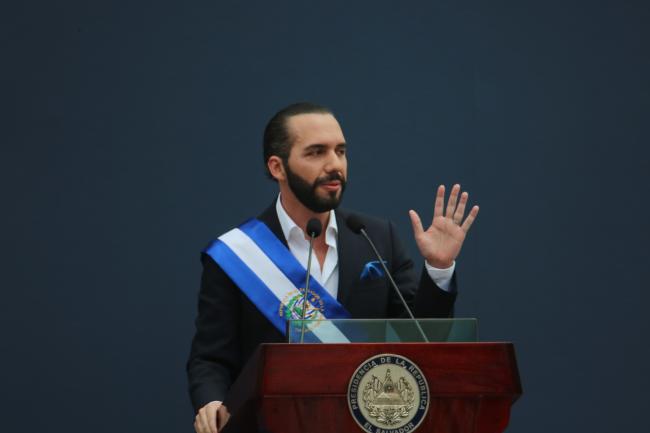

On September 19, 2023, during the 78th Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations, Nayib Bukele sung the praises of his government, boasting El Salvador’s transformation from the “murder capital of the world” into the “safest country in Latin America.” A year and a half into a state of exception characterized by widespread arbitrary detention and other human rights abuses, Bukele claimed that his “recipe” for success was breaking from established strategies. He advised other countries to “make their own decisions” and have the “bravery” to forge ahead despite criticism.

“For decades, we tried everything that others said was best for us,” he said. “They made us fight a civil war for a cause foreign to our reality [referring to the Cold War].... They made us sign false peace agreements, which had nothing of peace, and which only served to allow the two sides in the war to share the spoils.”

He continued: “We tried every formula they gave us, and nothing worked. Then, protected by foreign powers, we handed the country over to the Right. And then, also protected by external agents, we gave power to the Left. This is how they kept us during 30 post-war years, during which there were more deaths than in the civil war, and more poverty and more violence. Nobody did anything to fundamentally change either the system or the institutions, much less the laws.”

Since launching his bid for the presidency, Bukele has defined himself in contrast to El Salvador’s two traditional political parties, the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). On the campaign trail, he railed against los mismos de siempre—the “same old” politicians. But since entering office, another narrative has taken increasing precedence: his attacks on the 1992 peace accords that ended 12 years of armed conflict. Nayib Bukele has been waging war against the past. In the leadup to his 2024 run for reelection, his political project depends on it.

Bukele won the 2019 presidential election on a platform that positioned him as a new kind of politician who did not represent the corruption, incompetence, and political failures of his predecessors. On the first day of his administration, he said that “together” Salvadorans were beginning a new history. He announced that he was going to need the support of the people for the times that were coming, and for the “difficult decisions” he was going to take.

Since then, he has continued to direct an antagonistic and hostile attitude against the political establishment that emerged out of the civil war and governed the country for the next three decades.

ARENA and FMLN were the protagonists in El Salvador’s violent and protracted armed conflict. Insurgent leftist organizations, mostly formed in the 1970s, joined together in 1980 to create the FMLN guerrilla army. Their goal was to seize control of the state. The FMLN argued they were the standard-bearers of the masses fighting against the abuses and repression of the Salvadoran state.

ARENA was founded as a political party in 1981 by the infamous military officer Roberto D’Aubuisson, the most notorious symbol of the death squads at the time and later named in the UN-backed truth commission as having ordered the 1980 assassination of Archbishop Óscar Arnulfo Romero. Several U.S. officials saw D’Aubuisson as the figure that ran El Salvador until his 1992 death. ARENA’s motto was to defend the homeland from the communist threat and unite the interests of the economic elites—namely the protection of their property rights and a rejection of land reform—with those of the military.

