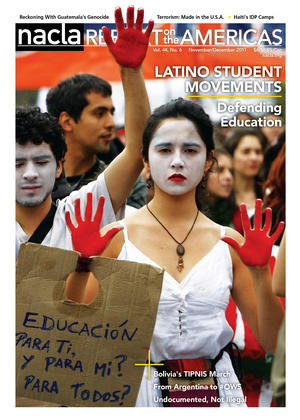

NACLA’s latest Report on the Americas is now available. This issue, "Latino Student Movements: Defending Education," gives voice to Latino student movements across the Americas that are standing up to the crises, cutbacks, and repression. The following is the introduction to the Report.

Our education is under attack! What do we do? Fight back!” chanted high school students defending their beloved Mexican American Studies program in a Tucson, Arizona, school board meeting in April. They are not the only students fighting to defend education. Almost everywhere, education is under attack, and students across the Americas are fighting back in so many places that it would be impossible to include them all in just one issue.

On October 26, 10,000 marched in the Brazilian capital, Brasilia, in defense of public education, demanding an investment of 10% of Brazilian GDP in the National Education Plan then under debate in the National Congress.1

In Colombia students have held three national marches and a monthlong strike since the beginning of October against a reform to Law 30 of Superior Education, which they say would essentially privatize the Colombian education system.

In late July and early August, students occupied over 150 high schools across Honduras in opposition to a proposed General Law on Education in the National Congress, which they fear would open the door to privatizing education.2

In perhaps the most emblematic case, in May, then Chilean minister of education Joaquín Lavín proposed an initiative to increase government funding of nontraditional universities. Students took to the street en masse, and have been there ever since, demanding free universal education and an end to the neoliberal policies from the era of dictator Augusto Pinochet, policies that valued profit over education.

Pinochet-era reforms slashed Chile’s education budget, gutted the public education system, and made it next to impossible to reform Chilean education policy. Chile’s universities are now the most expensive in Latin America. Even if they graduate (80% of Chilean university students do not), students are left with endless debts. But as political scientist J. Patrice McSherry and historian Raúl Molina Mejía explain in their article, students are not only challenging Pinochet’s legacy by standing up for education, but they are reinvigorating a powerful mass movement that is demanding a true democratization of the country.

Since the 1980s, the United States has been taking a page from the Pinochet neoliberal education playbook. Then president Ronald Reagan offered federally funded school vouchers for underprivileged youth to study at private schools (rather than investing the money into improving public schools). Voucher programs were promoted by right-wing think tanks, and former presidents George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush. Vouchers have grown exponentially over the last three decades.

However, the modern-day assault on U.S. public higher education was actually launched by Reagan long before he had been elected to the Oval Office.

“Ronald Reagan launched his political career as governor of California in 1967 by having run not so much against his popular New Deal opponent, Pat Brown, as against the students and faculty of the University of California at Berkeley,” wrote University of California (UC) Santa Barbara English professor Christopher Newfield in a 2008 exposé on the privatization of the U.S. public university.3

Once elected, Reagan attacked public higher education. He called for an end to free tuition for state college and university students, demanded annual 20% cuts in higher education funding, slashed state funding for public university capital projects, and declared that the state “should not subsidize intellectual curiosity.”4

Indeed, since the late 1970s, in the United States, student contributions as a percentage of total university income have been on the rise, from 35% to 48% in 1998. Meanwhile state and local contributions fell from over 55% to less than 43%.5 This trend has only been exacerbated in recent years, with massive budget cuts, tuition hikes, and layoffs at universities across the country in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

As in the 1960s, with the UC Berkeley Free Speech Movement and Reagan’s subsequent crackdown, California’s universities have again become the battleground over public education. In November 2009, the UC Regents passed a 32% tuition hike. Students responded by occupying campuses across the state. In his article, sociologist Zachary Levenson charts the struggle of California students against the privatization of California public universities. Spurred by the nationwide Occupy movement, and despite police repression, mobilizing is again on the rise. But, Levenson asks, will students in California be able to shut down their campuses indefinitely—like in Chile or Puerto Rico—in order to demand an end to austerity?

