Traveling through the Cuban countryside shortly after the 1959 revolution, one American political activist applauded the expanding access to many goods, including food.

“Many of us in the United States may call the Cuban Revolution ‘communist,’” he wrote, “but what impressed me was its great emphasis on consumer goods.” Indeed, Cuban revolutionary leaders initially held out a tantalizing vision of equality and abundance, with interlaced promises of food sovereignty, social justice, and universally high standards of living.

But by 1961, food shortages had begun to afflict Cuban cities. The shortages reflected a combination of factors: the disruption of old distribution networks, U.S. economic aggression, and the rising purchasing power of the Cuban countryside, which meant meat and produce were consumed locally, not sent to urban markets. Those changes had huge political ripple effects. In long lines outside food stores women seethed angrily. The black market surged, prompting government crackdowns. New signs outside Havana butcher shops announced, “We don’t have meat, but we have dignity and sovereignty.” Finally, in March 1962, speaking live on television, Fidel Castro held up a ration book. The revolutionary dream of abundance was over.

The Cuban experience captures dilemmas perhaps inherent to any revolutionary transformation. How to increase food production in the face of landowner hostility? How to retain the loyalty of the urban middle class despite downward pressures on consumption? How to fully dismantle the legacies of monoculture, extraction, and unequal global trade relations that have so long scarred the economies of the Global South?

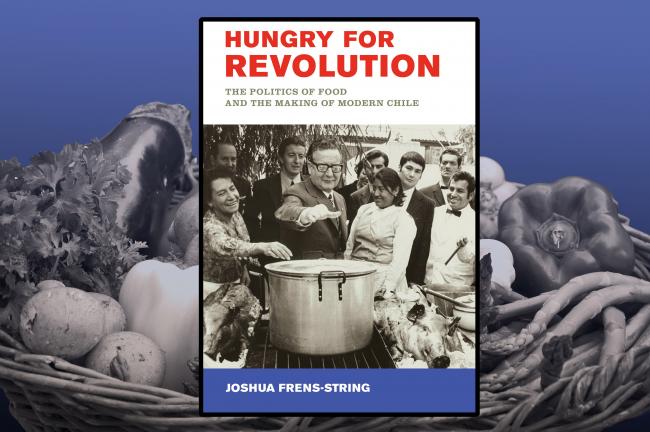

Joshua Frens-String’s new book, Hungry for Revolution: The Politics of Food and the Making of Modern Chile, offers exceptional insight into these questions. Frens-String tells the story of Chile’s 20th-century political conflicts through the prism of food politics. Beginning in the early decades of the century and culminating with Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity (UP) government from 1970 to 1973, Frens-String argues convincingly that food—as both symbol and sustenance—was central to demands for democratic inclusion, social justice, state intervention, and national sovereignty. The left’s evolving vision of socialism, he writes, “grew out of the simple belief that urban workers and their families were entitled to nutritional equality.”

Chapters 1 and 2 establish the longstanding centrality of food to leftist politics in Chile. Frens-String shows how urban consumers, labor activists, and leftist political groups mobilized around hunger, the most basic and tangible expression of exploitation and inequality. As Frens-Strings documents, grassroots activists made food a central political issue. For example, the broad consumer coalition Workers’ Assembly for National Nutrition launched Hunger Marches after World War I. And the Communist Party and the progressive women’s group Movement for the Emancipation of the Chilean Woman protested food monopolies, speculation, high prices, and scarcity starting in the 1930s.

These popular protests forced politicians, social reformers, and nutrition experts to take the question of food equity seriously in the 1930s and ‘40s. Various government agencies took decisive action, especially during the Popular Front period. Chile’s new National Nutrition Council researched and publicized the inadequacies of working-class diets. The Comisariato, one of Latin America’s first consumer protection agencies, capped food prices and shuttered non-compliant retailers. State-run popular restaurants and milk bars made protein-rich foods accessible to working-class families. Most importantly, this period consolidated a new common sense about the state’s necessary role in guaranteeing social rights. That conviction faded somewhat during the early Cold War, as competing discourses around nutrition emphasized solutions like more efficient farming or closer management of working-class consumption practices, but it revived in the 1960s.

