Downtown Juárez is an extraordinary book that indeed captures “the underlying narrative of a misunderstood border community,” as Alfredo Corchado, Mexico border correspondent for the Dallas Morning News, states. The main characters in the stories it tells are many times misjudged. A sex worker interviewed for the book notes as much when explaining the nature of her job, saying: “many people classify us as a prostitute but they don’t know that we come here for economic reasons.” Against that reality, this book represents an important effort to document such voices, enabling them to be more widely heard.

The author of Downtown Juárez is Howard Campbell, a professor of cultural anthropology at the University of Texas at El Paso, who knows the city extremely well. In 2009, he wrote Drug War Zone: Frontline Dispatches from the Streets of El Paso and Juárez, another excellent book related to the central U.S.-Mexico border region. By telling the tragic tales of people who live in very dire conditions—and perform activities that are not ideal—in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Campbell seeks to offer a general explanation of the intense violence that takes place every day in the central part of this very complex border city.

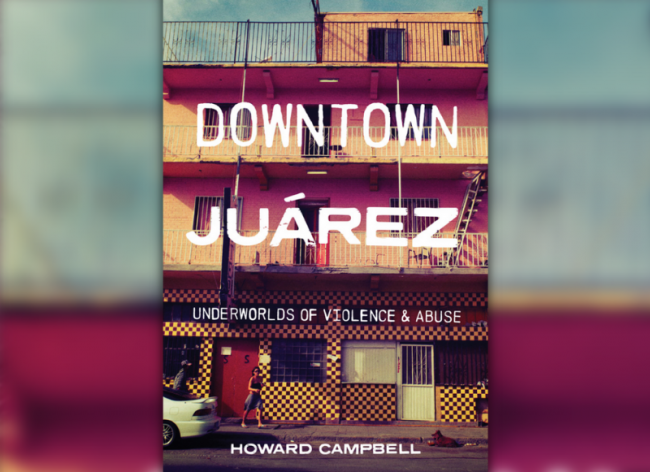

He talked to people in very dangerous parts of downtown Juárez in an effort to understand their reality. This is a courageous task; Campbell was robbed and bitten in his quest to discover the social, economic, political, and human dynamics of this violent city and their effect on its inhabitants. Throughout most of the 17 chapters in the book, he explains the city’s violence through the testimonies of its survivors. This text and its stories are the result of brave, humane, and exemplary ethnographic work that depicts the “underworlds of violence and abuse.” Campbell concludes by analyzing what he defines as “synergistic violence” and explaining the cycle of victimization on the border.

The first five chapters of the book provide key context for understanding a region where nearly 12,000 people died in just one decade between 2010 and 2020. These chapters describe the conditions that generate violence and elucidate how this phenomenon is normalized in a border context. In this first section, Campbell explains the transborder dynamics that affect life in the city, as well as how power is concentrated in a very unequal region and how economic exchange and transnational companies (maquiladoras, essentially) determine socioeconomic relations. To illustrate his main arguments, Campbell first describes the situation of violence, crime, and abuse in downtown Juárez—particularly in Colonia Bellavista and Avenida Juárez—both in the past and today.

The rest of the chapters tell the city’s story through the testimonies of various characters, including former drug traffickers/dealers, gang members, human traffickers, sex workers, corrupt local policemen, and expatriates. Each of these characters find themselves trying to subsist while coping with the violent reality of Juárez. In order to survive, feed themselves, provide for their families, or even enjoy life in very precarious situations, people often turn to crime. The lack of economic opportunities together with ever stricter U.S. security and immigration policies explain the cycle of violence in this border city. As part of this cycle, illicit activities—including murder, drug sales, and prostitution—are, according to Campbell, “the direct result of historical socioeconomic marginalization and the reproduction of poverty, injustice, and suffering that produces a naturalization of criminality and mayhem.”

The book highlights the inequalities that are very visible in the city and shows how the lack of employment opportunities pushes people to commit crimes. Through extensive ethnographic work, Campbell explains how an economic system that he defines as “neoliberal” has also led to high levels of violence in Ciudad Juárez, as it removed safety nets, furthered the use of maquiladoras, and contributed to increased undocumented migration and immigration. Overall, he explains how violence at the borderlands has been jointly created by Mexico and the United States, as well as how U.S. immigration policy has contributed to the current circumstances. Campbell sees the international bridge connecting El Paso and Juárez as a symbolic structure that physically embodies an unequal and contradictory relationship between two neighboring countries.

