This is an excerpt of an investigation by Avispa Midia and CONNECTAS, originally published in Spanish.

La Encrucijada Biosphere Reserve (REBIEN, Reserva de la Biosfera La Encrucijada), one of Mexico’s greatest environmental treasures, is home to an important system of wetlands, including mangroves up to 115 feet tall. These are threatened, though, by an enormous extension of monocrop oil palm plantations.

The REBIEN lies in the coastal region of Chiapas, in Mexico’s southeast. It was created by presidential decree on June 6, 1995 and is regulated by a Management Plan that was published in 2000. This states that in mangrove areas, activities “that alter the ecological equilibrium” are prohibited, except in cases of “preservation of scientific research, monitoring, education, and training, under strict regulation and supervision.”

However, over the last few decades, the ecological equilibrium in La Encrucijada has been altered. “There are more than 7,000 ha [17,300 acres] of palm planted inside the REBIEN,” said Juan Carlos Castro Hernández, current director of the REBIEN, who forms part of National Commission of Protected Areas (CONANP).

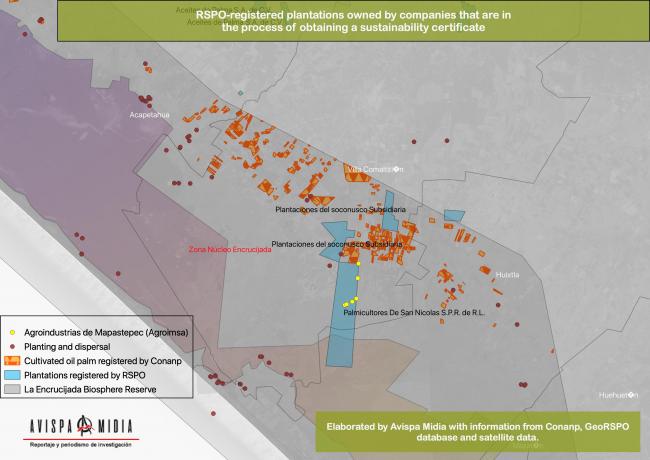

Avispa Midia requested a report and georeferencing information from the CONANP regarding oil palm plantations within La Encrucijada. The agency sent back two data sets that report the presence of producers and palm dispersed throughout the reserve.

One of the documents, titled Appendix: Southern Border, Isthmus, and Southern Pacific Region of the CONANP, with no date of publication, reports that there are at least 518 palm producers within the REBIEN.

The document’s figures are conservative, since they don’t contain a complete list of palm plantations within the reserve—satellite images can identify palm groves that aren’t included in the database.

Matilde Rincón, Mexico landscape manager at Earthworm Foundation, confirmed that they have identified 500 producers who cultivate a total of 19,030 acres (7,700 ha) of palm within La Encrucijada. Earthworm Foundation works with businesses and small producers in Chiapas to promote the sustainability of this crop. “Sixty percent of them struggle to meet government land-use standards,” Rincón said in an article by Earthworm.

The proliferation of large palm plantations has been on the CONANP’s radar since 2014. According to the agency, these groves have grown by more than 81,540 acres (33,000 ha) in the REBIEN’s area of influence—the area surrounding the reserve, which is not regulated, but is supposed to benefit from conservation efforts and is strongly ecologically linked with the park. Now the exotic plant had invaded mangrove ecosystems in the core zones.

Oil palm is so invasive that even the plantations outside of the reserve should be regulated, “because there’s even palm on the banks of the canals and the seeds can migrate, whether that be by water currents, or hypothetically, from animals,” said Castro, the director of the REBIEN.

Green Certification

On a tour of the Reserve, Avispa Midia found that in the middle of hundreds of palm plantings, on the banks of the San Nicolás river, lies a processing plant of the company Industrias Oleopalma. It’s the first plant the company built within the REBIEN’s area of influence, in 2000.

According to the Mexican Palmgrowers Federation (Femexpalma), processing plants must be installed as close to the plantations as possible, since the oil must be extracted within three days. There are 18 palm processing mills in Mexico, 12 of them in Chiapas. Seven of these are in La Encrucijada’s area of influence, including Oleopalma’s plant.

This company is relevant to the product’s current market because in March 2020 it became the first Mexican company to be certified sustainable by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), which states that its goal is to reduce the negative impacts of oil palm cultivation on the environment and communities.

RSPO certification began in Switzerland in 2004 under the leadership of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) along with financiers like the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group, and multinational companies that buy palm oil, such as Cargill, Nestlé, Unilever, PepsiCo, Procter & Gamble, and others.

However, the RSPO has been criticized around the world for failing to deliver on its promises. The Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) published a report called "Burning Questions: Credibility of sustainable palm oil still illusive,” which revealed generalized fraudulent assessments by the RSPO. It also documented that abusive labor practices, forest clearing, territorial conflicts, and even human trafficking had been permitted on plantations belonging to RSPO members. In 2019, the EIA stated that the RSPO still hadn’t taken significant measures to address these problems.

Greenpeace International’s report Destruction: Certified, published in 2020, focuses in on how 30 years after product certification was implemented in supply chains, it is functioning as greenwashing for businesses.

