“This is contamination, Señor Presidente.” Guillermo D.Christy directly addresses Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador as he holds a slab of dissolving concrete up to his handheld camera.

Dark and damp and deep, the Ak’Tun cave system hides below the surface of the jungle. Thousands of calcified fangs drape down from the ceiling toward the uneven ground where, on the other side of the waist-high pool of murky water where we stand, four imposing steel pillars have been inserted into the cave from above. “They are contaminating the aquifer and this is going to affect the region’s water supply,” D.Christy broadcasts to the outgoing head of state.

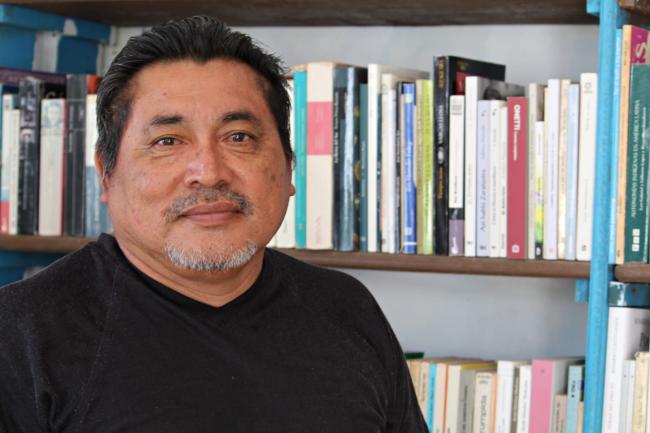

D.Christy is a water consultant who regularly volunteers for the environmentalist group Cenotes Urbanos, founded in 2018 to promote the preservation of the region’s unique subterranean environment. This particular cave is one of thousands across the Yucatán Peninsula, on Mexico’s southeastern edge, home to the largest system of underground rivers in the world. Most famous for its freshwater cenotes popular with tourists, this vast interconnected network also forms the Great Mayan Aquifer, the source of drinking water for roughly five million Mexicans.

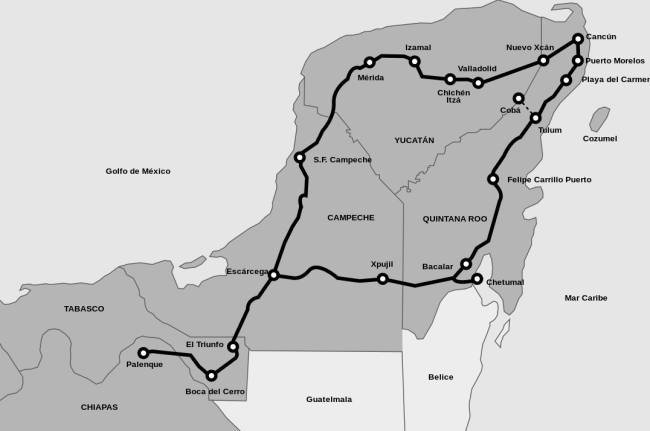

In September 2018, newly elected President López Obrador (known as AMLO) announced his plans to begin construction of the so-called Tren Maya. Named after the Indigenous people of the region, this new tourist train will run over 900 miles (1500 km), circumnavigating the peninsula and connecting the Maya Riviera’s popular beachfront destinations with the rich biodiversity and ancient archaeological ruins of the interior. Participating in a traditional Maya ceremony to ask permission for his new megaproject, AMLO promised the train would bring jobs and development to pay the Mexican state’s debt to its historically neglected southeast: “It is above all an act of justice” proclaimed AMLO, who hails from the nearby state of Tabasco.

Though partially inaugurated in December 2023—with lines currently running from Cancún to Playa del Carmen and down to Palenque in the interior state of Chiapas—the four steel pillars D.Christy has brought me down to see form part of the project’s most controversial and as yet unfinished route. “Section Five,” connecting Playa del Carmen with Tulum, was originally conceived to run alongside the highway, but after successful lobbying from the hotel industry over concerns it would disrupt business, the government agreed to move construction. The new route will cut through 41 miles (67 km) of Latin America’s second largest jungle, directly on top of the region’s most dense concentration of caves and cenotes.

The government began construction “without a single study on the impact of these pillars we are seeing,” according to D.Christy. In February, a federal court in Yucatán ordered the immediate suspension of all construction on section five until the government can deliver scientific studies demonstrating the legally-mandated environmental impact conditions, set out under the government’s 2022 authorization of the line, have been met. The fear is that constructing the train directly on top of the aquifer’s fragile karst soil foundations will not only increase contamination—something AMLO has acknowledged is already occurring—but also risk a collapse of the earth. Despite this latest legal ruling, however, construction has only accelerated.