By that time, a growing consensus held that to truly achieve food security and food sovereignty, Chile would need deep agrarian reform. The Christian Democratic administration led by Eduardo Frei (1964-1970) accordingly launched one of the most substantive land reform programs in Latin American history. Frens-String argues that Frei’s agrarian reform was never simply about creating a more stable and prosperous class of small farmers; it also aimed to improve the provision of urban consumers. The Frei administration could boast of some successes: throughout the 1960s rural incomes and consumption did rise and national production of a few crops like barley and corn soared. But the period also raised expectations that were ultimately not fulfilled. In particular, the Frei administration’s redistribution of land fell far short of its promises, awarding plots to just 20,000 of roughly 250,000 landless peasants. This disappointment was augmented by the return of inflation and scarcity by the late 1960s. When the socialist candidate Salvador Allende narrowly won the 1970 presidential elections, many Chileans found themselves ready for more radical solutions.

In chapters 5 and 6, Frens-String uses the thematic focus on food to recover the early promise and relative abundance of the UP years, memories now virtually drowned out by ensuing depictions of the period as one of shortages, hardship, and instability. Rather than narrate the 1970-73 period as a prelude to disaster, Frens-String String recreates the excitement of the revolution’s first year, which was a bonanza for Chile’s popular classes. The combination of wage hikes, lower unemployment, and price controls vastly increased working-class purchasing power. Domestic production of flour, milk, and cooking oil soared. Efforts to streamline inefficient forms of food distribution eliminated bottlenecks between farm and table. A Chilean-Soviet fishing pact increased production of local seafood. The UP’s accelerated agrarian reform resulted in banner harvests in 1971 and 1972. The early UP administration should be seen as “an unparalleled period of plenty rather than a moment of struggle and sacrifice,” Frens-String argues, adding “this consumer rhapsody…became a defining, though often forgotten, feature of Salvador Allende’s first year in power.”

Fresn-String also explores popular mobilization around food to show how sustenance was linked to empowerment. Chapter 6 examines pro-UP consumer activism, especially the supply and price control boards known as JAPs (juntas de abastecimiento y precios). JAPs gave ordinary citizens a role in distributing foodstuffs, monitoring sales at local stores, and serving as honorary consumer-inspectors who ensured fair economic transactions in their communities. JAPs also became forums for debating concepts like fair prices and reasonable profit, rethinking the very foundations of everyday economic life. Not surprisingly, JAPs soon became a key target for the growing anti-Allende movement, which accused them of politicizing food access and replicating the policing role of Cuba’s controversial Committees to Defend the Revolution.

Frens-Strings provides excellent analysis of how food became a rallying cry that helped cement alliances within the anti-Allende movement as conflict escalated in 1971 and ‘72. The famous December 1971 March of the Empty Pots and Pans, led by conservative women, was a turning point, he notes. It was the first mass public demonstration against Allende. It helped enflame and radicalize the anti-Allende opposition and led to the creation of new anti-UP groups like Poder Femenino and the National Front for Private Enterprise. Key to these new coalitions was the historic displacement of women consumers’ fury over scarcity and high prices from shop owners to the government. This shift enabled the emergence of a powerful new alliance of women consumers, merchants, and large landowners that paved the way for the coup that toppled Allende.

What’s more, this unlikely alliance of female consumers, urban retailers, and rural landowners helped pry open the commonsense notion first forged in the 1930s that fair and equitable distribution required some level of state intervention. Instead, the anti-Allende opposition now argued that excessive state interference in the production and distribution of food had produced only crisis. These claims paved the way for the post-coup dismantling of the welfare state. While the origins of Chile’s famous neoliberal experiment during Pinochet are often traced to a U.S.-trained group of economists known as the Chicago Boys, Frens-String shows how the defeat of more social understandings of democracy and their replacement with a commodified version of individual “choice” emerged out of the street-level conflicts of the UP years.

After the coup, the Pinochet regime unwound the UP reforms. It reprivatized food production and distribution, disbanded the JAPs, ended price controls, and returned expropriated land. Hunger rose accordingly. But Frens-String ends on a more positive note by quoting a sign from Chile’s huge 2019 protests: neoliberalism had been born in Chile, the sign read, but would also die there. The militant demand for a fair and inclusive economic order has resurged, and this remarkable book helps us understand the century-long struggle behind it.

Michelle Chase, who teaches at Pace University, is the author of Revolution within the Revolution: Women and Gender Politics in Cuba, 1952–1962. She is a member of NACLA’s editorial board.