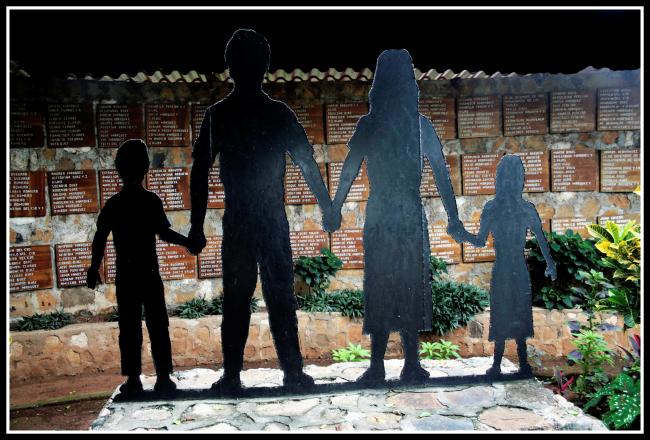

The war brought intense government repression and severe human rights abuses at the hands of the military, supported by the U.S. government to the tune of $1 million per day at the height of the conflict. Approximately 75,000 people were killed and more than one million displaced, both within the country and as refugees to Central America, Mexico, and the United States.

By the end of the bloody 1980s, a stalemate between the FMLN and the U.S.-supported Salvadoran regime gave way to negotiations between President Alfredo Cristiani’s government (1989-1994) and the FMLN to put an end to the conflict. The UN-mediated Chapultepec Peace Accords—signed in Mexico City on January 16, 1992—agreed on the elimination of the repressive apparatus of the state, introduced changes in both the judicial and electoral system, officially recognized human rights, and allowed the FMLN to transition into a legal political party. Despite the limitations of the agreement and very real shortcomings in the implementation of the promise of peace, the accords secured an end to armed conflict, creating the grounds for democracy.

Yet nearly three decades after the accords were signed, Bukele exploited the worst abuses of the civil war to double down on his hostility towards ARENA and the FMLN. In a December 2020 speech in El Mozote—where in 1981 a U.S.-trained army battalion slaughtered nearly 1,000 civilians, more than half of them children—he accused former presidents of the Left and Right of using the El Mozote massacre for political ends. He called the civil war and Chapultepec Peace Accords a farce, an agreement between two corrupt sides.

Later, in January 2022, the Legislative Assembly—where supporters of Bukele had secured a supermajority—passed a resolution that eliminated the national commemoration of January 16 as the day the accords were signed. Instead, the Assembly recognized January 16 as “the national day of the victims of the armed conflict.”

But as Jorge Guzmán argued, these words and actions completely disregarded the victims. “Only those who lived and suffered the war firsthand can assess the true dimensions of the silencing of the weapons and the end of persecution,” he wrote. In 2016, when El Salvador’s Supreme Court overturned a 1993 amnesty law that had long protected conflict-era war criminals from prosecution, Guzmán became the judge overseeing a historic trial against high-ranking military officers for the massacre at El Mozote. In 2021, he was removed from the case, which had struggled to move forward as Bukele repeatedly denied investigators access to the military archives.

In response to Bukele’s “farce” statement, Geoff Thale, president at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) at the time, argued that the comments were not surprising because they fit with Bukele’s general dismissal of Salvadoran political leaders. Salvadoran journalist Óscar Martínez agreed, noting that Bukele, who was just a child when the war ended, dismissed the memory of the war and the accords because they did not serve his political aspirations of “annulling [his political predecessors] at the polls and in the memory of Salvadorans.”

Martínez also pointed out that past politicians have neglected the “obligations” contained in the accords, leaving peace “orphaned.” Indeed, the peace agreement failed to address El Salvador’s unequal system of land tenure, the concentration of wealth, high rates of poverty, and social exclusion. The accords also left intact the economic neoliberal adjustment program underway since Cristiani came to power in the final years of the conflict. In other words, the accords, paradoxically, left intact the socioeconomic system that was one of the root causes of the civil war.

In El Salvador in the Aftermath of Peace, Ellen Moodie examines everyday accounts of individuals navigating a “stunted transition to democracy.” Moodie shows that in the accords’ aftermath, Salvadorans felt a sense of insecurity and social anxiety due to a rise in street crime, especially in the capital city of San Salvador. For Moodie, a sense of separateness replaced the imagination of obligation, or social care, that characterized memory of the war and the years leading up to it.

Amid chronic gang violence, rampant government corruption, and persistent out-migration, Bukele’s message clearly has resonated with many peoples’ experiences of the failures of the democratic transition and popular disaffection with the discredited ARENA and FMLN. Yet rather than strengthening democracy and addressing dire underlying social conditions, Bukele has chosen authoritarianism, buttressed by his attacks on historical memory.

