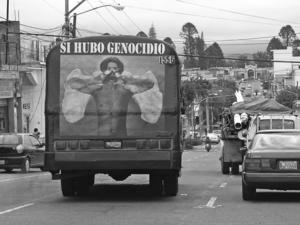

On May 10, 2013, before a packed courtroom, a Guatemalan court declared that it had found former de-facto president General José Efraín Ríos Montt guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity. The conviction was handed down for crimes committed against Guatemala’s Maya Ixil indigenous population during Ríos Montt’s 17-month rule in 1982 and 1983, the bloodiest period of Guatemala’s 36-year armed conflict.

The verdict came 30 years after the crimes and 13 years after survivors brought the complaint to the Public Ministry. The trial started on March 19, 2013 in an increasingly polarized environment. The three-judge panel of presiding judge Yassmín Barrios and her associates, Patricia Bustamante García and Pablo Xitumul de Paz, overcame several attempts by the defense to derail the process before the sentence was handed down.

The judgment is a testament to the resilience and courage of the victims who, after three decades of imposed silence, institutionalized impunity, and official denial, dared to speak out in a court of law about the brutal and systematic violence visited upon them during the scorched-earth campaigns orchestrated by the Guatemalan army. It is also a testament to the lawyers, prosecutors, and judges who worked to bring the case to fruition, often under a cloud of thinly veiled threats. That the verdict was vacated and a partial retrial ordered just 10 days later, on May 20, only confirms what the victims and their lawyers already knew: in Guatemala, justice is not won easily, and impunity is not easily defeated.

In the 718-page judgment, the judges determined that witness and expert testimony proved beyond a reasonable doubt that, under Ríos Montt’s command, the Guatemalan armed forces elaborated and implemented a series of plans designed to eliminate the Maya Ixil population as a group, since they considered that the Ixil as an entirety supported the guerrillas then waging war against the military government.

The judgment relied on witness and expert testimony, military documents, and other evidence presented over the course of 27 hearings, including a clip from the documentary film Granito in which a young Ríos Montt assures filmmaker Pamela Yates that as head of state he has full control over the army—“otherwise what am I doing here?” he says wryly. More than 90 Ixiles who were direct survivors of violence or relatives of victims testified before the court, as did experts from a variety of disciplines and specialties.

In the words of Judge Barrios, Ríos Montt had “full knowledge of what was happening and did nothing to stop it—having the knowledge of the events, and the power and the capacity to do so.” The court relied on military experts to find that Ríos Montt developed the national security plan and authorized military operational plans. Specifically, the court found that Ríos Montt ordered the development of Plan Victoria 82, knew of its contents, and authorized its enactment. As noted by National Security Archive analyst Kate Doyle, “Plan Victoria 82 sought first and foremost to destroy the guerrilla forces and their base through operations of annihilation and the scorched-earth tactics.” A collection of army records from July and August 1982 connected to Operation Sofia—a series of counterinsurgency sweeps through the Ixil region to kill enemy combatants and destroy their purported “base of support,” (i.e., the Maya Ixil population)—were given to the National Security Archive in 2009 and were used as evidence in the genocide case.

The court ruled that the prosecution and civil parties had proved the concrete crimes identified in the indictment—the murder of 1,771 Ixiles, the forcible displacement of 29,000, at least nine cases of sexual violence, and various cases of torture. The court described the nature of the violence deployed against the Maya Ixil as including indiscriminate massacres, rape and sexual violence against women, infanticide, the destruction of crops to induce starvation, the abduction of children, and the forcible displacement and relocation of surviving populations into militarized “model villages.” The court also described the forced participation of the population in self-defense patrols (PACs) as a method of destroying modes of self-governance and undermining local indigenous authorities, who were made to implement and enforce the obligation that men join the patrols.

Drawing on the evidence presented by the prosecution, the court was “totally convinced” that there was an intention on the part of the Guatemalan army to eliminate the Maya Ixil as an ethnic group and that the elements of the crime of genocide were met. The court found that the crimes were committed as part of a systematic plan to destroy the Maya Ixil as a group and were not spontaneous acts. The court also noted the killing by soldiers of fetuses—“the seed that has to be eliminated”—as support for the finding of sufficient intent to commit genocide.

The court also found that women were raped not only as the “spoils of war,” but as part of the systematic and intentional plan to destroy the Ixil population. Women reproduce life as well as culture, thus the exercise of violence on women’s bodies destroys the social fabric and helps ensure the group’s destruction. Judge Barrios made reference to the testimony of one woman who narrated her rape by more than 20 soldiers while she was held prisoner in a military base. The tribunal noted that many of the women still suffer pain and anguish as a result of the sexual violence they experienced.

