This is a co-publication with Revista Común. Leer este artículo en español.

Translated from Spanish by NACLA.

The June 2 elections consolidated a political and symbolic system change in Mexico. In the presidential race, Claudia Sheinbaum of the National Regeneration Movement (Morena) won nearly 60 percent of the vote, twice the percentage garnered by opposition candidate Xóchitl Gálvez of the National Action Party (PAN). Thirteen years after its creation, Morena—founded in 2011 and since headed by outgoing president Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO)—will now control 23 state governorships, 243 seats in Congress, and 60 seats in the Senate (or 365 Congress seats and 83 Senate seats, counting Morena allies).

Morena’s overwhelming victory gives new impetus to Morena’s meteoric growth. Nourished by AMLO's leadership, combined with the skillful performance of the party’s most prominent members and the arrival to its ranks of figures, groups, and interests previously aligned with other political parties now in decline, Morena represents today the definitive force in the Mexican political landscape.

The election results also represent the collapse of the discursive and narrative regime of the so-called “democratic transition.” Since the mid-1990s, this formulation was used to refer to the horizon defined by the defeat of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which had dominated national politics for more than 70 years. Understood as an eminently political shift, this transition introduced a multiparty system and the ideals and institutions of liberal democracy, shaping the contours of public life in Mexico for nearly three decades. Yet this transition sidelined concerns about inequality, violence, and corruption that defined the governments that alternated power from 2000 onward.

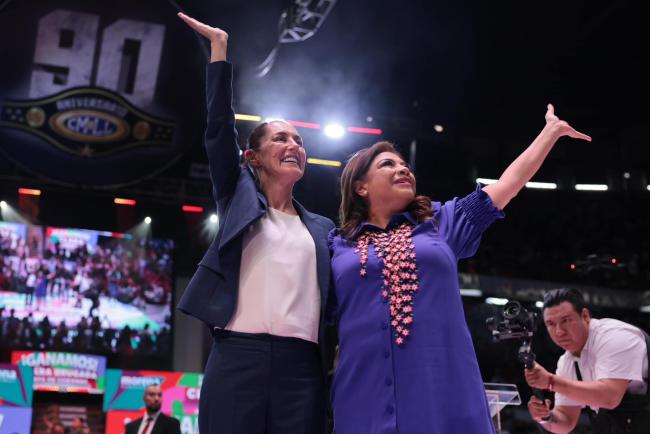

This latest election solidifies the strong support for Morena’s political project of the Fourth Transformation (4T), a reorganization of Mexican society mirroring major transformational moments in history, including Independence, the reformation, and the Mexican Revolution. It also consolidates Sheinbaum—a politician forged within Morena, a representative of the movement’s push for renewal, and the most visible face of a political generation formed outside the PRI in leftist movements since the 1980s—as a national leader.

Sheinbaum’s victory thus represents an important step toward the consolidation of a new political system in Mexico. Fed by the positive results of AMLO’s government and the ineffectiveness of the opposition, Sheinbaum’s triumph marks a profound reconfiguration of political forces and the eclipse of old terms of debate and horizons of transformation that had defined Mexican public life since the 1990s. Powerful yet contradictory, the political project headed by Sheinbaum constitutes a dam against the rise of the far right, punitive populism, and the lack of reason taking root in other Latin American countries.

“For the Good of All, the Poor First”

Various factors help explain the undeniable popular support enjoyed by the current government and the next president. In general terms, the greatest achievements of AMLO's administration have been the results of a series of reforms and policies that have reduced poverty rates for the first time in four decades and increased the net income of the most vulnerable. Since 2019, the minimum wage has consistently increased and direct transfer social programs and wealth redistribution policies have expanded. In addition, large publicly funded infrastructure works have been deployed mostly in the southern and southeastern regions, areas forgotten during decades of neoliberal development.

Together, these initiatives have increased the income levels of millions of people. They have also incorporated state-sponsored development flows into regions, communities, and social sectors that were seen as irrelevant and dispensable in the projects of previous ruling elites.

