If you were to search for the word “feminicidio” (feminicide), it is highly probable that you would encounter Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, amongst your findings. It is undeniable that the prevalent cases of feminicides in the ‘90s in this city, which caused the evolution of the term from femicide to feminicide to represent the systematic dimension of this issue, cemented the inextricable relationship between this word and the northern Mexican city in the social collective imaginary. But today this issue is not bound to that specific geographical area, and its pervasiveness has created roots across Latin America and the world. And although feminicidio is not widely used to understand the gendered and deadly violence that women experience at the hands of men everywhere, non-Latin American countries are not exempt from this sociocultural phenomenon.

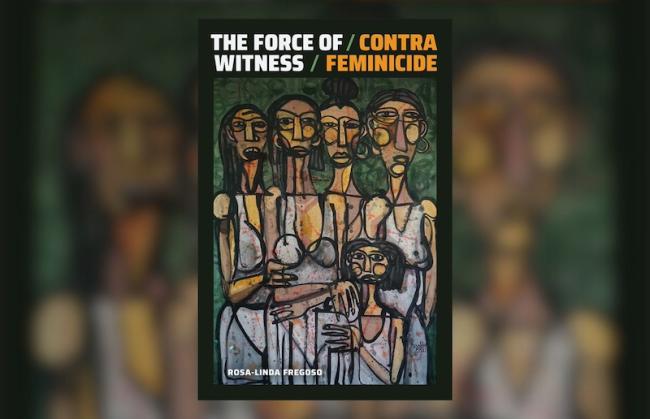

Through the invitation to her readers to become witnesses, Rosa-Linda Fregoso’s The Force of Witness: Contra Feminicide becomes a critical roadmap that invites its readers to develop radical hope and collectivity in the form of what Mexican Indigenous and original communities define as tequio – “a ‘practice of reciprocity’ or ‘reciprocal help.’” This act of witnessing, despite bringing our attention again to Ciudad Juárez, calls for planetary responses that go beyond the examples laid out over the six chapters, three interludes, the prelude, and the postlude that comprise this book. In other words, Fregoso invites us to develop a radical form of solidarity by witnessing and becoming present.

The Force of Witness encompasses not only a clear explanation of the framework that helps her expand on the concept of feminicide, but also a critical overview of patriarchal and colonial systems that silence women, feminine, and feminized bodies while upholding the structures that profit from this violence. Her position against the pathologization of gender violence echoes the growing critiques of the Mexican media apparatus, which continues to treat this issue as a mental health problem, locating responsibility outside of the realm of the social and justifying these acts as involuntary. In opposition to that, Fregoso’s position is that “if we treat gender violence as rooted in an assemblage of racist and heteropatriarchal structures, then there is a greater opportunity to design and develop more appropriate long-term strategies and transformative social policies.” Thus, Fregoso points towards a more intersectional approach that addresses gender violence from a nuanced perspective and not a monolithic issue.

While this book does not skimp in its usage of academic theory, the dialogue between Fregoso and other scholars in border studies, gender studies, and Mexican and Latin American studies fortifies the critical study of the artists she presents throughout the book and who actively work on visibilizing and amplifying the voices of those who have been subjected to state-sponsored violence. Focusing the works of Lourdes Portillo, Diane Kahlo, Irene Simmons, Verónica Leiton, and the installation of the Ni Una Más (Not One More) crucifix, Fregoso points towards spaces of collectivity where witnessing and bearing together becomes an essential practice to the creation of community. The book also reflects on the ruling against the Mexican government for “failing to guarantee the life, dignity, work, and liberty of women” by the Permanent People’s Tribunal and the struggles of migrant communities who in their path towards a less precarious future are confronted with a bilateral state complicity that deepens their wounds.