The proceedings were under intense pressure from the very start. On the first day, Ríos Montt’s lawyer, Francisco García Gudiel, sought to have two of the three judges recused, and he was eventually thrown out of the courtroom. Later, after several weeks of intense witness and expert testimony—and just before concluding arguments were expected—a full-blown campaign was launched to sabotage the process midstream. A series of paid advertisements circulated in the press asserting that the genocide charges were fabricated, accusing the different actors involved in the trial of being guerrillas or their stooges, and preaching doom should Ríos Montt be convicted. One paid advertisement, featuring the signatures of respected politicians such as Eduardo Stein, asserted that the genocide trial represented an “end of the peace accords” and would open a new phase of violence in Guatemala. Others were more openly intimidating, including one entitled “The Faces of Infamy” that featured a wide range of actors from Attorney General Claudia Paz y Paz to the judges in the case, to human rights lawyers, international activists, and even U.S. Ambassador Arnold Chacon.

Once the judgment was emitted, a new campaign was launched to discredit the court and the verdict. In the days leading up to the Constitutional Court's ruling on May 20, defense lawyer Gudiel told the press that if the Court did not rule in favor his client, 45,000 of the general’s supporters were willing and ready to “paralyze” the country. The supporters were allegedly former members of the civil defense patrols (PACs). Government offices, including the Constitutional Court, received bomb threats. High-profile government officials, and especially Judge Yassmín Barrios, who presided over the trial, have become the targets of highly sophisticated media campaigns to discredit them. They have also been threatened with disciplinary sanction or even civil or criminal charges.

Guatemala’s powerful economic elites weighed in as well. The day after the verdict was read in open court, the Coordinating Committee of Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial, and Financial Associations (CACIF), the influential Guatemalan business association, asserted that grave violations had occurred and charged the trial court with being “overly ideological” and subjected to pressure and interference by unnamed international organizations. CACIF also called on the Constitutional Court to “rectify” the “anomalies produced in the proceedings.” They claimed that the genocide conviction tarnished all Guatemalans and urged citizens to challenge it to avoid being perceived internationally as on par with Nazi Germany. In a blog posted on CACIF’s website, author Philip Chicola expanded upon this argument. “Guatemala has joined the select club of genocidal states, together with Nazi Germany, the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda and Cambodia,” he wrote, and this would irrevocably tarnish Guatemala’s international image.

As is now well known, just 10 days after the historic ruling in the genocide case, Guatemala’s Constitutional Court vacated the verdict against Ríos Montt and ordered a partial retrial of the legal proceedings from April 19 forward. In theory, this means that all testimony and evidence produced from the trial start date of March 19 until April 19 remains valid, and only a few defense witnesses need to be heard before a new round of closing arguments commence and judges weigh the evidence and announce a new decision. In practice, however, the Constitutional Court decision is likely to require a new trial. The trial court judges who presided over the case had little option but to excuse themselves—which they did on May 27—since they had already announced an opinion in the case. On June 5, a new court was named to hear the case. But it is not yet clear whether it would be legal to hold a partial retrial, or whether a new trial will be required. If the latter happens, it would be a gross miscarriage of justice for the victims, since it would mean that the nearly 100 victims who testified—at great personal risk—would be called to testify again. And, given the determination of business elites and conservative politicians to impede justice for victims in Guatemala, will a new trial be allowed to move forward in any case? That justice can be done is not in doubt: this was demonstrated by the professional job done by the Barrios court, at great personal risk and under tremendous political pressure. The problem is that de-facto powers remain just strong enough that while they could not prevent justice from being done, they were able to undo it—and relatively swiftly—with virtually no consequence.

It remains an open question whether the victims in the genocide case will agree to participate in new proceedings given the perception that the verdict was vacated not on a legal technicality but as the result of undue interference by the Constitutional Court at the insistence of powerful sectors unwilling to back such a forceful challenge to their version of history. They may turn to the Inter-American system given their view that the verdict was annulled in an inappropriate manner, a view shared by two of the five judges of the Constitutional Court who wrote dissenting opinions to the May 20 ruling

Ríos Montt’s defense lawyers seem to have achieved—at least temporarily—their chief objective: by ordering a partial retrial, they have managed to create so many procedural difficulties that the way forward is murky at best. It remains to be seen whether the key actors within state and civil society can turn this around so that substantive justice can prevail in the case. At stake is not only justice for the Maya Ixil but for the thousands of other victims of human rights abuses who are seeking to hold those responsible accountable for their misdeeds. Whether this will be permitted in Guatemala remains an open question.

But, as stated in a Skype interview by Edda Gaviola, President of the Board of Directors of the Center for Human Rights Legal Action (CALDH), one of the civil parties in the genocide case, “Judicially it is unclear what is going to happen. But symbolically, and for the historical record, a judgment was made, and it was made by the trial court. It is now known that in Guatemala there was genocide.”

Jo-Marie Burt is Director of Latin American Studies at George Mason University. She led a delegation of Latin American judges and prosecutors to observe the Rios Montt trial, and was an international trial monitor with the Open Society Justice Initiative (www.riosmontt-trial.org).