This reality is mixed with the sensation that Morena, far from being one more element of the deteriorated and discredited particracy consolidated under the guise of the “transition,” represents a different kind of political force, with a clear political project and vision. Sheinbaum and Gálvez’s campaigns represented a symbolic ordering between, on the one hand, a project for the social majorities, represented in AMLO’s motto “For the good of all, the poor first,” and, on the other, the corrupt elites that sought to reverse social progress to enrich themselves as they did in the past. Although this narrative does not completely match reality—during AMLO's government the country's billionaires doubled their wealth, according to OXFAM—the vast majority of voters embraced the Morena platform.

Pragmatic Flexibility and New Leadership

Within the ruling bloc, this break with the past was reflected in the skillful way that Morena’s internal conflicts were neutralized in the process of selecting the party’s main candidates. Despite opposition commentators’ ill-intentioned predictions that the party would collapse due to its lack of internal institutionalization, Morena’s main figures acted with enormous discipline, undoubtedly fueled by the strength of AMLO's leadership. Most of its members and structures demonstrated a great capacity for pragmatic adaptation to incorporate internal dissent and disagreements.

Beyond the internal election process that led to Sheinbaum’s candidacy, the selection of Clara Brugada to run for mayor of Mexico City was a wise choice. Another woman politically formed in the tradition of the urban popular left, Brugada will head the city that is a historical bastion of the left and that today feeds the ranks of the Morena party.

The choice of Brugada as the candidate for Mexico City did not obey a pragmatic logic. Her internal rival, Omar García Harfuch, showed signs of having a greater possibility of winning in the mayoral race. Yet the selection of Brugada showed a clear willingness not to alienate Morena’s social bases in the capital, even as Sheinbaum supported García Harfuch's candidacy. In this and other far-reaching decisions, the party has shown flexibility, cohesion, and strength.

Despite his centrality in the movement and the party, AMLO seems to have effectively stepped back, opening space for the consolidation of new leaders, starting with Sheinbaum. Likewise, the movement has large cadres of officials and operators trained in the government, both federal and in Mexico City, which has allowed for a generational turnover uncommon within Latin American leftist parties. The next test that Morena will have to face after its election win is the party congress to be held in September 2024, in which it will renew its local and national leadership.

Symbolic and Narrative Renewal

Beyond the dominance of Morena in all spheres of Mexican politics, the most significant triumph of the 4T has been symbolic. Contrary to what is argued in critical opposition circles, especially from the left, this is no minor achievement. By directly confronting the ideas, practices, modes, and representatives of the political system of the last two decades, the 4T invokes political practices and ideals that present a buffer both against attempts to restore old arrangements repudiated by the population, and against the growth of ultra-right forces like those that have flourished in other countries in recent years. Hence, Morena’s victory can be read as the closing of the historical project of the so-called “transition regime” headed by the PAN, PRI, and PRD.

The success of the new 4T narrative works on multiple levels. First, during the last six years, it has displaced from the center of public debate the political figures, groups, and intellectuals who defended a model of elitist liberal democracy that had shaped public debate and partisan political action since the mid-1990s. This has had important effects on the collapse of the legitimacy of newspapers, television stations, and magazines that until a few years ago monopolized the common sense of post-“transition” political life. On another level, this has manifested in the ideological breakdown of the old 20th century political parties, whose leaders and cadres now seem totally devoid of ideas, initiatives, and prospects.

Finally, this narrative has also served to mobilize, incorporate, and politicize millions of citizens who until a few years ago remained on the margins of national political life. Taken together, these threads of symbolic and narrative renewal pose a profound transformation that will mark the political life of the country for decades, forcing the reformation of the party system beyond the old road maps of the “transition.”

As long as this shift goes unacknowledged in the ranks of the opposition, an electoral defeat of Morena seems difficult in the coming years. In historical terms, it seems unquestionable that we are witnessing the moment of consolidation of a new era whose outcome is still uncertain but which will be difficult to reverse.

In political terms, this electoral triumph also expresses the maturing of civil society, which until now had not been able to consolidate itself as a political body that saw the vote as a reliable tool for political resolution. Victim to the survival of the old corporative regime, fraud, and electoral institutions, Mexican civil society even in 2018 did not have the certainty that the mandate of the majorities would be respected. This is a definitive mark of the current political moment in Mexico: people went out determined to vote under the certainty that the election would be the determining factor to give continuity—or not—to the 4T project.

