Leer este artículo en español.

The government of Javier Milei failed to pass its most ambitious bill to date through Congress in February. Known as Ley Ómnibus, the Law of Bases and Starting Points for the Freedom of Argentinians proposed fiscal reforms, the privatization of state-owned companies, the delegation of extraordinary powers to the president, and electoral reforms, among several other axes.

Furious with his first major political defeat since taking office, Milei publicly accused provincial governors and congressmen of betraying him in the vote, calling them “criminals” and "extortionists."

Some politicians and outlets rushed to blame the president and his cabinet’s inexperience and improvisation for the law’s failure to pass. This narrative, however, is potentially misleading. Milei’s law may not have faltered by chance at all. It may make more sense to view its failed status as a deliberate outcome of the president’s actions: Milei systematically weakened his own bill and later strategically positioned its failure as a convenient scapegoat for blaming the very caste he despises. Now he has taken the bill and used it as a tool to again blame the country’s politically established elite for the dire state of the Argentine socioeconomic reality, with the highest inflation in the world recorded in 2023 and 57.4 percent of its inhabitants under the poverty line.

Bound for Legislative Defeat

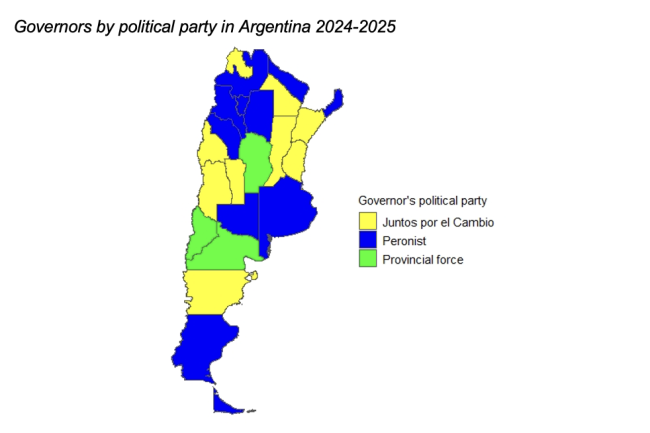

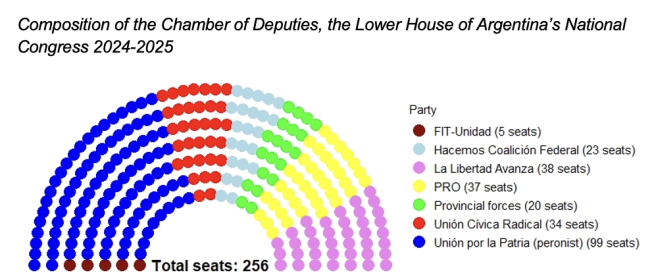

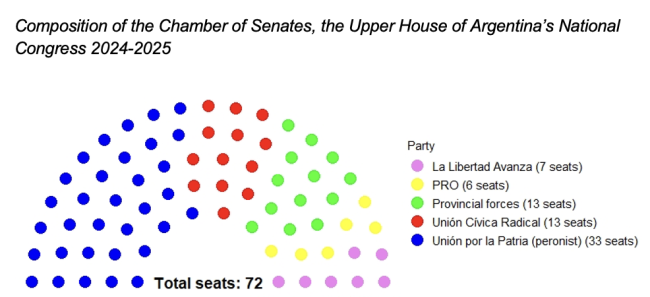

At the outset of his term, Milei’s force in Congress went up by 38 seats, totaling 78 out of 257 seats; and 13 senators out of 72. This was, in large part, thanks to his alliance with the former Argentine President Mauricio Macri and the Propuesta Republicana (PRO) party president and former presidential candidate and now Minister of Security Patricia Bullrich. However, this was still not enough for Milei to achieve the parliamentary majority required to validate a bill presented in Congress. Milei then had to make agreements with legislators from other parties, forcing him to negotiate his Law with the infamous casta. Both the Lower Chamber (Diputados) and the Upper Chamber (Senado) are responsible for approving or rejecting laws, including those proposed by the president. Milei faces not only one but two legislative barriers. At the same time, the Peronist party has 11 governors, the Juntos por el Cambio (JxC) coalition (between PRO, Unión Civil Radical (UCR) and the Civic Coalition has 10 governors), and the remaining three correspond to provincial forces which are political forces that are limited to their provinces. The lack of governors from Milei’s La Libertad Avanza (LLA) party is a considerable obstacle. In Argentina, governors usually have considerable influence on how Congress representatives vote. Without any agreement with the governors, obtaining parliamentary support becomes even more of a challenge for Milei.

Milei needed at least 129 votes to pass his Ley Omnibus. Obtaining those votes meant negotiations with the historic centrist UCR party, representing the non-Kirchnerist branch of Peronism, and the remaining provincial forces; the so-called “oposición dialoguista” (pro-dialogue opposition).

