On August 3 a group of miners in Sabinas, a small city in Mexico’s northern state of Coahuila, went to work. Everyone knew that conditions were dangerous, that the mine bordered an abandoned pit filled with water. According to testimony, the workers warned of a possible leak a few days before. Rather than halt operations, the operators of the mine offered nominal additional pay. Not much beyond the usual wage, which was about $150 Mexican pesos ($7.46) per ton of coal, split between partners. But enough to encourage workers from other mines to come to El Pinabete. Because in Coahuila, the main industry is mining, and nobody gets paid for days they don’t work.

The workers entered the 60-meter deep mine and began extracting coal. That afternoon, they breached the area filled with water. The walls caved in and the mine flooded. Some people nearby, having heard a loud sound, rushed to the mine to help. They lowered ropes, trying to pull out the workers. Of the 15, five managed to escape. Nearly a month later, following several failed rescue efforts, the remaining 10 are still there. There is no longer hope that they will be found alive.

Over 60 percent of Mexico’s mining accidents occur in Coahuila, the state known as Mexico’s región carbonífera, or coal region. Last summer, two separate cave-ins killed nine miners. In 2011, an explosion killed 14. In 2006, the worst mining accident in the country’s history took the lives of 65 people in the Pasta de Conchos mine. Only two of the bodies have been recovered. Most accidents happen in Sabinas, a city of some 60,000 people, because of its abundant coal deposits

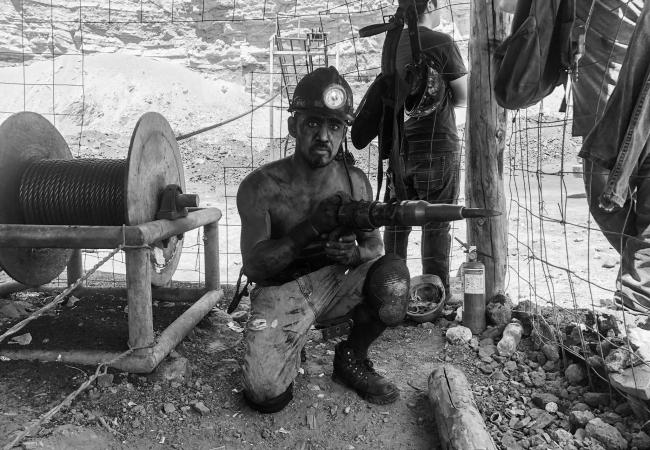

The Pasta de Conchos accident led to the formation of the Organización Familia Pasta de Conchos (Pasta de Conchos Family Organization), a group dedicated to fighting for the rights of miners in Coahuila. It is one of the few organizations representing the workers, who face a particularly high risk environment due to the nature of the state’s coal sector. According to Omar Ballesteros, a representative of the organization, Coahuila’s mines are largely informal, operating with a lack of accountability and adequate safety measures. “The only safety equipment miners get is a helmet and a flashlight,” he says, “the workers aren’t even given water to drink.” Employees are rarely registered with social security, and children as young as 14 work in the mines. While Mexico’s Ministry of Labor claimed there had been no complaints about the mine since it began operating in January of this year, there have also been no inspections.

Despite the dangers associated with the mines, workers say it is still preferable to being employed in a factory where the wagers are even lower, at about $60 Mexican pesos an hour ($3.00), and the hours are long and inflexible. Coahuila has been celebrated as a center of job creation, where companies such as General Motors produce auto parts and Coca Cola bottles its products. Like other states in northern Mexico, Coahuila is an industrial center. But, residents say, job creation for its own sake should not be celebrated.

Coahuila’s Long History of Mining Accidents

Abuses associated with Coahuila’s mining sector are nothing new. Under the reign of the dictatorial President Porfirio Diaz (1876-1911), the country’s coal sector boomed. The expansion of the U.S. railroad led to a continuous need for coal, and companies flocked to Mexico to meet the demand. A massive labor base, made up primarily of poor peasants, soon followed. The surplus of labor led to the abuse of workers by coal companies. Major mining companies, primarily from the United States, built entire cities around the mines. They provided employees not with a salary, but with coupons to exchange for goods that could only be purchased at stores run by the company.

While the Mexican revolution eventually disrupted the industry, it quickly bounced back. During the Partido Revolucionario Institucional’s (PRI) 50-year reign of power, the party largely controlled the mines and associated unions, feeding labor leaders a steady stream of bribes in exchange for their voting power and complicity. Rather than representing workers’ rights, union leaders pacified employees while pocketing a portion of union dues. During the liberalization period of the early 1990s under President Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1988-1994), the sector was disrupted but the abuses continued. Nationalized companies were split and sold to private interests, leaving countless workers desperate and unemployed. While some sought work with major coal companies, most ended up working in small mines, many of which were owned and operated by local politicians who were eager to maintain their grip on the industry.

Today, Coahuila is one of the few states still governed by the PRI, and this old political guard still largely controls the coal mining sector. “The same businessmen always end up in the same political position,” said Ballesteros, “and they have controlled the narrative around the accidents and death and disasters in the coal mines for a very long time. Most of the mines’ owners have a political position or a political link. The wealth always stays in the same circles.”