From the outset, experts have raised alarm. In July 2020, a group of 85 academics signed a petition calling on the government to halt construction plans, considering the train an environmental threat “on a planetary scale.” Rodrigo Patiño Diaz from the group Articulación Yucatán, who signed the original petition, warns of the project’s potentially devastating impacts on the aquifer, already under intense pressure from urbanization. “When the project was proposed, the system was already deteriorating… We are facing a serious problem that could lead to the collapse of the water-system in the entire region.”

“It’s Pure Politics”

Not everyone is contesting the new megaproject. “The people are happy because they didn’t have sources of employment,” I was told by Andrés, a former construction worker turned taxi driver in Playa del Carmen, a thriving tourist hotspot abutting the Ak’Tun cave system. “I know many people who lost their jobs in the construction industry, now they have work again.”

Andrés notes that while for now there’s only a passenger train, the new government has promised to add a cargo train to move products, “which will bring more jobs for the people.”

The new government Andrés is referring to is that of Claudia Sheinbaum, AMLO’s chosen successor to lead the Morena party to victory in the June 2 presidential election. Sheinbaum has emphasized the government’s plans to build out the train’s cargo-carrying capacity—including proposals to eventually connect it with the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, another AMLO megaproject, that is being hailed as Mexico’s alternative to the Panama Canal.

When I asked Andrés about the environmental concerns over the train, he dismissed them as part of a conspiracy to undermine the government. “There are economic interests that manipulate the people to not construct the train. It’s pure politics.” Indeed, Andrés’ views seem to closely mirror the lines coming from the governing party.

Boarding the new train for the very first time from Cancún station, I was struck by a bolt of journalistic luck. Sitting in the carriage ahead of me, surrounded by press, was the presumptive next president of Mexico, Claudia Sheinbaum. I asked Sheinbaum, herself a climate scientist, about the environmental concerns surrounding the train.

“All projects have impacts” she said. “The issue is if there is mitigation of this environmental impact… And in this case, yes, this was done.”

“Historically this area, particularly in the zone of Cancún and the Maya Riviera, has experienced a very severe environmental impact with the large hotels,” Sheinbaum told me. “The environmentalists of today never said anything about these impacts. And now they are talking about the impact of the Maya Train, which has a lot to do with politics and little to do with knowledge.”

Develop First, Ask Questions Later

The railway is not entirely new to Yucatán. During the 19th century, private companies laid tracks across the peninsula to aid the transportation of henequen fibre, used to manufacture rope, as the region’s primary export crop. This “Green Gold” was exploited in the region for over 200 years, harvested by Indigenous peons under a brutal system of de facto slavery on local haciendas. At the turn of the century, however, the invention of plastic effectively stopped the Yucatán henequen trade in its tracks. The jungle has since reclaimed many of the old plantations. Over time, the trains that used to transport goods and people around the peninsula slowly faded into disuse.

The story of the railway in Mexico, a tale of rapid expansion and steady decline, occupies a unique place in the political imaginary of the nation: at once a promise of progress and a reminder of past failures. It is little wonder therefore that AMLO has been able to sell his signature project to the public as a symbol of national revival.

Coral Mota Green is a member of the Consejo Regional Indígena y Popular de Xpujil (Regional Indigenous and Popular Council of Xpujil), which in 2021 launched a legal challenge against the government’s plans to build the Tren Maya through the Calakmul biosphere. Mota Green acknowledges the president’s broad popularity, but has been disturbed by the lack of proper consultation in local communities to approve the train.

“It was important that the president came from the people… so when López Obrador arrived people began to express their demands. They asked for roads, healthcare, education, water, and so López Obrador said ‘Yes, the train will bring all of this, so you are all going to accept the train.’”

In 2019, a referendum held by AMLO to approve the train passed with around 90 percent of the vote. But with less than one percent turnout, and UN observers subsequently criticizing the government’s one-sided consultation of Indigenous assemblies, the Mexico Office for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights concluded that the process had not complied with international standards. Despite this, AMLO declared the vote an emphatic endorsement of his project and proceeded with construction.

Over his storied political career, AMLO has cultivated a “man of the people” image among ordinary Mexicans through a blend of provincial charm and uncompromising rhetoric against the forces of neoliberalism. An enigmatic political figure, blending shades of pink-tide leftism with traditional Mexican populism, he now consistently polls as one of the world’s most popular heads of state.

