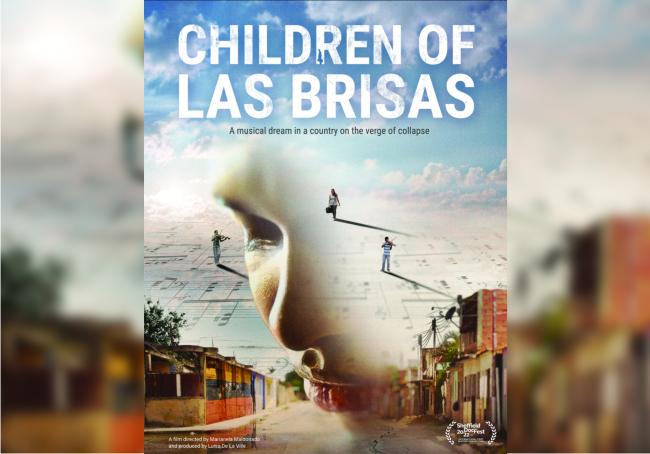

Children of Las Brisas is a feature-length documentary directed by Marianela Maldonado, a filmmaker who has previously written documentaries about her native Venezuela, and co-wrote the Oscar-winning animation of Prokofiev’s symphonic work Peter and the Wolf. Filmed from 2009 to 2019, Children of Las Brisas presents a lesser-known side of El Sistema. Set in the impoverished neighborhood of Las Brisas in Valencia, Venezuela’s third largest city, it follows the lives of three young people aspiring to become professional musicians through El Sistema.

Dissandra, Edixon, and Wuilly all had challenging upbringings. Two of Dissandra’s sisters died as newborns. Edixon—whose mother has congenital deafness—moved to Las Brisas after his father was killed by thugs. Wuilly’s parents, convinced the world was about to end, hid the family in a church and did not let them leave for six years.

“Music has not only saved my life,” Wuilly says at the start of the film, “but has changed my way of thinking.” He longs to be a concert violinist and play the solo of Felix Mendelsohn’s concerto in E minor. Dissandra, another violinist, says music “transports you into a wonderful world, full of fantasy, of emotions, of magic. You can express what you’re feeling. When you’re sad, you play with that sadness. But when you’re happy, that joy comes through.” Edixon, a violist, plays under the corrugated iron roof of his bedroom, and practices conducting with an energy inspired by Dudamel—an alumnus of El Sistema and now the music director of the L.A. Philharmonic and the Paris Opera.

The three young musicians’ aspirations are set against the precarity of the neighborhood of Las Brisas. We see streets submerged in water, shoes hanging from electricity cables, and bullet holes in walls. “You hear gunshots every night,” says Dissandra. “It’s as if they were semiquavers [1/16th musical notes].” As the documentary progresses, the day-to-day scarcities of post-Chávez Venezuela become apparent. Edixon’s family search in vain for flour, Dissandra can’t find medicine for her ill sister, and the camera pans along a line of people waiting to fill cooking gas cannisters.

Music is a dose of medicine, but it is not a panacea. After her mother loses her job, Dissandra begins playing at fancy restaurants, but the little money she makes is spent on the taxi home. Wuilly lives on the streets of Caracas, eating out of trash cans and playing (Mendelsohn’s violin concerto) for street change outside the Torre Lincoln. After Edixon’s grandmother loses her job, and the money from his state scholarship dries up, this charming, gentle boy joins the army. “There they feed and educate me,” he explains. “My family benefits from the food boxes that come to the battalion. My viola was my great love. I gave it up for a rifle.”

Children of Las Brisas eschews politics until it directly impacts the characters’ lives. Wuilly is, by far, the most politically active. He attends the Caracas street marches of 2017, wearing a tricolor jacket of the kind worn by El Sistema musicians on their foreign tours. Following the state’s murder of 17-year-old protestor and fellow violinist, Armando Cañizares, Wuilly marches with other members of El Sistema to protest Cañizares’s death. He walks and takes out his violin to play the mellow notes of one of Venezuela’s quintessential tunes, El Pajarillo.” “Maybe I’ll be killed, like Armando,” he says. “But if I’m going to die, I’ll die playing.”

That outcome is possible. Scores of riot police advance on Wuilly as he stands alone in the rain playing his violin. It is a kind of "Tank Man" Tiananmen Square moment, and became the emblematic photograph of the 2017 demonstrations. The government’s response to Wuilly’s peaceful, musical protest, is to have him arrested and tortured. He is released on the condition that he—by now an internationally-recognized figure—never play in public again.

Venezuela’s political, economic and humanitarian crisis is well known, but to see it through the eyes of talented young musicians is especially affecting. Of the film’s intimate moments, several stand out: Wuilly playing his violin in the garden, accompanied by his mother on the cuatro; Dissandra inspiring her younger sister to pick up the recorder; and Edixon longing for his deaf mother to hear him play more than just the highest notes. The access to the protagonists’ lives is remarkable, and a testament to the trust the characters had in the filmmakers. We are with Dissandra, Edixon, and Wuilly at very vulnerable moments—moments that a camera has no right to witness.

Where Children of Las Brisas could be stronger is in its portrayal of the politics of El Sistema. At the end of the film, the narration praises the institution uncritically and overemphasizes its opposition to the state. However, El Sistema is run by the ministry of social services and has long been used as a symbol of the Bolivarian state project. Some El Sistema musicians may have protested the death of Cañizares (who was one of their own) but it should be noted that—whether in fear for their jobs or out of genuine allegiance—many involved with the program are Chávez-Maduro loyalists.

This oversight is the one lax note in a brilliant, polyphonic composition that focuses on the lives of three courageous young people. As governments across the Americas struggle to support Venezuelan refugees, it provides a reminder of the hardship of daily life in the country, and of Venezuelans’ enormous potential. Dissandra, Edixon, and Wuilly are remarkable people. Children of Las Brisas is a remarkable film.

Daniel Rey is a British-Colombian writer and historian.