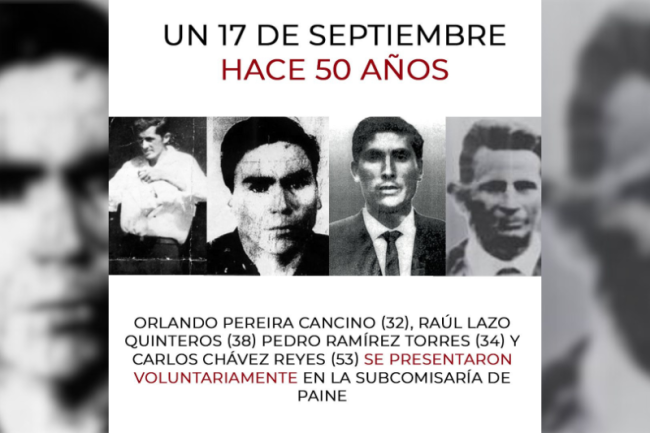

On the evening of September 17, 1973, Orlando Pereira Cancino arrived at his home in the small rural Chilean community of Paine, 30 miles south of the capital Santiago. He was 32 years old. Pereira had spent the day as he did most others, working at the asentamiento Paula Jaraquemada, a former latifundia estate that had been expropriated as part of recent land reforms and turned into a collective farming settlement. One week earlier, the military had seized power in a violent coup against Chile’s democratically elected Marxist president, Salvador Allende, who had carried out most of the reforms. The junta led by General Augusto Pinochet and backed by the United States had already dissolved the congress amid armed resistance in Santiago.

But Pereira, like many of his neighbors, had no known ties to any militant groups. So when the president of the asentamiento told him he had been ordered to report to the local Carabineros military police station, he went voluntarily. Pereira even washed up before leaving the house, according to a 2016 interview with his sister. It was the last time Mónica Pereira Cancino would see her brother alive.

“He never came back from there,” Mónica said.

The Carabineros detained Orlando Pereira that night, along with four other men from the asentamiento: his brother-in-law Raúl del Carmen Lazo Quinteros, Carlos Chávez Reyes, Pedro Luís Ramírez Torres, and Alejandro Bustos González. In the early hours of the morning, a group of Carabineros and civilians took the men from the station to Collipeumo peak, lined them up, and opened fire. The killers then threw their bodies into the canal below. But Bustos survived.

Orlando Pereira’s sister Mónica was at the scene of the executions in October 2015, when Alejandro Bustos assisted in a court-ordered reconstruction of the crimes.

“Alejandro said that when [the killers] shot them, my brother [Orlando] fell on top of him and covered him with blood,” she said. That allowed Bustos to play dead. His survival made it possible for his neighbors to find their loved ones two days later—and eventually seek justice. But he would also provide a glimpse of the forces behind the violence that had descended on Paine.

Identifying the Killers of Paine

Between mid-September and November 1973, Paine’s civilians collaborated with members of the military and police to forcibly disappear or execute at least 70 people, many of whom remain disappeared. Paine holds the record for highest number of victims in proportion to number of inhabitants during the junta years. More than 3,000 people were killed or disappeared nationwide during the dictatorship. The majority of victims in Paine were campesinos and beneficiaries of the land reform.

Before the reform, 80 percent of Chile’s land had been tied up in just 7.5 percent of properties. About 70 percent of campesino families earned less than $100 annually. The reform of Allende’s government aimed to incorporate campesinos into political and economic life, redistributing land under the motto "la tierra es para el que la trabaja" or "land to the tiller." By 1973, the program had brought an end to the latifundio estates, and as one article put it, “[liberated] the peasants from the power of the landed class that had dominated rural Chile for three centuries.” After the coup, the program became a target of the regime and its allies.

“The land reform was the most hated policy of [former presidents] Frei and Allende,” said Brian Loveman, a professor emeritus of political science and author of Chile: The Legacy of Hispanic Capitalism. “The early repression was intended to create terror within the land reform sector—and it did,” he said. “The local ex-landowners and local officials settled personal conflicts and carried out vengeance as part of the early stages of the coup.”

The Tagle family, for example, had owned the Paula Jaraquemada asentamiento as a latifundio estate, according to Javier Rebolledo’s book on the Paine crimes, A la sombra de los cuervos. At least two members of that family were accused of involvement in the violence, including the Collipeumo massacre.

Elite former landowners worked with Carabineros and military personnel to “identify ‘activists' in the land reform process,” as Loveman explained. And in a 2017 report, human rights lawyer Nelson Caucoto Pereira noted that “the lists of detainees were always drawn up by the members of that elite, by the civilians of Paine.”

Despite amnesty laws that protected the killers for decades, Alejandro Bustos and Orlando Pereira’s widow, Nancy Moya Castillo, publicly accused Carabineros and several civilians—“many of them locals and well known in Paine”—of torturing and murdering the four men at Collipeumo as early as July 1990, four months after the end of the dictatorship.

Bustos’s testimony as the sole survivor of the massacre was key in the 2017 conviction of Francisco Luzoro Montenegro. Luzoro was the first civilian to be convicted over Pinochet-era violence. But as Rebolledo, who specializes in the investigation of systemic human rights violations in Chile, wrote, Bustos testified in 2003 that there were other civilians present during his detention, including a young Christian Kast.

