Lee este artículo en español.

Translation by Liza Schmidt.

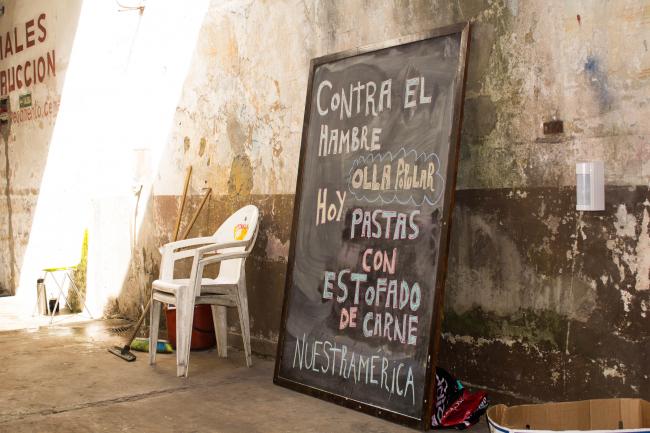

On the sidewalk in front of an illegal hotel in Constitución, one of the Buenos Aires neighborhoods hit hardest by social inequality, neighbors add whatever they have available to a giant pot cooking on an improvised fire. Suleika offers potatoes and rice, Mariela vegetables, Juan Pablo a chicken, and Daniela a few kilos of food provided by the Migrant Workers and Refugee Front of the political group Nuestramérica Movimiento Popular. They are cooking guiso, a stew made from literally anything that is available. Everything is mixed together in the pot with a bit of water to cook. A sign next to the fire reads “Olla Migrante” (migrant pot).

“This project was born as a tool to start creating a stronger connection between migrant neighbors,” explains Daniela Trujillo, an activist in the Nuestramérica Movimiento Popular, a political organization that provides basic necessities and demands that the state take responsibility for the needs of the people. She is referring to the communal meals offered in hotels for poor migrants. The meals are organized to feed people and bring them together. “By chatting in line while they wait for their lunch, it became clear that people didn’t just need food, but also help dealing with bad housing conditions and finding work without immigration papers. Many are misinformed about the regularization of migrants, among other problems,” she says.

They are cooking in the street to increase awareness about the area’s primary issue: the inhumane conditions of the illegal hotels where people who come to Argentina without money or contacts end up living. The spaces are unclean and unsafe and do not offer any formal leases, leaving tenants at the mercy of the owners who evict entire families when they fall behind on rent. These family hotels, as they are called, mainly house poor refugees who came to Argentina in search of a better life and are forced to accept the cheapest option they can find.

That these living conditions exist is evidence of the deadly shortcomings of our cities.

In a system of death like capitalism, social inequalities escalate each year and leave many living in misery. Collective organizing and activism is one form of resistance against that social determinism. Many experiences come together as part of the stew, including those of Indigenous people reclaiming their land and people living in the street without their human right to a proper home. These mix with the demands of women who reject the gendered responsibilities of cooking and cleaning to instead participate in politics and the call from migrants to remember that xenophobia is backed by state laws. All these historic grievances form the recipe.

Supporting Vulnerable Communities

In the early 2000s, thousands of people in Argentina were sleeping in the street or searching the trash for scraps of food as a result of decades of neoliberal politics. The piquetero movements were composed of the many left unemployed by the crisis that exploded in 2001. Despite a hopeless situation, they created a system of resistance and solidarity that has grown over the years into organizations that push for political change that reaffirms and secures long-denied rights.

These movements strengthened their protest symbols in the last 20 years: road blockades, chants, tire burning, pot-banging, and community pots. Each of these symbols has a strategic function.

In the neighborhood, at one of these migrant hotels where the olla popular sizzles, cumbia plays loudly from a speaker pointed down the short street, while plates are passed from hand to hand. Some people eat standing so they don’t lose a minute of dancing, others are seated in chairs or on the ground, chatting between mouthfuls, while others interrupt constantly to ask that everyone respect social distancing to keep everyone safe. When they finish lunch, those who were serving the food help the diners with whatever they need—migratory processes, evictions, or any other issue they’re facing. They also share more about their organizations and—why not?—discuss politics. After all, the postprandial moment is the most important one in the history of social movements: strikes, revolutions, marches, all brew in the moment when digestion begins.

