Leer este artículo en español.

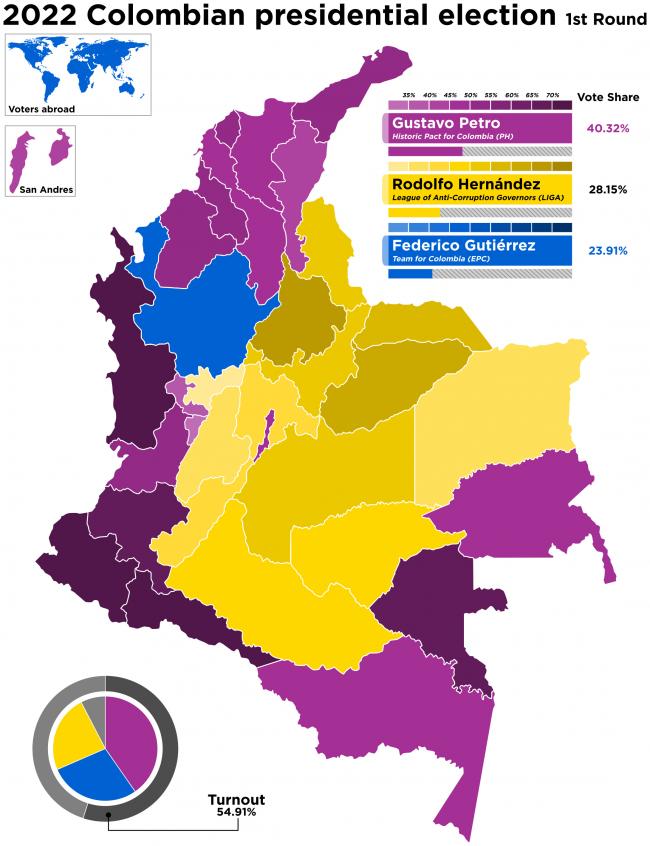

Colombia’s first round presidential election resulted in a historic defeat for the country’s hegemonic bloc. With 40.9 percent of the vote, support for leftist Gustavo Petro and his running mate Francia Márquez represents the most important advance for the Colombian Left in its history. For the first time, the Left will compete in the second round, scheduled for June 19, with a real possibility of winning.

Federico “Fico” Gutiérrez, the conservative candidate representing the establishment, the traditional parties, the mainstream media, and the ideology of Uribismo, secured less than a quarter of the vote. With 23 percent, he failed to make it to the runoff.

This result in itself represents a profound change in Colombia, where Uribismo has remained iron-clad for more than 20 years.

Yet Petro’s definitive victory in the second round is not guaranteed. The second-place candidate, Rodolfo Hernández, who finished somewhat surprisingly with 28.1 percent, renders the outlook more complicated for the Left than if Fico, a traditional conservative, had made it to the second round.

Hernández, a politically incorrect populist, entered the race as a kind of outsider. Launched as an anti-establishment choice, he now positions himself as the ant-Petro candidate who can scoop up support from Fico voters with relative ease to triumph in the runoff.

If the scenario were reversed, however, Hernández’s votes would have been more difficult to transfer to Fico, due to the anti-establishment sentiments of Hernández’s supporters.

Hernández’s problem now is that a good portion of the votes he obtained in the first round were due to his anti-status-quo position, and it remains to be seen how the voters that supported him in the first round will cast their ballots in the runoff when conservative institutions through their weight behind him, as Fico did immediately after the results came out. Will this betray Hernández’s supporters and sink his candidacy, or give him to necessary votes to propel him to the top office?

This is the great unknown emerging out of the vote on May 29.

For Petro’s part, his speech after the results came out did not clarify what his strategy will be in facing Hernández in the second round, his camp’s less-desired scenario. Now, his messaging will have to shift, because Hernández’s “anti-Petrismo” is no longer representative of Uribismo, to which Petro has positioned himself as an alternative. He will have to confront an opponent who does not yet have an established script.

As a result, Petro and Márquez cannot yet claim victory, and Uribismo may take advantage of the situation to try to orchestrate his defeat. Indeed, Uribismo is better positioned to achieve this goal by supporting the outsider than with its own candidate in the race.

