This interview was translated by Nancy Piñeiro and has been edited for clarity and length.

This is the fifth installment in a collection of interviews with Indigenous and feminist media makers and community organizers in Bolivia. They explore building community media, Indigenous liberation, and feminist social change through grassroots journalism and people's movements. Read the other interviews here.

Community radio has been one of the backbones of union and social movement organizing in Bolivia for decades. Radio still plays a crucial communication role, particularly in rural areas that lack electricity and the internet. Such a medium was pivotal during key uprisings among campesino, miner, and Indigenous movements throughout Bolivian history.

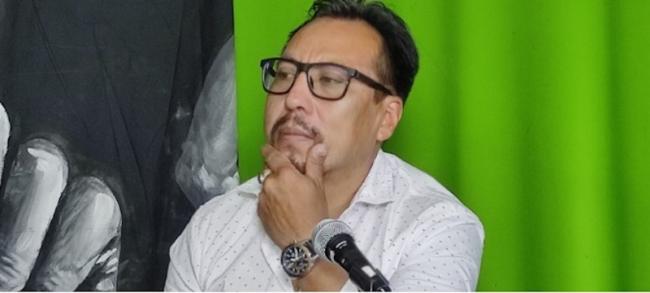

Journalist José Aramayo Cruz has had a fundamental role in such media support for movements through his work for Radio Comunidad, Prensa Rural, and other journalistic initiatives linked to Bolivia’s largest campesino movement, the Unified Syndical Confederation of Rural Workers of Bolivia (CSUTCB).

The power of such work was on display when Aramayo himself faced violent repression during the 2019 coup against former President Evo Morales. The corporate media played a crucial part in this coup, building a narrative that contributed to the right-wing overthrow of Morales.

“A big factor here was hegemonic media, big media,” Aramayo explains about the media’s role in the 2019 coup. “Because they were able to disseminate and build a uniform discourse in most media, not all of them, but most of them, so that the population could change their thinking. They also ‘heated up’ the streets in a sort of soft coup scheme where big media were of vital importance, especially among the Bolivian population where they planted doubts, antagonism, and antipathy against the Indigenous movement and against its biggest leader back then, Evo Morales.”

In this interview, Aramayo reflects on this tumultuous period in Bolivia, discusses the role of community radio in supporting campesino and Indigenous movements in the country, and analyzes how radio still holds a central space in rural and urban Bolivia’s everyday life and political struggles.

Benjamin Dangl: I’d like to ask you a few questions about your journalistic work, especially in radio. Can you start by telling me why and how you began working as a journalist?

José Aramayo Cruz: My name is José Aramayo Cruz. In fact, I studied art at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés. I’ve done artistic work bit by bit since 1995, approximately, until 2011. I created the Otro Arte Foundation, which supported and benefited emerging young artists. There was also Otro Arte magazine, where we disseminated Bolivian art. That was the first phase in my life. I also did sculpture work until 2013, more or less.

From then on, I built an alliance with the CSUTCB [Unified Syndical Confederation of Rural Workers of Bolivia] to support them with communication. A few years before that, I was doing communications for culture, and then I started doing communications for development, with the aim of positioning and giving social organizations a communicational platform. Back then they had a very important protagonist role as they were supporting the Pacto de Unidad, a process undertaken by Evo Morales Ayma as president. He was, and still is, the first affiliated member of the CSUTCB, a campesino movement.

At that time, I started working at Prensa Rural for the Indigenous movement. That newspaper saw the light for the first time in 2014; it was launched at the intercultural offices on February 3rd, and the next year, we moved to the CSUTCB to work on the newspaper to this day. In 2018, I became in charge of Radio Comunidad, a media outlet that belongs to CSUTCB, a very important radio.

Thanks to this, we were able to build a communication editorial line for the [union] organizations, which, in my opinion, make up the most important organization in the country: the CSUTCB, which brings together more than 4 million affiliates. Together with Radio Comunidad and Prensa Rural, we were able to build a communications proposal.

Sebastián Moro was head of communications, an Argentine journalist who then tragically died when he was physically assaulted between November 10th and 16th [2019] when Jeanine Añez took power by force.