The cooks finish thanking everyone who came to eat, and everyone applauds because they know that their gratitude is from the heart. As people dismantle the scene and clean the pot, others join their comrades from the communal political space Galpón 14 de Octubre. For years this space has acted as a site of support, advice, and action around the neighborhood’s problems.

Covid-19 and the resulting lockdowns made things even more difficult for people who work informally in the streets or for those who don’t have the means to take health precautions, so the existence of these community spaces became even more important. For people in vulnerable social situations, getting together and creating collective support has been essential for joining forces, sharing information, gathering their courage, and pressuring the powers that be to give weight to their human rights.

“While the primary goals that we are pursuing as migrant and refugee activists are migratory regulations, adequate shelter, and dignified work,” Trujillo said, “the pandemic has forced us to address basic human rights that are being violated in the middle of this health crisis. Cooking in the street is a way to generate attention about the situation in migrant hotels: living precariously, in overcrowded and unsanitary spaces.”

When the mandatory social isolation began in March 2020, the activists from Galpón 14 de Octubre had to fully redirect their daily work towards delivering at least 600 plates of food per work and dealing with neighborhood emergencies.

The work of feeding so many people can only be achieved with strong will and absolute dedication from those who plan the menu, chop vegetables, and create and publicize donation campaigns that fund this work. For these workers, it is a responsibility to fight for a world where no one lacks food. This lack of food is not accidental, it has a structural counterface that permits its existence, as Movimiento Popular Nuestramérica member Facundo Cifelli Rega explains, “We realized that, although there was a real need and a food crisis, behind that was an even larger crisis, and that’s the lack of jobs.”

Out of the Labor Crisis, Cooperativism

Many of the people who lend a hand to cook lost their jobs during the lockdown, and while they chopped vegetables, they began brainstorming a solution to this problem. It’s not news that the formal job market does not accommodate all the people who need work. The first option that they came up with was to create work cooperatives according to their skills: some people knew how to cook, others to sew and mend clothes, others how to make artisanal beer. They created various cooperatives—one for textiles, one for food, and one for making beer—in a work scheme that employed new logics and forms of production outside of capitalism’s exploitation.

“Through the work cooperatives—without any models—they established a new type of relationship between the workers with more democratic and horizontal structures, both in the work and leadership roles,” said Cifelli Rega. “From this you can see how, within work, there are other human objectives beyond individual accumulation of capital and profit without scruples.”

Cooperativism is an alternative to the “formal economy,” a labor system that excludes millions of people based on race, gender, or migratory status. For them, a stable job is a promise of wellbeing that is unattainable, because the reality is that most poor people are born poor and die poor. Accepting that the formal market is exclusive and that many people are never part of it is to speak of the elephant in the room and begin to give shape to a worker’s identity that forms the popular economy, with its diverse rules and cultural representations. There, the community pot is the star.

“As a Colombian migrant, internalizing Argentina’s history and struggles, I always knew that the fight was brewing in the streets,” says Trujillo. For her, sometimes the bureaucratic timelines are useless when problems are urgent and there is no institutional response. She adds that “people have no other choice than to demonstrate their anger. It’s a way to say, ‘I am here and don’t mess with me.’”

“Here the community pot is an important symbol of struggle and resistance,” says Cifelli Rega. “Cooking is an act of love.”

The community pot has a thousand meanings for those who fight for better living conditions, and holds particular importance for demonstrating how hunger can be addressed with what is at hand: organization and popular empowerment. After all, who can plan future revolutions on an empty stomach?

Virginia Tognola writes about politics, culture, humanitarianism and activism in the Movimiendo Popular Nuestramérica. She has published work in International Progressive, ROAR Magazine, New Internationalist y NACLA about the social issues and the fight for human rights in the region.