Despite his insistence on how crucial the Ley Omnibus was for the success of his government plan and the freedom of Argentine society, Milei became his own biggest obstacle. From the beginning of negotiations, he showcased erratic behavior on social media, criticizing the pro-dialogue opposition. He consistently undercut Interior Minister Guillermo Francos who was in charge of leading negotiations with the governors and the congressmen. While Francos took a more conversational approach, Milei opted to confront governors and the pro-dialogue opposition and undermine Franco’s authority. Milei also kicked out his Minister of Infrastructure for leaking to the media that Milei allegedly threatened to “ruin [the governors] financially.”

What is particularly disorienting about Milei’s behavior is that he had the opportunity to gather the necessary votes for Ley Omnibus; initially, Congress approved the law by 144 to 109. However, his all or nothing, zero-sum negotiations approach showed its disastrous results during the particular vote session when Congress had to vote on each individual article.

The debate originally projected to last for days finished only after a few hours. Milei’s government arrived at the session without sufficient votes, and the opposition began to reject Ley Omnibus article by article. By the time they reached Article 6, the opposition parties adjourned the session and asked the government authorities to keep negotiating. This request was then denied by the government which proceeded to end the session. This outcome presented the first time in Argentine history that a government’s first law proposal was rejected. In the words of the opposition: “The Ley Omnibus is politically dead.” Milei, however, would use this loss as part of his plan.

All Out Against His Political Opponents

Within minutes of Ley Omnibus’s defeat, Milei turned over to X, where he took aim at the "caste” and implied that the pro-dialogue governors and congressmen were individuals who “destroyed the country.” He then shared a list of those who voted in favor and against the law—calling the latter “enemies of a better Argentina,” and suggested the possibility of submitting the law to a referendum.

Milei did not stop there. Two days later, he eliminated subsidies that the national state provided to the provinces' public transportation systems. Currently, his administration is withholding the transfer of resources for public school teacher salaries. These two measures, coupled with the decreased tax revenue in provinces due to the economic slowdown and an increasing social climate of discontent, are creating a difficult terrain for provincial governors to navigate. Consequently, the 24 provincial governors have elevated their joint concerns to the president.

In confrontational fashion, Milei is speaking out against governors without partisan distinction, ranging from Peronist governors such as Axel Kicillof of Buenos Aires and Ricardo Quintela of La Rioja, to pro-dialogue governors Martín Llaryora from Cordoba, Maximiliano Pullaro from Santa Fe, and Ignacio Torres from Chubut.

It would be far more strategic to cut funding to Kirchnerist Peronist provinces while allocating more resources to the pro-dialogue opposition. This has been the strategy for most governments since the return of democracy: carrots to their allies, sticks to their opponents. What then is the logic behind Milei’s actions?

All Eyes Set on 2025

If Milei has demonstrated anything since first appearing in the political landscape, it is that he does not play by others’ rules. Rather, he creates his own. Behind Milei’s sabotaging the law lies a logic that cannot be explained without going back to the discourse that supports his endeavor: the religious battle against the caste.

