Hugo Chávez died eleven years ago. The period since has been one of the most difficult in Venezuela’s history. From 2014 to 2021, Venezuela suffered one of the worst economic crises in modern history. The economy contracted by 86 percent. Poverty rose to an estimated 96 percent in 2019. Inflation reached an absurd level of 350,000 percent that same year. In 2018 nearly a third of the population suffered undernourishment. And roughly a quarter of Venezuelans have fled in an unprecedented out-migration that now exceeds 7.7 million.

The economic situation has improved in the last two years. The Council on Foreign Relations reports economic growth of 8 percent in 2022, 4 percent in 2023, and estimates that it will be 4.5 percent this year, in part due to the recent (but fragile) easing of US sanctions against Venezuela. Inflation has also been tamed, dropping to a comparatively modest if still quite high 360 percent in 2023.

Venezuela’s political situation has also been extremely challenging. Chávez’s handpicked successor, Nicolás Maduro has faced waves of opposition intransigence and violence. Maduro has responded with repression, directed not only against elites but often also the popular sectors that formed Chávez’s core support base.

To what degree should Chávez be held responsible for the crisis that has engulfed Venezuela since his death? How should we assess Chávez’s legacy in light of the crisis?

Two theses have emerged in response to these questions. The first blames Chávez for much, and in some cases nearly all, that has transpired since his death. The argument here is that Chávez was an incompetent authoritarian who destroyed Venezuela’s economy and eroded its once-vaunted democracy. Further, Chávez chose Maduro, who finished the destruction Chávez started. The second thesis holds that Chávez bears little to no responsibility for the country’s descent. The crisis is instead laid at the feet of US imperialism; some who subscribe to this thesis also blame Maduro’s misguided and autocratic policies.

Neither argument fully captures the reality of the Chávez and post-Chávez eras, although the second is a bit closer to the mark. There is no doubt that the US bears immense responsibility for the profound suffering Venezuelans have experienced in the last decade. This is true, most directly, because of the impact of US sanctions, which particularly since 2017 have decimated Venezuela’s economy and its oil production. The US has also supported the most far-right elements within the Venezuelan opposition, most infamously during the 2019-2023 “interim presidency” of Juan Guaidó who, among other things, attempted to foment a military coup and backed a tragicomic sea invasion by US mercenaries.

It is also true that Maduro’s policies have been disastrous and autocratic and have directly contributed to Venezuela’s socioeconomic and political malaise. This does not mean that Chávez is fully off the hook—rather, it points to the need for careful assessment of the Chávez years, with attention to his successes and failures.

Chávez’s Achievements Were Real and Impressive

Chávez’s many and significant achievements demand highlighting, since he is subject to unfair critiques and caricatures in mainstream accounts. After a rocky start (due to low oil prices and conflict with the opposition), Chávez presided over years of robust and sustained economic growth in Venezuela, averaging 4.5 percent a year from 2005-2013. Chávez reasserted state control over the state oil company, PDVSA, and directed enhanced oil revenues to the poor, with Venezuela’s social spending doubling between 1998 and 2011. The government used price controls, direct state provisioning through newly created missions, and subsidies to partially decommodify health care, education, social services, housing, utilities, basic goods, and other economic sectors.

This helped bring about major social gains. Poverty was nearly halved between 2003 and 2011, with extreme poverty cut by 71 percent. School enrollments rose and university enrollments more than doubled, with unemployment cut in half. Child malnutrition was cut by nearly 40 percent, and Venezuela’s pension rolls quadrupled. Inequality declined steeply, with Venezuela’s Gini coefficient dropping a full tenth of a point, from 0.5 to 0.4 from the early to late 2000s. By 2012 (and through 2015), Venezuela had become Latin America’s most equal country.

On the political front, Chávez reinvigorated Venezuela’s democracy, with the 1999 Constitution committing Venezuela to “participatory and protagonistic democracy,” in which ordinary citizens rather than bureaucrats or party officials were tasked with directly making decisions about issues affecting their lives. As I show in my book, Democracy on the Ground, Venezuela’s participatory initiatives led to impressive gains in popular power at the local level, including in cities governed by the opposition.

Chávez was also committed to, and quite skilled at, representative democracy, notwithstanding criticisms he frequently received (many of which have no basis in fact). In his fourteen years in office, he and his party were tested electorally over a dozen times. Chávez won time and time again by large margins, with his widest margin being 26 points in 2006 and his narrowest 11 points in his final election in 2012. The ruling party, in its various incarnations (first as the Fifth Republic Movement and then as the United Socialist Party of Venezuela), was almost as successful, winning twelve of fourteen major elections during Chávez’s presidency.

Chávez notably conceded defeat immediately on the occasions when his party lost an election. By transforming Venezuela’s political terrain in a way that forced the opposition to “play politics” on his terms, Chávez succeeded in establishing a form of left-populist hegemony. A notable indicator of this is how leading opposition parties implemented participatory policies like participatory budgeting and used rhetoric pushing concepts like popular power associated with Chavismo.

