Para leer este artículo en español, haz clic aquí.

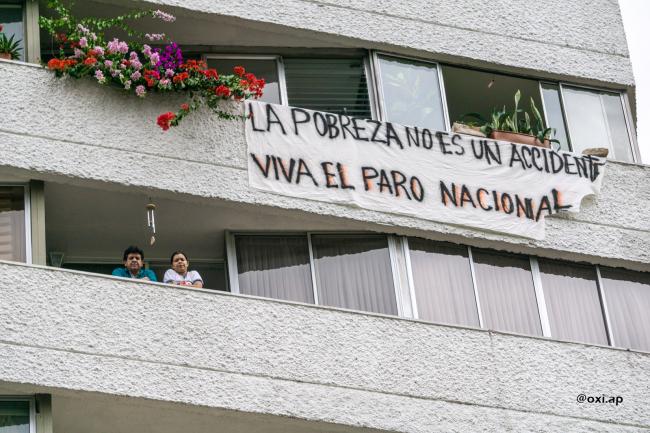

Since April 28, national strikes have consumed Colombia, showing little sign of stopping. The strikes were initially sparked by a tax reform bill, but quickly evolved into a widespread movement protesting financial inequality, poverty, widespread violence, impunity for criminals, ethnic, racial, and gender discrimination, and access to education, work, and health. Across Colombia’s major cities, there have been over 12,000 protests, the majority of which have been overwhelmingly peaceful. Despite reports that 89 percent of protests occurred without violence, the police response has been overwhelmingly repressive, inciting further demonstrations against police brutality.

The protests have divided Colombian society. On one side, the demonstrators are demanding social, economic, and political change. On the other, are the supporters of traditional institutions of power. Among those are members of Colombia’s most influential megachurches and mega-pastors, sometimes referred to as neo-pentecostals, or simply evangelicals.

Two weeks after the protests began, the Colombian evangelical megachurch Misión Carismática Internacional (MCI) live-streamed their weekly “MCI Talks” show on YouTube. The talk show featured three female pastors discussing “Our Role as Christians in These Times.” The women used examples from the Bible to discuss the value of participating in the ongoing marches and protests. They arrived at the same refrain: Colombians should not be striving for political or social change in the streets. It is change of the soul, repentance, and obedience to structures of power that will bring peace and prosperity to the faithful, they explained. One of the pastoras summed things up by saying, “I was liberated from poverty through my faith, by trusting in the Lord.”

In spaces like the MCI, economic practices, like generous tithing or even going into debt, are characterized as acts of faith. I carried out two years of ethnographic research in the MCI for my recent book, Card-Carrying Christians: Debt and the Making of Free Market Spirituality in Colombia, which examines how individual Colombians articulate faith through economic acts and the ways that religious worlds are embedded in economic logics. There is a wide diversity of evangelical Christians in Colombia, and not all evangelicals espouse the kind of prosperity theology or political engagement that I describe here. However, the current protests in Colombia and the response of many of the largest and most politically influential evangelical churches re-emphasize how certain sacralized economic practices perpetuate the social and economic conditions that have sustained the violent armed conflict in Colombia for the last 70 years.

Colombian Evangelical Response to Protests

Over the last year, Covid-19 has devastated the economy and the well-being of millions of Colombians. Since the pandemic began, hundreds of thousands have been thrown out of work and millions have fallen into poverty. Currently, two out of every five Colombians live in poverty—an increase of almost 30 percent over the last year—and over two million families cannot afford to eat three meals a day.

In April, the government proposed a tax reform bill that would raise the costs of daily essentials like eggs and chicken, give tax breaks to the wealthy elite and corporations, and further privatize the healthcare system. Although the bill was quickly withdrawn, protests have since raged across the country. In addition to financial hardship, demonstrators protest ongoing issues like impunity for state-sanctioned and paramilitary violence that has resulted in the deaths of hundreds of rights and land defenders, and a high unemployment rate—nearly 30 percent among youth. This year’s protests are a continuation of the nationwide anti-government protests that began in November 2019 in response to President Ivan Duque’s right-wing and neoliberal policy priorities and the current administration’s refusal to further implement the peace accords signed by former President Juan Manuel Santos in 2016.

Both evangelical and catholic churches in Colombia have responded to the 2021 protests in diverse ways. Some sent out their own leaders to support the “first line,” while others publicly called for the government to negotiate in good faith with the strike leaders. In a few cases churches have openly supported the strikes (if not the violence associated with some protests). Others, like the MCI, directly support the “authority” of the State and its institutions of enforcement, like the military and the police forces.

Although Colombia is notoriously one of Latin America’s strong-holds of conservative Catholicism, Colombian evangelical christianity is now growing exponentially and is overwhelmingly conservative. Over 20 percent of Colombians now identify with different expressions of non-Catholic faith, and the fastest growing sectors are evangelical and neo-pentecostal churches. While the Catholic Church in Colombia has institutionally and historically been allied with the Conservative Party, Catholic clergy have generally not run for office themselves. Evangelical pastors, on the other hand, are not only forming their own political parties, but they are winning votes for their candidates in a growing ultra-conservative, and pro-austerity swell of political theology that informs public policies. For example, MCI pastor Claudia Castellanos is the founder of Colombia’s first Christian political party, Partido Nacional Cristiano (National Christian Party). Castellanos ran for president in 1990, for mayor in Bogotá in 2000, and is currently serving her third term as Senator representing the party Cambio Radical (Radical Change) after a short stint as ambassador to Brazil in 2004. Her daughter Sara Castellanos, host of “MCI Talks,” is incumbent city councilor for Bogotá with the Liberal Party.