Across the region, occupations have become the tactic of choice for students looking to demand change. While students continue to hold marches and rallies, drawing thousands, they are also embracing other more creative and radical tactics: sit-ins, kiss-ins, street theater, and direct action. Using blogs and social media, this new generation of students are telling their own stories, rather than waiting for someone else to do it.

These creative tactics have increasingly been used by DREAM activists in the United States in their fight against deportations and for legislation that would give undocumented youth a path to citizenship. In her article, UCLA political scientist Arely M. Zimmerman analyzes how the undocumented youth movement in the United States has transformed from being largely focused on passing the DREAM Act to increasingly using direct action to bring attention to broader issues of immigrant, civil, and human rights. As Zimmerman explains, the shift has been in response to a changing political climate, where the will to pass immigration reform has waned in Washington, deportations are on the rise, and local anti-immigrant ordinances are being considered at unprecedented levels.

While the DREAM Act has galvanized youth across the country, it has also recently come under increasing criticism, especially for the military provision in the present bill that, as a favor to Republican supporters, would allocate an additional $670 billion to the U.S. military.

“By supporting the DREAM Act, does this mean I automatically give a green light for U.S. forces to continue invading, killing and raping innocent people all over the world?” asks Arizona immigrant community organizer Raúl Alcaraz Ochoa. In an open letter to the DREAM movement, Ochoa details this and other reasons for withdrawing his support for the DREAM Act.

In Arizona, undocumented immigrants are not the only ones under attack—so are Ethnic and Mexican American Studies programs. But students in Tucson are responding. University of Arizona professors Nolan L. Cabrera and Roberto Dr. Cintli Rodriguez, and student Elisa L. Meza document the struggle to save Mexican American Studies in the Tucson Unified School District. Led by the radical youth organization UNIDOS and their direct-action tactics, community members staved off two school board meetings that threatened to effectively dismantle Mexican American Studies in the district. The authors point out the hypocritical discourse of Arizona leaders, such as former Arizona State superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Horne, who introduced the state ethnic studies ban while invoking Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Together all of these student movements are standing up for their right to free, universal education, without mandates from above over who gets to study or what should be studied. These movements are also increasingly collaborating across borders. On November 24, students from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Peru held a united day of Latin American student demonstrations.

“A continental movement is growing in defense of education as a right,” Jairo Rivera, spokesperson for Colombia’s National Student Broad Table, told BBC Mundo.6

This was the sentiment of both Giovanni Roberto and José Ancalao Gavilán, student leaders from Puerto Rico and Chile, who are interviewed by NACLA editor Michael Fox in the final piece in this Report.

“A new powerful generation is emerging and we cannot leave this responsibility to our children,” said Ancalao, spokesperson for the Chilean Mapuche Federation of Students. “We don’t know when this will end. . . . But what I can tell you is that we’re more alive than ever, and this movement is stronger than ever.”

1. Agência Brasil, “Em marcha em Brasília, professores pedem aplicação de 10% do PIB em educação,” October 26, 2011.

2. AFP, “Policía continúa desalojo de estudiantes que mantienen tomados colegios,” August 9, 2011.

3. Christopher Newfield, Unmaking the Public University: The Forty-Year Assault on the Middle Class (Harvard University Press, 2008).

4. Steven Roberts, “Ronald Reagan is Giving ‘Em Heck,” The New York Times, October 25, 1970.

5. George M. Dennison, “Privatization: An Unheralded Trend in Higher Education,” presented at the Governor’s Conference on Higher Education, Montana, October 2002.

6. BBC Mundo, “Los estudiantes de Colombia y Chile intentan exportar su protesta,” November 15, 2011.

Read the rest of NACLA’s November/December 2011 issue: “Latino Student Movements.”