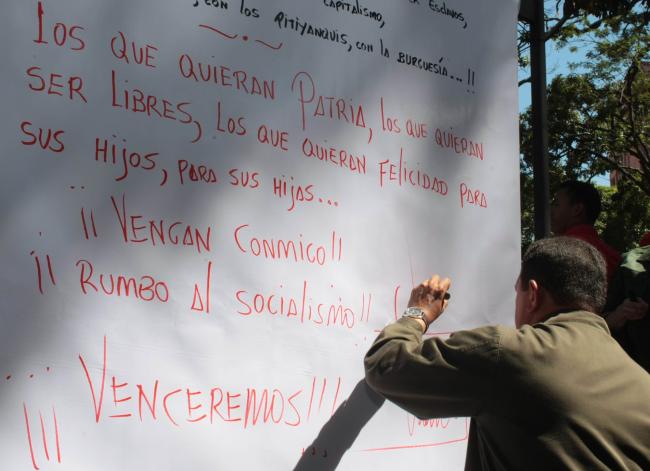

Chávez also helped popularize ideas about socialism, which he publicly committed himself to during the 2005 World Social Forum in Porto Alegre. Venezuela’s progress towards achieving socialism was, to be sure, quite mixed and uneven. Víctor Álvarez, an economist who was part of the government under Chávez, notes that private industry increased under Chávez, despite the government nationalizing a number of important industries. My research shows that ordinary Venezuelans throughout the country identified as socialists and used the language of socialism to understand and push forward their struggles for popular power and social justice. Chávez also promoted popular power organizations, such as communal councils, urban land committees, and communes that were tasked with bringing twenty-first century socialism into being.

A Legacy Marked by Crisis

Notwithstanding these achievements, Chávez’s period in office was highly contradictory. Under Chávez’s watch, corruption skyrocketed, with the state losing hundreds of billions of dollars due to mismanagement of its currency policy. Chávez deepened the influence of the military within the state, and he frequently sought to channel and control popular power. Chávez interfered with trade union autonomy and inhibited judicial autonomy, one of the most notable and ominous ways Chávez eroded representative democracy.

His government also engaged in exclusionary practices, most infamously through the use of the 2004 Lista de Tascón, which was used to punish those who signed a petition calling for a recall referendum on Chávez. Chávez centralized decision-making within the state and sought to make himself indispensable. On the economic front, Chávez utterly failed to wean Venezuela from oil dependency, with the percentage of government export revenues derived from oil increasing from 67 percent in 1998 to 96 percent in 2016.

Chávez cannot be blamed for the scale, duration, or consequences of the crisis that unfolded after his death. But several of Chávez’s policies undoubtedly contributed to the crisis. The country’s oil dependence came to a head in 2014 when oil prices declined by nearly 75% in a matter of months. Chávez’s centrality to Venezuela’s process of change also contributed to the difficulties Maduro faced in his initial time in office, most notably to the challenge of holding together the many disparate elements within Chavismo.

And Chávez deserves some share of the blame for the political polarization which has engulfed Venezuela for much of his time in office and in the years since his death. (To be sure, the US-backed opposition deserves plenty of blame for this as well.) Chávez’s willingness to flout certain democratic norms (a willingness, of course, that is found in the behavior of political leaders across the “democratic” world) arguably helped open the door to Maduro’s authoritarianism.

Ultimately, however, it is the US, the far-right opposition, and Maduro who deserve the lion’s share of blame for the crisis that Venezuela has found itself in since 2014. Chávez did not instruct opposition forces to deny the legitimacy of Maduro’s 2013 victory, nor to engage in violent sabotage in an effort to bring Maduro down in the waves of opposition-initiated violence that engulfed Venezuela in 2013, 2014, and 2017. Chávez did not instruct Maduro to respond to opposition intransigence with increasingly violent repression. Nor did Chávez instruct Maduro to suspend a 2016 recall referendum, delay 2016 gubernatorial elections, dissolve the National Assembly, repeatedly erode the rule of law, and engage in widespread human rights abuses, including against the poor and against popular-sector dissidents who in some cases have protested against Maduro in the name of Chávez.

Chávez cannot be blamed for the arrogant and violent nature of US policy, which is directly responsible for an immense share of the suffering Venezuelans have endured over the last decade, and of course a leading cause of Venezuelan migration to the US, which the Republican and Democratic Parties have responded to with a predictably abhorrent mix of xenophobia and cruelty. Nor can Chávez be blamed for Maduro’s moves towards incorporating the Essequibo region of Guyana, which has earned Venezuela condemnation from Caricom, eroding goodwill established under Chávez.

Beyond the question of Chávez’s legacy, it is important to focus on the actions of the key actors shaping Venezuela today: Maduro, the opposition, the US government, and the Venezuelan people. As has been the case for years, the most important changes needed for Venezuela to progress are a full and total end to the monstrous and barbaric US sanctions regime, government-opposition dialogue, and a re-establishment of robust representative and participatory democratic institutions and processes that allow ordinary Venezuelans to exert real control over their lives.

Whatever his faults, Chávez deserves immense credit for helping rebuild the Latin American left and doing as much as anyone to resurrect the notion that another world—a world beyond the barbarity, inequity, and senselessness of capitalism—is possible.

Gabriel Hetland is associate professor of Latin American Studies and Sociology at the University at Albany and author of Democracy on the Ground: Local Politics in Latin America’s Left Turn (Columbia University Press, 2023).