Accountability Remains Elusive

Following the collapse at El Pinabete, rumors began circulating about who was responsible for the accident. The name immediately put forward was Cristian Solis Arriaga, the registered owner. But residents of Sabinas know Solis Arriaga, and few believed that this 27-year-old man without property, whose wife makes money through Facebook raffles, held contracts worth $50 million Mexican pesos.

He was, however, the individual sent to register the workers for social security after the accident already happened. Arriaga’s name was tied to the mine, and he will therefore be investigated by the Attorney General. But others in Sabinas put forward two other names: former mayor Régulo Zapata Jaime and his son Régulo Zapata Morales. Both are associated with the company Carboneros AJ, which provides coal to the state owned electricity company, the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE.)

This kind of obfuscation is not uncommon, Ballesteros said. “Most of the mines are informal. They have an owner, a concessionaire, but they also use fronts. So whoever appears as the owner isn’t actually the owner. The system is extremely perverse.”

This mechanism allows those who hold mining concessions to hide behind the registered owners, typically front men with little actual power. It also permits the CFE to buy from these mines without addressing the labor abuse and dangerous conditions associated with them. According to Ballesteros, “the type of coal that the CFE buys is the most dangerous, coming from the mines that are the most informal and that operate with the most irregularities.”

The Legacy of Pasta de Conchos

The Pasta de Conchos mine exploded due to an accumulation of methane gas. According to reports, the accident could have been avoided. In the years prior to the accident, the mine recorded significant safety hazards, with 43 violations reported during its last inspection. Grupo México, the company that owned the mine, never addressed the issues.

When President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador was elected in 2018, he and his Morena party were largely considered a symbol of change, a transformation from prior periods of nearly unchallenged PRI rule. As part of his campaign, he promised to finally excavate the 63 bodies still buried in the Pasta de Conchos mine. Nearly four years into his term, the excavation has yet to begin. Instead, the administration has focused largely on symbolic gestures. “The current government is paying more attention to building a monument, “Ballesteros said. “That’s not what we want. We want the bodies to be recovered, the remains of our loved ones.”

In June, when the monument’s construction began, the Organización Familia Pasta de Conchos asked that it be halted until the bodies were excavated, claiming that they don’t need a memorial to remember the tragedy. They have been searching for justice for 17 years, and the company has never been held accountable.

More than a memorial, the organization demands that the events in the Pasta de Conchos mine never be repeated, that the conditions for safe employment be created. Less than two months after construction of the memorial started, and after the organization echoed its refrain calling for improved conditions in the mines, 10 more miners were trapped below ground due to an avoidable accident. According to the organization, both the federal and state government only appear concerned with miners' safety after an accident has occurred. “There is no justification on the part of the state for doing nothing,” Ballesteros said. “We’ve seen it in past terms. Everything just stays the same.”

While the government has scarcely budged in its moves to protect workers’ rights, the Organización has still made progress. After years of struggling to achieve justice in Mexico, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IAHCR) accepted the Pasta de Conchos case in 2018. The IAHCR report demonstrates what the organization has been fighting to convey: that the Mexican state is complicit in the miners’ deaths for failing to force companies to respect worker rights to safety. The group’s ongoing goal, according to Ballesteros, is “to be able to make visible what is happening, mainly to show that coal is irremediably sacrificing many miners and that the 3,000 deaths that we have documented have never been punished. An individual has never been held responsible. A coal businessman has never been put in jail.”

For members of the Family Organization, “this episode ruptured their family and community dynamics, creating an unfillable gap that remains to this day. In addition to the painful absence of their loved ones, they feel the pain of not being able to offer a dignified burial to their fathers, brothers, friends, and husbands who are still beneath the earth.” Now that trauma is being repeated: following a series of failed rescue efforts, hopes of finding the Coahuila miners alive have faded.

Now, rescue teams have shifted their focus towards retrieving the remains, a process that could take a year or more. The Organización Familia Pasta de Conchos criticized the federal government’s excavation plan, which involves removing some 5 million tons of earth, for its unrealistic approach and the lack of consultation with local rescue teams or coal mine experts. Some of the miners’ family members have also expressed discontent, arguing that the compensation offered is inadequate. Instead, some demand that the land on which the mine sits be transferred to the families, both as a form of reparation and to guarantee that coal will never be mined at the site again. The federal government has also promised to build a memorial—yet another reminder of the state’s failures to provide residents of Coahuila with employment opportunities that do not put their health and lives at risk.

Next summer, Coahuila will hold gubernatorial elections. It is possible that the PRI stronghold will be won by Morena, the party of change. But even if a transfer of power takes place, it is possible that politicians will have already forgotten about this latest mining tragedy. The Organización Familia Pasta de Conchos will continue to fight to ensure that doesn’t happen. “As always,” Ballesteros said, “the ones who are sacrificed are the miners. To the bosses and the politicians, they are 10 miners, nothing more. They are just symbols. But to us, they are 10 sons, 10 brothers, 10 cousins. They are our neighbors.”

Chelsea Carrick is a freelance writer based in Mexico City, where she writes about politics in Latin America. She holds a Master's Degree in Political Science from the CUNY Graduate Center.