Earthworm Foundation’s Rincón says that, at a global level, the RSPO doesn’t allow the purchase of oil that comes from protected natural areas; however, she affirms that Mexico is the exception because the cultivation and sale of palm from La Encrucijada is permitted.

The Government’s Solution: Shrink the REBIEN

The CONANP and the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) attribute the problem of the spread of palm to poor control by producers, so they have looked for strategies to legalize it. In October 2015, they presented the Preliminary Supportive Study for the Modification of the Declaration of 1995 of the REBIEN, which sought to remove areas where there are crops, livestock, and fisheries from the reserve.

Both agencies wanted to reduce the size of the reserve in order to regulate oil palm, arguing that “the goal is to adapt zoning, in particular incorporating areas with well-conserved ecosystems into the core zones, and removing areas where agricultural, ranching, and fishing activities are conducted,” as the document Avispa Midia had access to states.

They sought to remove an area of 8,345 acres (3,377 ha), of which 1,841 (745 ha) belong to El Palmarcito Core Zone and 6,504 acres (2,632 ha) to La Encrucijada Core Zone. This proposal never moved forward.

In 2016, the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) issued General Recommendation 26/2016, for addressing impacts on protected natural areas and human rights. It highlighted the degradation of the REBIEN, explaining that for several years, the reserve has faced “the use of these lands for the establishment of oil palm plantations.”

That same year, instead of going after the plantations, CONANP hired the nonprofit organization Naturaleza y Redes A.C. to run a project called Strengthening African palm control strategy in the REBIEN, which only focused on the problem of seed spread. Information gathered through this project helped to eradicate and control individual oil palm trees covering 28.4 acres (11.5 ha) inside the reserve.

Poulette Hernández, co-founder of the Digna Ochoa Human Rights Center, clarified that this is no easy task. She explained that people are mistaken in thinking that palm is like any other tree that can be disposed of by being cut down and burned. REBIEN’s Castro agrees that eradicating this crop is not simple. He explained that palm trees can’t be cut down with a machete, and even doing it with a chainsaw is very complicated. What’s more, all of the brush must be removed from the site, since it can contaminate the mangroves.

Those Responsible for the Expansion

The CNDH’s General Recommendation 26/2016 states that the advance of this crop in the REBIEN is not an accident: “it has to do with a change in production promoted by the state government for several regions of Chiapas, which has led to its expansion to lands in this conservation area [La Encrucijada].”

Castro was quick to emphasize that the expansion of oil palm began long before his tenure as director of the REBIEN. He stated that it hasn’t been penalized due to the size of the reserve “and maybe because of political pressure,” although, he reiterated, he doesn’t know about the early phases, since he didn’t witness the process.

What is known is that between 2007 and 2012, the state government promoted the crop through the Productive Conversion Program and distributed four million plants for free without overseeing where they would be planted. It received 165 million dollars for this from the International Finance Corporation. In 2011, this entity granted another loan to continue expansion of the agricultural zone for two more years.

The federal government also drove palm expansion through Agricultural Trust Funds (FIRA). By way of the Production Stimulus Incentive program, linked with Femexpalma, it proposed equipping producers with infrastructure and technology to increase productive capacity for oil palm.

This financing was earmarked primarily for small producers. However, wealthy businesspeople who have palm inside of La Encrucijada also benefited.

Support from Sembrando Vida

Palm cultivation on the Chiapas coast has gotten new momentum with the government program Sembrando Vida (Sowing Life). The directory committee of La Encrucijada said that there are oil palm producers who have “slipped through” and are growing palm within the protected natural area, even though “they know they have to stop.”

Rincón said that there are producers who are combining their palm groves with cacao as part of this government program, which purports to address rural poverty along with the country’s environmental decline. “The people in Sembrando Vida pushed an agricultural model in which cacao is grown within the palm groves, so there is a diversified crop,” said Rincón, who added that producers share a commitment to eliminate palm “at some point” if it’s in a zone where it’s prohibited within the reserve.

Palm expansion in Mexico also has the support of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (SADER).

Breaking an International Agreement

The story of the REBIEN is not unique in Mexico. Oil palm cultivation in Mexico, a study authored by Dr. Anne Cristina de la Vega-Leinert (member of Mexico vía Berlin and the University of Greifswald) and Daniel Sandoval, among others, and edited by the Center of Studies for Change in the Mexican Countryside (CECCAM), confirms that after years of palm production in the country, protected areas in Chiapas have been impacted: principally, La Encrucijada Biosphere Reserve and Palenque National Park.

The biggest problem, said Claudia Ramos Guillén, is that these policies are not going to stop, because millions of dollars are in play. “Palm comes from an expansionist policy at the international level, primarily affecting ecosystems like that of La Encrucijada,” she said. “So, the governments end up adjusting to the demands of the international market.”

This work was completed by Santiago Navarro F. and Aldo Santiago for Avispa Midia and Connectas, in partnership with Aristegui Noticias and Pie de Página, within Connectas’s ARCO initiative and with support from the International Center for Journalists in the framework of the initiative for Investigative Journalism in the Americas.

Santiago Navarro F. is an economist, journalist, photographer, and documentary filmmaker. He is co-founder of the investigative journalism portal Avispa Midia.

Aldo Santiago is a documentary filmmaker and independent journalist. He is also an editor and correspondent for Avispa Midia.