Adherents in the MCI are explicitly encouraged to vote according to their church leadership’s political commitments, thus guaranteeing a certain number of votes. Their votes usually oppose progressive candidates and policies that seek equal rights, progressive sex education in schools, women’s rights, sustainable peace-building, and alternative economic reforms. Instead, they focus on upholding conservative family values, pro-life positions, anti-LGBTQ+ policies, and support for neoliberal reforms. The reach of evangelical politicians is further strengthened by recent strategic unions with conservative Catholic factions.

Traditional Power Structures Align

Institutional religion and far-right politics have had a long and complex relationship throughout Colombia’s history. Recently, some of the largest and loudest evangelical churches have aligned themselves with fundamentalist factions of Catholic leadership in an unprecedented turn in Colombia’s religious spheres that has significant consequences in public arenas of political and social influence.

The alignment between conservative evangelical Colombians, the government, and other traditionalist institutions, is rooted in political practices and theologies that have sanctified neoliberal austerity measures and aspirational discourses that sustain a fundamentalist realpolitik. Many evangelicals believe that the system is divinely ordained, and the problem is individual—at the level of the soul—thus a question of internal reform. This belief supports the neoliberal mantra that poverty, inequality, corruption, and even illness are brought on by individual failings and are not the responsibility of the State. For the faithful, suffering is the result of sinful behaviour, and the way to prosperity and peace is through repentance and acquiescence to “the powers that be.”

In another “MCI Talks” episode in May, three jean jacket-clad, young, male church leaders led a discussion on “How to Be An Influence” in the current political and social moment. The hipster pastors expounded on God’s omnipotence and summed up the evangelical stance, insisting on the need to respect authority, “independently of whether or not that authority is good or bad.”

Financing Faith

There is an inextricable link between this brand of evangelical christian morality and the morality of finance capitalism in Colombia. The focus in “MCI Talks” on internal and individual strategies of self-control is central to the promise of prosperity preached by Colombia’s prosperity churches and echoed by its financial architects. The free-market system is not the problem, say these Christians, but rather the way forward. This lies in stark contrast to the protestors’ discourse of resistance, which insists that the system is not only broken, but is actively upholding a political economy of war that relies on violence to function.

This austere reality is tied directly to the late capitalist promises that “entrepreneurialism” in the informal markets, greater financialization through taking out credits from predatory lenders, and going into debt to perform aspirational prosperity are key to economic expansion and a peaceful future in Colombia. In evangelical spaces where calls for repentance and self-reform are linked to economic practices of sacrifice and indebtedness this is especially true. In the MCI, at the time of offering and tithing, credit card machines are available for the faithful to give money to God on credit when liquid finances are unavailable.

As a close collaborator at the MCI explained, “giving on faith is a sign that you trust God. Going into debt is a sign of faith.”

The aspirational conditions of these “free market spiritualities” generate, in the words of Lauren Berlant, a kind of “cruel optimism.” Faith in the market, and in the deeply theological underpinnings to the very concept of money and the “invisible hand” of the market, was fully exposed when those relying on the informal economy were told to “work from home”—an impossibility for millions that highlights the stark race and class divisions that the COVID-19 pandemic brought to light. The fact that the current economic system is actively harming the majority means that the current economic system is inherently anti-democratic and structurally violent.

The prosperity that believers at the MCI desire also prevents their liberation because their “prosperity” so often demands indebtedness. This is because, in the late modern condition of finance capitalism, it is debt that underwrites desires for prosperity, and it is debt that is the handmaiden to financialization. In this way, the cruel optimism of late modernity intersects with aspirational urges fostered through the conviction that outward signs of prosperity reveal an inner morality. This practice of indebted consumption as a strategy towards upward social and spiritual mobility becomes particularly nefarious when tied to necrofinancial orders of violence and abandonment.

Faith and Obedience vs. Resistance and Change

Under the increasing influence of evangelical churches in Colombia, aspiring, believing, and becoming are the organizing social forms of finance. This is relevant for understanding the conditions of finance capitalism and Christianity in Colombia and also on a global scale, as these social forms are being reproduced around the world. In countries like Brazil, South Korea, and South Africa, there is a pattern of dramatic increases in credit card use and entrenched neoliberalization alongside exponential evangelical growth. These card-carrying Christians are changing religious and political landscapes, as well as economic realities throughout the world. Faith in the market has become faith in the self.

Colombia’s ongoing armed conflict sustained by drug economies alongside licit political economies of war, provides a salient atmosphere in which to consider the ways that the financial system can operate, and support, systems of death. Meanwhile, millions of Colombians continue to march and resist, in the hope that these systems of death—fostered by neoliberalization and anti-democratic fundamentalism, backed by a faith in the “free” market and rule of the elite minority—may be overthrown by the forces of peaceful resistance, unbridled creativity, and an unflinching questioning of the status quo.

Rebecca C. Bartel, Ph.D., is Associate Professor in the Department for the Study of Religion, Associate Director of the Center for Latin American Studies, and the Fred J. Hansen Chair of Peace Studies at San Diego State University.