Fregoso’s writing proves to be a crafty exercise that can interweave activist-mothers, the memories of victims of feminicide, and expert witnesses, with her own experiences as a woman who had to flee her home in search of a safe environment for herself and her daughter. Having grown up in a similar setting as the one she describes in her book, I can certainly say that this issue has been willingly ignored by both the public and private spheres of the Mexican culture—although it is clear that this does not include feminist activists that have continuously brought this issue to the core of sociopolitical and cultural conversations as an urgent matter to be resolved.

In 2023, more than 3,000 women were victims of feminicides. In other words, approximately 10 women are victims of feminicide daily in Mexico. The efforts in finding the bodies, much as in the case of Marisela Escobedo’s journey towards finding the remains of her daughter Rubí presented by Fregoso in the first chapter of her book, have been a task mainly undertaken by the mothers and, at times, by other family members. The case of Marisela Escobedo might be one of the most emblematic, partially thanks to the media coverage and a recent documentary produced and distributed by Netflix called The Three Deaths of Marisela Escobedo. Escobedo became a symbol of this struggle after she brought to justice her daughter’s murderer, only for him to be acquitted by the judges in the case after he confessed to his crime. She nevertheless persisted and gained national and international attention in her seek for justice. Marisela Escobedo was killed just steps away from the governor’s palace after two years of a continuous and restless fight not only against Rubí’s murderer, but with the State and its forces.

The state was nowhere to be found in Marisela’s case and continues to be missing in action for numerous cases regardless of the public attention they receive. That is why Fregoso’s book is not only enlightening but hard to read at times because of what it places at the center of the conversation. Through the force of witness, which “involves a collectivity forged on the basis of ethical and engaged planetary obligations and interdependency,” Fregoso returns us readers to a pressing issue that we might consider outside of our field of action. But the accumulation of state violence exacerbated by the War on Drugs of former President Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) that led to the threatening presence of the military elements on the streets, was a sign that for many of us meant that no one was safe and there was virtually nowhere to run and no one to help. This period, marked by a state of exception that transferred all power to the state in its “war,” was then later followed by a term of continuity with Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018). And although López Obrador ran a campaign that promised to return the militaries to their quarters, the strategy remained the same. Now, after a historic election that culminated with Claudia Sheinbaum being elected the first-ever woman president of Mexico, there are dim hopes for this to change. As we experienced during her time as the Head of Government of Mexico City, the display of armed forces aimed to suppress women protesting sexual violence and gender inequality was still the reglementary position of the government led by her at a state level and by López Obrador at a federal level.

Although some might feel that the book’s fragmentary aesthetic could make its reading repetitive, I would argue that this element highlights the point of contact that gendered violence has across cases. By reading the instances outlined in the book, we, as newly added witnesses, become part of a much larger community with certain responsibilities around this issue. Although the book has only so many examples, the message is clear: we cannot stay put while we see violence unfolding right in front of us every day. To a certain extent, it becomes imperative that we, individually and collectively in our communities and through the state, keep the conversation open around femicides: the causes, the consequences, and the deep-rooted everyday dynamics we culturally, socially, and politically brush aside as minimal and that we must return to the center of our attention. By doing this, we can focus on actions we can employ to denaturalize and diminish feminicide rates and gendered violence more broadly.

Hence, by experiencing repetition, we become witnesses and therefore carries of tied responsibilities. A book like The Force of Witness: Contra Feminicide cannot be read as a totality. It is important that this book is recognized as a work in progress that should not be conceived as completed until the issue is eradicated. The work of Fregoso can and should be updated, expanded, and discussed. If her planetary aim posed in the prelude of the book is taken seriously, then the next step is to find, trace, and explore the points of contact this book affords. This issue has found its way beyond Mexican territory—that is why it requires collective attention. We are required to witness; we are required to respond.

Francisco G. Tijerina Martinez is a Ph.D. Candidate in Hispanic Studies at Washington University in St. Louis currently working on a dissertation titled Mineral Bodies: Violence, Extraction, and Possible Futures in Contemporary Mexican Literature Written by Women.