War by other means: The memory battles

In Stories of Civil War in El Salvador: A Battle over Memory, historian Erik Ching argues that, between ARENA and the FMLN, “neither side has hegemonic control over the story of the war.” With a reign of impunity preventing truth and justice, Salvadorans have not reached a consensus or widely accepted script of the past. Instead, there has been a battle of memories versus memories: the guerrilla comandantes believed they were fighting a just war against a U.S.-backed cabal, while army officers were driven by the singular goal of promoting the survival of the military institution.

But according to Ching, “It is irrelevant if those narrators are right or wrong, honest or dishonest, forgetful or mindful.” Instead, what is most relevant is that “each of them has injected his or her version of the past into El Salvador’s postwar public sphere, and in so doing they are all participating in the contest for control over the story of the war.”

In a 2012 survey about Salvadoran attitudes towards the Peace Accords, the University Institute of Public Opinion (IUDOP) at the Central American University (UCA) in San Salvador found that two out of three Salvadorans thought that things were the same or worse than during the war. More than half of them expressed little to no satisfaction with Salvadoran democracy. Salvadoran opinions did not change much until Bukele assumed office. In IUDOP’s 2020 survey, the last year in which IUDOP asked about the Peace Accords, 45 percent of survey respondents thought that the country was better than before the Peace Accords, and half of those said that it was because there was no war anymore, there was peace.

It is possible that the fall of the FMLN and ARENA in the Salvadoran political imaginary and Bukele’s media power contributed to these shifting opinions. In 2020, homicide rates had reached historic lows, which Bukele credited to his security policies. However, as El Faro has reported, Bukele’s administration was secretly meeting with gang leaders at the time, allegedly negotiating a drop in homicides.

Since then, homicides have dropped further under Bukele’s state of exception, which has suspended basic rights and imprisoned more than 70,000 people since March 2022 in an indiscriminate crackdown on alleged gang members.

On June 1, 2023, in his speech marking four years of his administration, Bukele praised his “estado de excepción” (state of emergency), saying that El Salvador was a “different country.” He made two announcements strongly invoking his version of the country’s historical memory.

First, he presented a proposal to reorganize El Salvador’s political and administrative systems, seeking to reduce the country’s municipalities from 262 to 44, as it was before the end of the war. Second, he announced a plan to downsize the Legislative Assembly from 84 to 60 representatives, also as it was before the peace agreements accords. He accused ARENA and the FMLN of benefiting from the “farce” of the accords, allowing ARENA to maintain its privilege while giving the FMLN “su tajada del pastel" (their slice of cake).

While Bukele claimed to be correcting that injustice, many interpreted these reforms as moves to concentrate power ahead of his unconstitutional run for presidential reelection in 2024.

Even though the constitution prohibits presidential reelection, in 2021 the Supreme Court cleared the way for Bukele to run for a second term, and electoral authorities recently confirmed his candidacy. He has consistently maintained over 75 percent approval ratings and, according to a CID Gallup Poll, has the highest approval level among Latin American presidents. Almost half, 46.1 percent, of Salvadorans feel close to Bukele.

These numbers suggest that Salvadorans are tired of the past’s old stories and the lack of significant change—in security and economic and social opportunities—in the postwar period. After decades of impunity and failed promises of peace and prosperity, Salvadorans young and old may feel the need for detachment from the past to move on. Bukele takes advantage of this apathy and disaffection. His words are weapons in a war that somehow never ended, reconfiguring the past to justify his actions, especially his “estado de exepción.”

Progressive forces do not need to outdo Bukele’s narrative. His statements are a total affront to historical memory of the country and to the victims in their quest for justice. Yet it is also clear that the post-war quest for justice has failed. El Salvador must reckon with and repair the past. Bukele’s authoritarian project will carry on as long as it continues feeding on his narrative.

To have any shot at diminishing Bukele’s chances in the 2024 general elections, progressive forces need to challenge his vision and fight for a different valorization of the past. How Salvadorans decide to tell their story will undoubtedly define their future. Progressive forces need to tell a better story—a story of hope. A story that will remind Salvadorans that in spite of all the suffering and destruction, and in spite of the failures of the Peace Accords, it is worth saving the legacy of the past to protect the same democracy—however imperfect—that put Bukele in power.

Manuel Sánchez Cabrera is a PhD candidate in the Department of Romance Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The author thanks his colleague Julio Gutiérrez—PhD candidate in Anthropology at UNC-CH—for his insightful comments on earlier versions of this piece.