AMLO’s sexenio has undoubtedly scored significant wins for working people, including the largest minimum-wage raise in 40 years, and has decisively shifted Mexican politics to the left. This has all been achieved while attracting high levels of foreign investment as Mexico undergoes something of a manufacturing boom, driven in part by AMLO’s developmental model of state-led infrastructure investment.

But questions remain over the effects such a model is having on Mexican democracy and its citizens. Under AMLO’s watch, the Army has been granted oversight of the Tren Maya’s construction and operation and now controls several key airports in the country—leading to what many have cautioned is a dangerous militarization of Mexican public life. In fact, the many legal challenges brought against the project by environmentalists and Indigenous groups have been successfully swatted away by AMLO’s presidential decree ruling the train a matter of “national security,” despite the Supreme Court declaring this unconstitutional.

Riding a wave of popularity, it appears that AMLO has pursued a strategy of develop first, ask questions later. Whether such a strategy is viable in an era of climate catastrophe is under severe scrutiny. As is often the case, the people caught on the fault lines of such ambitious nation-building projects are the voiceless and historically marginalized. In this case, the Indigenous people of the peninsula.

A Territorial Reconfiguration of the Southeast

The Yucatán peninsula holds a huge “biocultural importance,” explains Jazmín Sánchez Arceo from Articulación Yucatán. The immense biodiversity of the region is “sustained and preserved by the ways of life and special relationship with the Indigenous peoples, in particular the Maya people.” The train, and other megaprojects like it, from agroindustry to energy parks, form part of an extractivist model of development that is driving what Sánchez Arceo considers a wider “territorial reconfiguration” of the southeast. This includes the acceleration of the once gradual retreat of ejido territory in the region— the system of common land use that emerged after the Mexican Revolution. Indeed, after initially claiming only federal territory would be used for the train, the government has resorted to expropriating numerous ejidos.

Coupled with the anticipated surge in real-estate speculation, it appears the Tren Maya is only deepening dynamics of territorial reconfiguration that are being exported from the proving-grounds of Cancún throughout the rest of the peninsula. The specter of Cancún, an artificial tourist megalopolis that serves as a cautionary tale for what unchecked development can bring, troubles many who feel unable to slow down, let alone halt, the pace of change. “These large projects are always conceived from above… the capacity for agency in the local populations is very low,” Sánchez Arceo laments.

Resisting the Horse of Fire

Pedro Uc Be is a prominent Maya poet who helped found the Múuch Xíinbal Assembly of Defenders of the Maya Territory. Uc Be grew up as a monolingual Yucatec Maya speaker and began learning Spanish at age 18; the only book he had to work from was a single copy of the Bible. As many men of humble means and intellectual talent before him, he trained to be a priest and was then exposed to liberation theology—working alongside the famous Bishop Samuel Ruiz during the time of the Zapatista Revolution. Now, after renouncing the Christian church to return to his ancestral roots, he dedicates himself to writing poetry and defending Indigenous territory.

Welcoming me into his home in the sleepy heartland town of Buctzotz, Uc Be told me how the train represents “the project that integrates all other projects” in a wider trend of division and displacement on the peninsula. Uc Be is unequivocal in his condemnation of AMLO’s dealings with local communities and accuses the president of manipulating the people in order to push through his flagship project. “In this picture the Mayas don’t appear. There is no possibility to benefit us despite all the propaganda the government has made… it is all a perverse discourse, as crude and cynical as I have seen. This government has crushed all of our hopes as Indigenous people.”

When asked what alternative model of development he would like to see on the peninsula, Uc Be responded as many others had when presented with the same question: autonomy. “What the government should do is respect the will of the people to organize and make their own decisions—in coordination with, not subordination to—the state.”

The Mayan word for train, Xchimes k’aak’, literally translates to a horse of fire, Uc Be explains. “When the Maya see something new, they name it based on their experience and the understanding they have, following a cultural logic. ”Upon seeing the first train in Yucatán, the Maya likened it to the horse: something that runs fast and was at one time unknown to the Indigenous people, brought over by their colonizers.

“The horse for the Maya is a suspicious, untrustworthy, figure. The horse is an adversary; but it is an adversary obliged to serve the true adversary... a useful fool.”

Jack Phillips is an independent reporter based in London, England. He is also soon to be enrolling in graduate study at UCL’s Institute of the Americas in September 2024.