This article is a joint-publication of NACLA and edmorales.net.

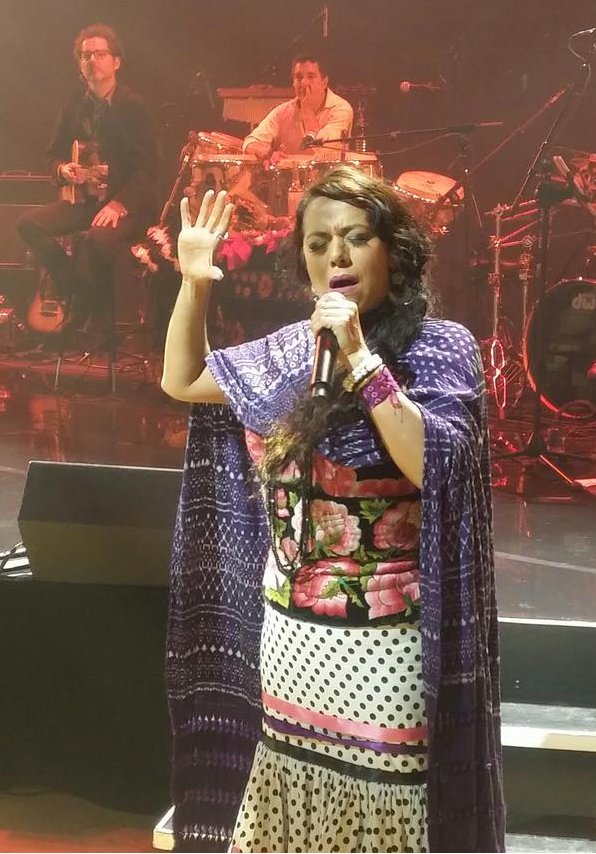

Lila Downs is a siren in the darkness, an ethereal range of many octaves seeking to blur borders and return wisdom to the earth. She appeared at The Appel Room at Rose Hall in Lincoln Center on Saturday, showering the audience with gifts from her life journey back and forth across the border between the United States and Mexico, one that is personal and political. “I grew up in Oaxaca…and Minnesota,” she said, noticing that the audience cheered more for the former. “Nobody’s clapping for Minnesota,” she laughed, perhaps in recognition of the stubborn intolerance that grows this side of the Rio Grande.

Nevertheless, she soldiered on, a guerrera de la luz, pushing back against the monocultural status quo with a Spanglish version of Cuban bolerista Osvaldo Farrés’s “Quizás, Quizás, Quizás“; a soaring, gentle take on “Cucurrucucú Paloma,” culled from her memories of Pedro Infante and Lola Beltrán; and a stunning performance of the ranchera “Paloma Negra,” her voice infused with a nomadic flamenco underbelly. Her guttural emotion made us jump in our seats like chocolate covered crickets, dissolving into gasping applause, calling for “otra,” from la voz del otro lado.

I got a chance to chat with Lila earlier in the week, and she gracefully held court on the process of recording “Raíz,” her latest Latin Grammy-nominated collaboration with Spanish singer Niña Pastori and Argentinean vocalist Soledad, as well as her life since she moved to Mexico, her thoughts on La Bestia, and what it means to live and make art on real and metaphorical borders.

Ed Morales: Are you enjoying being back in New York?

Lila Downs: It’s always good to come back north. We’ve been in Mexico for a long time now and we came up this week. So it’s exciting to get together with the New York cats, and a few of the Mexico City guys came in with us. We gave up our apartment here because my husband Paul got really sick, he has a heart condition and they told us that we didn’t have much time, and we thought, why don’t we move to Mexico for a while and take it a little easier? And fortunately two years have passed since that time—now I’ve learned that doctors scare you—and he’s been good.So we made the move then, but we’re planning on moving back to the United States—maybe not New York, but someplace else.

How did this last album with Argentinean singer Soledad and Spanish singer Niña Pastori come together?

We got approached by someone at the label. We signed at Sony two years ago, and they mentioned that Soledad, who is this artist from Argentina, was very interested in collaborating with me. I had heard about Soledad, and actually invited her to sing with me at a concert one time in Argentina. And then they also mentioned that they had the idea of inviting another singer from Spain. We weren’t sure at that point who, but then when they mentioned Niña Pastori, I got very excited and thought, wow this sounds like an exciting project and something to learn from, combining these influences of music.

So we met and that was the easy part, but of course the collaboration in the studio was a little more complicated vocally speaking because we’re each in very different ranges. Soledad and myself are similar. Niña is an octave away from each of us, so we figured that out later on and had to adapt to the different keys. It worked out very well, and in the middle of the recording we were invited by Carlos Santana to record on his album Corazón and did a song with him too.

