Report

El Salvador, geographically the smallest and most densely populated nation in Latin America, is often described as one of the most violent countries in the region. The majority of countries in Latin America and indeed in the rest of the world have experienced a significant increase in violence and crime since the 1950s, a trend often associated with the expansion of urban spaces and social exclusion.

2000: I return to Nicaragua after being away for two years to find the capital city transformed with a new city center boasting hotels, shopping malls and multiplex cinemas. The movie Boys Don’t Cry is playing and its story of sexual transgression in the U.S. Midwest is meeting a favorable response, at least among those I talk to in the progressive community.

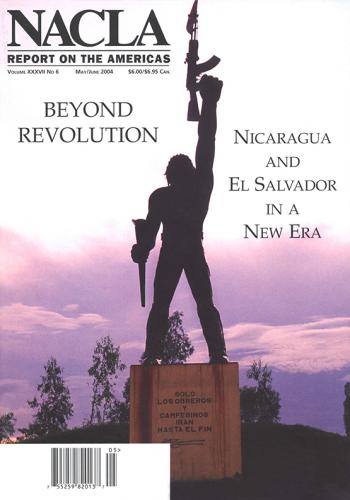

The political economies of Nicaragua and El Salvador, along with those of every other Central American country, are undergoing remarkable metamorphoses as the region is swept by globalization. A new cycle of capitalist expansion and modernization appears to be underway on the basis of a novel set of economic activities introduced in the aftermath of the 1980s wars for national liberation.

Twenty-five years ago, amid the urban insurrection against the brutal regime of Anastasio Somoza, teenagers armed with no more than pistols, hunting rifles and homemade explosives repeatedly stood their ground behind ramshackle barricades against the onslaught of the dictatorship’s U.S.-trained National Guard.

As part of its efforts to eliminate violence in all of its forms, the Bajo Lempa Coordinating Committee has spearheaded a number of initiatives designed to promote community dialogue and local development. The Committee—in conjunction with its legal arm, the Mangrove Association—pursues the diversification of agricultural production, seeks new markets for local goods and strengthens community organizing as part of its 1998 declaration of a “local peace zone” in southern El Salvador’s Bajo Lempa region.