Milei’s whole image has been built around a logic of friend versus enemy, the good versus the bad. The president itself has described his party, political allies, and voters as “the forces of heaven.'' In Milei’s view, his heavenly forces are battling a political caste that presents itself as an ever-lasting enemy and the alleged root of the cause of all problems in Argentina. But what exactly is the caste? In short, whatever Milei wants it to be. The political caste that “impoverishes” and “ruins” Argentinians includes many actors: corrupt politicians, labor unions, state-owned and privately-owned media, and businessmen, among others.

The idea of the caste legitimizes Milei’s government plan: his actions will be supported as long as they target it because the caste is what withholds progress for Argentineans. If the caste can be anything, and if the electorate will support the actions against the caste, why not also include pro-dialog governors and congressmen in its definition? This is what Milei attempted with the Ley Omnibus defeat. Rather than accepting any blame for his brute negotiation tactics, he blamed anyone who could fall under his personal definition of the caste.

The explanation behind the expansion of the caste’s definition so it involves the pro-dialogue parties perhaps lies in the upcoming 2025 legislative elections. There are at least two ways the president can generate the political cohesion necessary to make implementing changes easier. The first path is to negotiate with the pro-dialogue opposition. The second option is to undermine the political force of the centrist parties by polarizing the Kirchnerist Peronist coalition Unión por la Patria by trying to radicalize the votes from non-Kirchnerist parties that support Milei in the ballotage. Although with the latter, the administration would not have to make concessions in its strategy if it were to succeed.

Milei has already started down this second path, evidenced by his PRO alliance. The most difficult battle, however, will be winning the center parties’ electorate. This sounds paradoxical, but in Milei’s mind it is extremely rational: you can either be with the “good Argentineans” or the caste. There is no middle ground. With this enemy-friend division, Milei will attempt to polarize the Argentine electorate for the upcoming 2025 elections.

If Milei arrives at the 2025 legislative elections with an inflation decrease, a GDP growth forecast as predicted by the IMF, and a polarized electorate, the elections will give him the much-needed parliamentary force to approve legislation like the Ley Omnibus without having to make concessions.

A potential agreement?

In his first Ordinary Session Opens speech, Milei outlined the current state of the fiscal, debt, and monetary crises using his efficacious anti-caste narrative. Milei suggested putting disagreements aside and cooperating for the betterment of Argentina. He urged all governors to sign the "Pacto de mayo" (May Pact) in the province of Córdoba on May 25 (the day on which the first national government in Argentina is commemorated).

He then raised two conditions: the adoption of a revised omnibus law and mega-decree that aims to alter laws that impact the microeconomy. Despite claiming that this accord was the result of an agreement rather than a "consensus," he included 10 irrevocable points that are comparable to the Washington Consensus: fiscal expenditure reduction, tax reforms, fiscal balance, deregulation, openness to international trade, legal security for private property, or liberalization of foreign direct investment (mainly in natural resources). This is not casual; the Washington Consensus refers to two ideas that represent economic prosperity for Milei: Liberalism and Menemism.

Many questions remain regarding Milei’s strategy: Will the May Pact occur? Will the governors adapt to Milei’s rule, or will they force the president to adapt to the already established political caste? How will Peronist governors react? Is this May Pact an end in itself, or a means to reveal with whom Milei’s government can dialogue and cooperate? Despite these uncertainties, two aspects remain clear. First, to govern Argentina, it is essential to reach some level of consensus with provincial governors. Second, the president needs to extend his legislative coalition to enact his policy plans. Until then, it remains uncertain to what extent Milei will be able to achieve his objectives.

Francisco Olivero is an MSc candidate in Applied Economics at the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella, and holds a B.A. in Political Science from the same institution. His research interests include the political economy and democratic backsliding in Latin America.

Salvador Lescano is a research intern at InSight Crime, a freelance writer, and a research assistant. He holds a B.A. in International Relations from Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. His articles on Argentine politics have been featured in several outlets such as The Diplomat, NACLA, and Global Americans, among others.