Kast Family Denials and the Republicano’s Rise

Christian Kast is part of a far-right dynasty. Bustos said he saw him at a barbecue at the Carabineros station, and Christian has admitted to hearing mention of a man who would later be disappeared. His father Michael was a member of Paine’s elite and a former member of Germany’s Nazi Party who fled denazification after the war. His son Miguel studied at the University of Chicago; Pinochet appointed him as labor minister and later, president of the Central Bank. Miguel was part of the so-called Chicago Boys, a group of Chilean economists who shaped dictatorship-era economic policies and imposed neoliberal reforms. But in recent years, Christian and Miguel's younger brother has clawed his way into the spotlight as the nation’s leading far-right figure.

José Antonio Kast was seven years old in 1973, when his family was first accused of terrorizing their neighbors. Kast, who leads the right-wing Republicano Party, has not distanced himself from their suspected crimes. But that has not stopped him from gaining prominence.

In 1988, as the majority of Chileans voted to remove Pinochet and return to democracy—Kast campaigned for the general to remain in power for eight more years. When Kast ran for president in 2017, he garnered less than 8 percent of the vote on a platform that included immediate pardons for imprisoned former members of the dictatorship.

“If Pinochet were alive, he would have voted for me,” Kast said that year.

By 2021 though, Kast had gained ground at the polls, securing a spot in the presidential runoff against leftist Gabriel Boric. Kast’s popularity was built on his commitment to “family values.” He stands against marriage equality, abortion, and Chile’s participation in the UN Human Rights Council and is known for drumming up anti-migrant hatred against people from Haiti and Venezuela. Kast and his Republicanos have also proposed closing the Ministry of Women and Gender Equality and increasing prison construction.

While Boric defeated Kast in the runoff, the influence of the hard right is growing across the Americas. Kast has been widely compared to Brazil’s far-right former president Jair Bolsonaro. In neighboring Argentina, far-right figure Javier Milei, an admirer of Donald Trump, is leading the polls ahead of a vote next month. And in Mexico, Eduardo Verástegui, director of Sound of Freedom—a film many have linked to the far-right QAnon conspiracy theory—has filed to run in upcoming presidential elections. In El Salvador, President Nayib Bukele has been accused of “eroding democratic freedoms and rights” with his war on gangs.

On May 7, Kast’s Republicano party won a majority in a vote for a committee to rewrite the dictatorship-era constitution—though as AP News reported, the party “has long said it opposes a new charter.” As of August 6, polls showed Kast was one of the top two contenders for the 2025 presidential elections. Political scientist Loveman said a Republicano victory could have consequences for those still seeking justice.

“A future right-wing government…might reduce prison sentences for some of the convicted military officers and civilians, who are in their 70s and 80s, at least. Such a government might also influence the still-open judicial investigations [into dictatorship-era crimes]—and there are many of these,” he said.

But for Susana Capriles, director of Radio la Voz del Paine, a community radio station focused on platforming voices against injustice, whether Chile elects a Kast government will depend on how people organize against it. “The advance of the Republicanos in this most recent vote is a show of the weakness of the Left, of the weakness of progressive proposals in respect to the construction of an autonomous, independent, and collective project, formed from the base, from the real needs of the population,” said Capriles.

Kast has deflected and denied accusations against his family, from his father’s past in the Third Reich to accusations against them in Paine. Rebolledo addressed this in a 2022 interview on Kast. “[He] cannot say ‘my family didn’t have anything to do with this,’ that they didn’t do patrols, that they didn’t support repression, that they didn’t lend their vehicles or that one of his family members wasn’t identified in a shooting,” said Rebolledo. He continued: “He can’t say that. And that is what he has said, that there is nothing judicial against his family, but he doesn’t say the reasons.”

Those “reasons” are simple: Kast’s father Michael died while still under investigation. According to Rebolledo’s book, “many knew that Michael Kast provided food to the carabineros, as well as a red truck and a driver, in which it is possible campesinos were detained.” Christian was not charged as he was 17 in 1973.

That a member of the Kast clan may one day lead Chile is a chilling prospect. According to the United Nations, forced disappearances are more than kidnapping and murder: they constitute crimes against humanity.

Searching for Chile’s Disappeared

Last month, ahead of the 50th anniversary of Chile's 1973 coup, President Boric announced a national search plan to locate the more than 1,000 people who are still disappeared. Capriles of Radio la Voz del Paine, which has been a part of commemorating the anniversary of the coup, hopes the plan materializes into something concrete, not just “a rhetorical good faith proposal.”

“There’s an old saying that hope is the last thing to be lost,” she said. “But it’s difficult to think about true justice in respect to human rights here in Chile, because it is marked by a profound denialism and an important pact of silence that has prevented true justice from being achieved.”

Also in August, the United States declassified a document showing Washington had knowledge of the 1973 coup before it happened. Capriles called on people in the United States to become aware of how their government intervened in Chile—and to hold them accountable for it. She said, “I think it is important that from within that same country, people denounce and demand political responsibility regarding the tremendous interventionism the United States had in the future of our political history.”

As Capriles said, the families of the disappeared and executed understand that “memory is also a front of resistance.” And despite slim prospects for justice and the denialism of Chile’s Right—even as it gains power 50 years after Pinochet’s coup—Paine has not forgotten its dead.

Nyki Duda is a Chicago-based writer, editor, and researcher.