Enrique Marroquín is a Catholic priest who became a hippie. During his graduate studies in Rome in the mid-1960s, he immersed himself in hippie and counterculture movements throughout Western Europe. He has told, in interviews and in his memoir, of late nights and early mornings, copious red wine, drug use, and the explosive power of The Rolling Stones.

Upon his return to Mexico in 1967, Marroquín incorporated youth subculture into his ministry, inviting rock bands to perform during mass. He also wrote about the liberationist tendencies of the Mexican counterculture movement, known as la onda, prior to its commercialization and capitalist cooptation. In large part, Marroquín argued, it was the centrality of love in the counterculture that made it a vibrant protest movement. That element resonated with his liberationist Catholicism and his visions of capacious love that could transform the world.

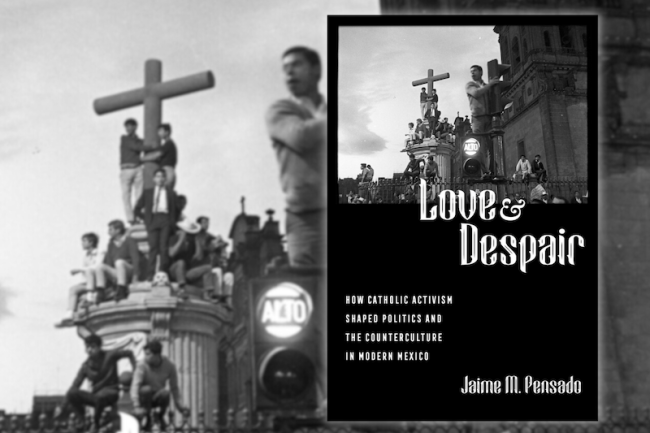

Marroquín is but one character in Jaime Pensado’s new book, Love and Despair: How Catholic Activism Shaped Politics and the Counterculture in Modern Mexico. Pensado offers an innovative cultural history of Mexico’s long 1960s (1956-1976) through a religious lens. Each of his nine chapters places Catholic individuals like Marroquín at the center of his narrative. Together, these figures amount to a collective biography of Catholicism’s multiple responses—rejection, acceptance, tolerance, participation—to a world and a country undergoing profound cultural, political, and social change.

While some of Pensado’s subjects, namely ultra-right-wing Sinarquista leader Salvador Abascal, are already well enshrined in other historical works on the era, the overwhelming majority of the individuals gracing his pages have resided in historical obscurity and footnotes. Others, like Marroquín, pop up in the historical record for their later work. Marroquín went on to become an anthropologist and taught at the Regional Seminary of the Southeast, a collaborative seminary that my own work explores for its centrality in constructing a praxis of Indigenous Liberation Theology in Mexico in the 1970s and 80s.

Pensado’s pairing of hippie priests and ultra-right activists may come as a bit of a surprise. These individuals share little beyond their faith. Their visions of a world-that-ought-to-be are starkly different. Yet, it is precisely their shared identity as Catholics that brings them together, informing and shaping their networks, their interactions with their institution and hierarchy, their engagement with papal encyclicals and Catholic theology, and, particularly, their profound emotions of love and despair that coursed through the long Sixties.

Love and despair are the central throughlines that bind the book together. Focused neither on romantic love nor incapacitating, depressive despondency, Pensado shows how Catholic notions of collective and utopian love clashed with despair and frustration to motivate activists, writers, cultural critics, and Catholic organizers to build a better world. Pensado is not the first to reckon with emotion and conviction as driving factors. Derek Penslar’s recent book, Zionism: An Emotional State, similarly critically explores the emotional foundation of Jewish nationalist movements. Humans, it turns out, are far from the cold, rational actors that classical economics makes them out to be.

Relying on emotion to understand Mexican Catholic engagement with the world, Pensado divides his book into three parts, moving roughly chronologically. The first section, “Modernity and Youth,” reckons with Catholic engagement with cinema and student politics in the late 1950s and early 1960s. His first chapter revolves around Emma Zieglar, a leader of Mexican Catholic Action, beginning in the early 1930s. By the early 1950s, Zieglar was the foreign affairs liaison of the Juventud Católica Femenina Mexicana. Her position took her around the Americas, allowing her to build networks of collaborators throughout the continent as she turned to cinema as a tool to integrate into Catholic life and education.

It is fitting that Pensado begins the book here. He shows, through Zieglar’s trajectory, how she began to think of herself as Latin American rather than just Mexican. The internationalization of culture and identity was a hallmark of the long Sixties and would shape radical activism and reformist movements alike. Second, Pensado shows how Zieglar, in her mission to bring cinema into Catholic life as an educational engagement with modernity, moderated her positions on morality and increasingly diverged from strict traditionalists like the League of Mexican Decency.