In the end, the dynamics of such a relationship means the creation of wealth for the United States and violence for Mexico. These inequalities and contradictions are, according to Campbell, “created by the maquiladora industry, U.S. immigration and drug policy, and the extreme social stratification in Mexico.” These “areas of sharply defined inequality” are also “sustained and worsened by a corrupt political system and essentially criminal police forces.” In addition to high levels of drug addition, he adds, “ready access to U.S. weapons and the emergence of highly organized criminal groups produce an especially lethal environment.” From the text, it becomes clear how the wide availability of weapons has facilitated gang violence and other criminal activities, including sex trafficking, kidnapping, extortion, rape, arson, and others.

Campbell’s analysis also demonstrates that the main casualties of the so-called “war on drugs” were concentrated among young people and the poor. In this regard, he affirms: “Poverty, social exclusion, broken families, the experience of growing up in gang neighborhoods or cartel families, and cultural marginalization propel these youth down paths that would otherwise be unthinkable.” Women have been quite affected by this type of violence, and maquiladoras, according to some, are arguably somewhat tied to women’s oppression. Ciudad Juárez has been the epicenter of femicide, which is also a product of heightened violence and disorder.

Campbell does not simply view the impoverished young people or women of Juárez as helpless victims of a brutal, cruel, and unfair system. He instead acknowledges the role that everyone plays in perpetuating the endless cycle of violence in this border city. At the same time, he recognizes the multiple phenomena that have created the current situation. Rather than focusing on one single theory to explain Juárez’s extreme violence, Campbell says that a perfect storm of what he calls “synergistic violence” may help us to better understand this dire reality. In his words, the main components of synergistic violence causing “frequent, common, and normalized violence” are “neoliberal political, economic, and social policies; a criminal counterculture of cartels and gangs; the maquiladora economic development model; misogyny/femicide; the US and Mexican War on Drugs and its associated corruption and impunity; and US immigration policy.”

Campbell recognizes that each of these factors—operating in tandem with one another—has played a relevant role in creating an environment where crime unfortunately has become “normalized.” In this context, inhabitants of Ciudad Juárez have become desensitized to murder, theft, and rape. At the same time, police cannot be trusted, and victims of crimes often become perpetrators. Ultimately, according to Campbell, “the various viewpoints about violence” in this border town “reflect the manner in which violence gradually becomes understood and internalized, if not accepted, as an inevitable (that is natural or “normal”) element of life in the city.”

Campbell’s book and ethnographic work are extraordinary. However, I would like to conclude by saying that Juárez is much more than violence. I have been there a number of times, and I know the city and its people. The socioeconomic dynamics in this Mexican border city are indeed marred by violence and exhibit a number of contradictions. However, Ciudad Juárez also has a rich history that goes beyond the stories of narcos, margaritas, and the songs and biography of iconic singer-songwriter Juan Gabriel. Juárez is the home of very hardworking and honest people as well. Although unequal, development, art, beauty, opportunity, and growth are also part of the city’s dynamics. The tales in Downtown Juarez suggest that there is no hope in an endless cycle of violence, as there is no apparatus for change within a broken system. I believe that Howard Campbell describes extremely well one part of the reality in Ciudad Juárez, but this city—like Mexico as a whole—is so much more than violence.

As a Mexican who knows the good people of Mexico as well as the spirit of the borderlands, I still have hope. But my hope will only materialize with the creation of real economic opportunities for all the citizens of Juárez, and an effective end to the militarization of public safety or the so-called “war on drugs.” In other words, there needs to be a comprehensive change in Mexico’s economic and development model, as well as a reversal of the current hemispheric drug, trade, and security policies imposed or driven by the United States, which basically benefit its border-military-industrial complex. This seems impossible at times, but at least we have some idea of where to start the transformation of society, as well as its development model and security policies.

Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera is Associate Professor at the Schar School of Policy and Government, George Mason University. Her areas of expertise are Mexico-US relations, organized crime, immigration/migration, border security, social movements and human trafficking. She is Past President of the Association for Borderlands Studies (ABS) and is co-editor of the International Studies Perspectives journal (ISP, Oxford University Press).

The author thanks Gerardo Daniel Valladares for sharing his ideas on Downton Juárez and his perspective on the U.S.-Mexico central border, which enriched the present analysis.