Understanding Uribismo

Uribismo—embodied by the policies of former president Álvaro Uribe, who governed from 2002 to 2010—is seen from the left as a repressive conglomeration, associated with paramilitarism and narcotrafficking. But this only shows one side of the coin. We must consider that, regardless of the violent and political forms of cooptation it employs, this movement has dominated the country for two decades and represents a colossal electoral, political, and military phenomenon. That reality of Uribismo must be understood—especially if the goal is to overcome it.

Uribismo has been propped up by a system of dominant alliances that cater to the United States and sustained by the perpetuation of internal armed conflict that legitimizes a brutal repressive order. It is, of course, also sustained by the export of cocaine.

Colombia became the United States’ main Latin American ally, its “beachhead” in the region. This came amid the Colombian government’s fight against guerrilla groups that controlled vast areas of the country, the rise of Chavismo in Venezuela, and the radicalization of various currents of the Left in Latin America. Uribe’s government welcomed U.S. military bases, advisers, troops, and tutelage into its strategic position to safeguard what Washington has long considered its backyard: Latin America, and specifically the juncture between South and Central America and between the Caribbean and the Pacific. This strategic site is now in serious jeopardy for Washington—not because of guerrilla victory as was the case in decades past, but because of the results of a peaceful, democratic, electoral process.

Since the 2016 peace accords with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), Uribismo has ebbed. Sparks of political conflict shifted from sharply ideological battles toward more social demands, unsettling the traditional configuration of politics as a military and rural form of combat. Despite triumphing in the 2016 plebiscite on the peace deal, in which the “no” vote pushed by Uribe’s camp was victorious, and winning the 2018 elections with current president Iván Duque, Uribismo is clearly under threat. Duque’s term in office can be seen as representing this decline amid an internal crisis within Uribismo. On the one hand, the oligarchs became unwilling to continue being bogged down by the logic of war that long engulfed Colombia. On the other, liberal institutions also began to purge themselves of Uribista influence.

A defining fissure was already emerging during former president Juan Manuel Santos’s administration. In office from 2010 to 2018, Santos proposed “moderation” in response to the armed conflict, even though he had been a prominent military actor as Uribe’s defense minister. As a representative of the traditional oligarchy, Santos sought to “clean up” the violent image of the Colombian state with a degree of success—and a Nobel prize. This was without Uribe’s consent, who sought to prolong the war.

Despite leaving a trail of persecution, breaches, and murders of ex-guerrilla leaders, the 2016 peace accords allowed sociopolitical conflict to shift from the remote countryside into urban centers and peripheries close to political power. Protests, cacerolazos, strikes, and pickets replaced armed insurrection and its military responses.

After having won the last five presidential elections, Uribismo’s decline became clear with its loss of the October 2019 regional elections

Under Duque’s government since 2018, internal resentments have bubbled within Uribismo. When Duque released his ill-fated tax reform, Uribe made an “anguished plea,” as he called it, for the government to pursue other avenues. Duque did not listen. While this did not amount to a rupture, it did signal the slackness within the movement.

Meanwhile, Colombia’s “social explosion” was underway, changing the image of a “stable” country “on the rise” to one of an ungovernable and fragmented state.

And in the March 2022 legislative elections, Uribe’s Centro Democrático fell from being the most powerful movement in Congress to being a minority.

With Uribismo deflated, Petro entered the fray with a moderate proposal linked to the social movements that confronted Uribismo during and in the aftermath of the armed conflict. His vice-presidential pick solidified an unconventional but very committed leftist proposal with popular demands and a political project that, more than liberal or progressive, represents the new Left.

Wins and Losses for Uribismo?

Speaking of Uribismo’s defeat in the first round is a statement that must be qualified. It could be said that Uribismo, a historical phenomenon, has opted in this instance for “self-dissolution” in order to “infiltrate” a political current that is as anti-Uribista as it is de-ideologized and pragmatic.

But Uribismo’s historical objective is to displace the Colombian Left. This has been its purpose since its genesis, and its goal may again be achieved in this election cycle if it disintegrates in order to free the “anti-Petrista” candidate from its beleaguered legacy.

So is it the end of Uribismo?

Ociel Alí López is a political analyst, professor at the Universidad Central de Venezuela, and contributor to various Venezuelan, Latin American, and European outlets. His book Dale más Gasolina won the municipal literature award in social research.