The second section, “State Violence, Progressive Catholicism, and Radicalization,” centers on journalists and progressive Catholics as they explored how Catholicism and socialism could come together and how to respond to spectacular moments of state violence in 1968 and 1971. True to his themes, Pensado highlights the progressive love that informed utopian visions of a more just world, as well as the despair over continued authoritarian state violence. While some, like Marroquín, channeled their love into academia and education in the wake of state violence, other Catholics picked up arms to wage clandestine struggle.

Finally, the third section, “The Counterculture, Liberation, and the Arts,” returns to cinema and Catholic film clubs connected to universities as spheres through which Sixties Catholics reconceptualized notions of morality, sexuality, and gender. He also, in the final chapter, explores how Mexican Catholics, from the far-right to the left, engaged with representations of the Cristero Wars, the conflict between Church and state that shook Mexico in the late 1920s. As this touchstone of Mexican Catholicism became ever more distant by the 1960s, memories and representations of it increasingly diverged—from far-right lionizations of Cristero martyrs and celebrations of righteous violence to left-wing and moderate disavowal of the strict moralism of the past.

In paradoxical fashion, the significant cultural changes that Mexican Catholics ushered in over the course of the Sixties—including more fluid notions of gender and sexuality, participation in la onda, and dialogue between Catholicism and Marxism—laid the foundation for a reactionary response that flourished across the Americas in the late-1970s and early-1980s in the form of both continued state violence and the Vatican’s silencing and marginalization of liberationist Catholics.

In multiple ways, Love and Despair is a continuation of Pensado’s excellent previous book, Rebel Mexico: Student Unrest and Authoritarian Political Culture During the Long Sixties, and an edited volume, México Beyond 1968: Revolutionaries, Radicals, and Repression During the Global Sixties and Subversive Seventies. Across these works, Pensado insists that history is the product of everyday people and the accumulated changes they ushered in over the Sixties. He implores us to look beyond the dramatic moments, like the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre, to see how a cohort of Catholics that spanned the political spectrum contributed to significant shifts in Mexican popular, social, and political cultures.

In particular, the media and culture industries—composed in part by Catholic writers, journalists, filmmakers, musicians, fans, and interlocutors—built “shifting, less authoritarian, and even radical understandings of gender and sexuality,” even while the Mexican state remained “authoritarian, economically violent, and repressive in the aftermath of the Sixties.” Pensado shows how a focus on the State and its repressive apparatuses obscures the very real social and cultural changes that Mexico experienced. In other words, fixations on victories and defeats blind us to how profoundly Mexico and Mexicans culturally and socially opened to the world, setting the groundwork for incremental democratization over the 1980s and 1990s.

Of parallel importance, Pensado marries two branches of scholarship to explore the intersection of religion and society. He shifts back and forth, side to side, illuminating social, cultural, and political engagement by the Catholic left, the Catholic far-right, and the Catholic traditionalists who remained uneasy with Sixties (counter)culture but who were willing and eager to dialogue with the modern world. In doing so, he melds a secular scholarship about the Latin American left that often portrays the Catholic Church as a conservative monolith and a Catholic institutional scholarship that focuses on Church authorities and initiatives, often overlooking the diversity and ferment within the Catholic laity and the cultural field.

Engaging with histories of Catholics and Catholicism is a new foray for Pensado. Yet, his focus on Catholic laity and religious men and women and the many different Catholicisms—rather than hierarchy—they embodied is a strength of his analysis, which infuses the tumultuous Sixties with questions of religion and faith. This is not to say that Pensado ignores the hierarchy. Rather, he shows how Catholics responded to institutional developments and changes in ways that shaped their engagement with the world.

Of particular note is, of course, the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), which “opened” the Catholic Church to the modern world. Perhaps even more important was the formation of CELAM (1955), the Episcopal Conference of Latin America, and its associated organizations and networks that brought Catholics across the continent together in new forms of collaboration. For Catholic intellectuals, writers, and activists, CELAM was one venue through which their world internationalized, paralleling the secular internationalization of domestic and foreign politics that saw Mexico engage with the world in new ways during the Cold War.

Through this combination of factors, Pensado brings us into the everyday actions of Mexican Catholics muddling their way through a more complicated and increasingly internationalized world than the one they faced in previous decades. Their activism contributed to significantly changing Mexican culture to be more open, more tolerant, and more cosmopolitan, despite still having to wait decades for democratization.

Eben Levey is Assistant Professor of History at Alfred University. His current book project explores the intersections between Liberation Theology and the rise of Indigenous rights movements in Mexico during and after the Cold War.