We’ve all suffered persecution; those were very difficult moments. Personally, I was tied to a tree to set an example for the journalists who were supporting the Indigenous movements. They mistreated Bolivian and international journalists who were in favor of the then President Evo Morales in very hateful and racist ways.

Now, we’re building a new project, Comunidad Tevé, to reach the Bolivian population, this time not only for social movements but for the Bolivian population, with a television format that can be streamed and transmitted through IP signals. The 21st century allows for that and demands communication of different characteristics.

BD: Regarding the practices of such journalism, could you explain your methodology in covering, for example, a congress of the CSUTCB or preparing an interview with one of its members, or other social organizations? The work you do is different from the one done by commercial media. Could you talk about this practice from your perspective or through an example?

JA: Well, as alternative or mid-size media, we can’t compete with big media due to a lack of resources and because the state is not supporting small and medium-sized endeavors right now. So, we need to be creative in our methods. We must use technology to move from one place to another without many resources.

For example, some compañeros only work covering a certain number of congressmen or politicians who can provide funds to support them. Basically, in our case, we have an opinion and analysis program called Encuentros where we invite Indigenous/originario movements and leaders, those who are protagonists in Bolivian society, and we ask them questions, provide analysis, and respond to the population.

We’ve seen that the demand for the internet and immediacy through social media are very important. It allows us to disseminate news faster and more efficiently. Conventional journalism, in radio or TV, has been somewhat displaced by social media, and even before someone hears something on the radio, they have it on their phone.

BD: Could you share your perspective on the role of community radio in rural and urban areas in Bolivia, and why it’s still so important in this context?

JA: Well, this is because the radio has been a very strong school for us in our country. It has been used not only for informational purposes but also communicative purposes, in the sense that for many years people have communicated with each other through the radio, leaving messages, selling or offering things.

Radio has been a means of communication in rural areas that has even strengthened social relationships, as people send each other greetings and congratulatory messages for baptisms or birthdays. On the other hand, the necessary information in a community or municipality was broadcast through the radio as the easiest way to reach everybody. That communicative aspect of radio in the 1970s and 80s, even a bit before and until the 90s, is still alive in the rural area.

The last time I was in rural areas, I saw the importance of radio in some places; the population is really interested in their radios; they value them, take care of them, and give them concrete importance. The internet is not as available in some places as it is in the capital cities, even considering that compared to other countries our internet in the cities is slow. So not only in the rural area, but it’s also really slow and satellite internet is very expensive. So, the only effective communication mechanism is the radio.

In La Paz or Santa Cruz or Cochabamba, the radio is maintained because it’s still part of the work environment. People who are working don’t have time to be watching TV, unless they’re maybe in a restaurant. But drivers and industry workers have the radio as their closest companion. In addition to providing information, it also offers entertainment and advice that can distract them from their everyday work and make their afternoon or morning more pleasant while they receive information. In that sense, I think the radio is a very important element in our city.

Radio Kawsachun Coca, which reaches different areas of our country, has created a very valuable circuit of connection with the rural area. The communities consider it their own because they identify with the problems discussed there, the content, and its political goal of changing the country through changing the rural and peasant movements.

That class struggle between the Indigenous peasant movement and the urban movement, the civic society platforms, and everything in La Paz polarizes the dynamics of communication since people identify themselves with what they listen to, right? Some identify with Radio Panamericana, others with Kawsachun Coca, and some say this is the real voice, this is a truthful media. Others think it’s partial and polarized. It allows you to understand that difference a bit and aspire to a communicational democratic freedom.

It’s really important to support the community, Indigenous, campesino, alternative media, and small media who are in this struggle to inform the Bolivian people with the truth, veracity, transparency, and clarity. We are right now leading a struggle to survive and work for the people.

Benjamin Dangl is a Lecturer of Public Communication and Journalism at the University of Vermont. He has worked as a journalist across Latin America for over two decades covering social movements and politics. Dangl’s most recent books are The Five Hundred Year Rebellion: Indigenous Movements and the Decolonization of History in Bolivia and A World Where Many Worlds Fit.