Missteps and Mistakes

Sheinbaum also faces a horizon marked by the mistakes and weaknesses of López Obrador's project. Of particular concern is the enormous empowerment of the Armed Forces during AMLO's administration, as well as his refusal to account for the crimes committed by members of the Army and Navy from the time of the so-called dirty war to the present.

Perhaps the most painful wound of this six-year term is the resounding failure of official efforts to provide certainty and justice to the victims of the state repression of previous decades as well as to the thousands of families of the disappeared. The disappearance crisis, a result of the violence that has plagued the country since the declaration of the war on drugs in 2006, is synthesized in the emblematic case of the 2014 disappearance of the 43 Ayotzinapa students. AMLO will leave office with that case still pending. The new president will have to deal with that failure and with the decisive role that the Armed Forces play today in the government apparatus she inherits.

The administration’s complex relationship with the social left, which will surely confront the government in the search of answers to its demands, will be a barometer of the extent to which both the party and the government maintain an active commitment to representing the interests of Mexico’s poorest citizens.

There are other outstanding issues that affect the daily lives of millions of Mexicans and that the new government will have to address as a priority. First, it would be dangerous if triumphalism prevents Morena from taking seriously the need to think of new strategies to deal with the continuous expansion of the territorial, armed, and economic power of organized crime, whose networks continue to grow and mutate month by month throughout the country. Another potential danger lies in the empowerment of parasitic and harmful characters and political groups, such as the Green Ecologist Party of Mexico (Verde), a grouping that represents the worst vices of the outdated particracy, but which under the shelter of Morena’s alliance is now the second largest force in the Mexican Congress.

Finally, it is impossible to postpone any longer the creation of a national strategy to adequately address the already visible and dramatic ravages of the global climate catastrophe. One of the great mistakes of AMLO's administration—and one that will undoubtedly weigh heavily on the historical judgment of his government in the future—has been his government's blindness to the vulnerability in which the climate catastrophe is already leaving millions of people across the length and breadth of Mexico.

U.S. Relations and the Rise of the Global Far Right

An ever-present challenge for Mexico's governments is the relationship with its northern neighbor. But in particular, as both countries hold presidential elections this year, the outlook for Sheinbaum will be especially challenging in the event of a Republican triumph that reinstalls Donald Trump in the White House. Each country is the other's top trading partner, and, sharing the world's busiest border in trade terms, both governments will have to navigate, together with Canada, a review of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada agreement (known as T-MEC in Mexico) in 2026.

The two countries also jointly face the constant movement of migrants to the north. This all comes in a convulsive geopolitical scenario marked by the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian conflict and the genocide in Gaza. Already in her first speech, the president-elect vowed for a respectful relationship between neighbors. Yet she added that Mexico should turn southward, adhering to the principle that an active and sovereign international policy is the most appropriate way to deal with Mexico’s asymmetrical relationship with the United States.

Morena’s historic triumph also raises dangers on the political front. As has happened in other Latin American countries and in Europe, a new reactionary far right could take shape in Mexico, nourished by the collapse of traditional conservative parties. In the context of an eventual erosion of the 4T project, it is only a matter of time before a renewed right-wing front emerges in the country. Unlike other countries such as Argentina, Ecuador, and El Salvador, where the decline of the old ruling classes gave way to the emergence of destructive ultra-right alternatives, in Mexico the 4T still has the advantage of representing in its project a viable alternative to the deterioration of and discontent with the neoliberal regime.

Beyond the criticisms—which should not cease throughout Claudia Sheinbaum's six-year term—it must be recognized that, in the present Latin American and global context, the 4T represents a project that is important to defend insofar as it constitutes a barrier against the advance of the ultra-right, of punitive populism, and of the absurdity of governments such as that of Nayib Bukele, Javier Milei, or Dina Boluarte.

Daniel Kent Carrasco, Diego Bautista Páez, Diana Fuentes and Francisco Quijano are members of the editorial board at Revista Común.