How did the collaboration go?

Soledad comes from a province that’s very strong and very culturally specific in southern Argentina, called Santa Fé. And the thing that’s similar between those two is that they began singing traditional folk music when they were very young, like kids, around eight years old, and they became sensations when they were quite young, and in that way they were very similar to each other. And even though I started singing when I was young, I didn’t have the fame that they had, so we were a bit different in the way that we approached things. At first it was quite different and maybe a little bit difficult, the communication between the three of us, but then we got to know each other better and learned to respect each other a little bit more than before.

Did you feel like you were kind of re-writing the Latin American musical canon from a women’s point of view?

The three of us have that experience as people. The songs show that. For me composing songs has a lot to do with my political and social circumstances. Being Indian in Latin America is kind of marginal, so the songs that I have written have a lot to do with that story. It’s an important element in the songs that I’ve written. There’s a song that I was starting to perform, also that Soledad sings, called the “Train to the Sky,” or “El Tren del Cielo.” And this song, right away when I heard it I thought of this train that we call the Beast that runs right through Mexico, and brings all the Latin American immigrants, and so when I perform it I dedicate it to them, and it’s a very positive take on it. I think originally the song was written in the Andes, where there’s a train that goes very high up in the mountains in that area of Argentina.

How did you come to know about La Bestia?

I started writing some verses about it because I have been so appalled by the news that we get in Mexico, and a lot of the times there is police involvement in these stories, corrupt police. So it’s very frustrating and I’ve been thinking about this issue for quite a while. I am now writing a song for our next album that is about chocolate and cacao, and it’s a song that goes to these different countries like El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Venezuela, Guatemala, and Mexico. The route of cacao starts in these different countries, and it’s fascinating that it coincides with something that we all consume with a kind of greed, while at the same time it’s the place of origin of all these children that are coming to the United States. So I’m writing some verses about this and there are these contrasts of the sweetness of chocolate and the bitter world that we live in for these people.

Why did you decide to re-record “Zapata se queda"?

I actually didn’t choose that, Soledad chose it to reinterpret in her manner, and she did it in a traditional saya, which is this kind of warrior hymn. It’s very beautiful, it’s kind of scary—something scary about it. But this song I originally wrote when I had been having—well I was waking up at three in the morning. And in Indian native thought, in Indian consciousness, we believe in ghosts, and we believe that around this time is the most active time for them to visit. And I mentioned this to a healer that I visit in Oaxaca, and she told me to place a glass of water and a red flower and these different symbolic elements that were supposed to help me. And in the meantime I was suffering with this waking up at three in the morning every night and I would feel this very dark energy in my room. I mentioned it to my mother and my mother said, “Why don’t you pray and kind of think of who you think it may be?” And these were times—this was four years ago when we started seeing all these dramatic things on the news in Mexico, you know these decapitated people on the news and pieces of bodies, and in the midst of this I felt like saying to Zapata, “Come on, give us some direction here!” Maybe it was him who was coming to visit me. And this song had been kind of hanging around for a while, so I wrote these verses to him.

The version of “La Maza” was quite strong, tell me about it.

Niña chose it, and the classic is the Mercedes Sosa version, and it’s quite a different take on the song and it has been very beautiful to see the reception of it, kind of like going back to the old world once again with the gypsy interpretation of it. They invited a mariachi band to play on that song, which makes it even more interesting musically, so it was exciting to hear it in a different context.

What kind of things did you three share, common threads?

I think it’s a beautiful opportunity for the different Latin countries to be represented in the folk tradition, but the kind of folk that we do is fused with modern elements. Every time that we come together it’s always a learning experience with Niña culturally and as a musician. And Soledad as well, I think we all learn from each other, we all have very different personalities, so it’s fun.

What are the plans for your next album with them?

I’ve been talking about doing some jazz standards and doing my own compositions with more jazz musicians, maybe inviting some people like Wynton Marsalis, and Eddie Palmieri, and Brad Mehldau. We’ve been wanting to do this for a long time but haven’t had the chance or the time to devote our energy to it, so I think it’s kind of the next step. We’re doing two albums. It would be that one and also an album of mostly original music with a few duets, maybe Juan Gabriel and one cut hopefully, hoping for him to accept, and maybe Juanes on another. Just very grateful for life, and I told you about Paul’s story, and I think it’s just enjoying life and trying to enjoy the place that we’re in, and I’m very grateful.

Do you think awareness of what you try to do with your art has increased or have we taken a step back as a culture?

I think in the United States we have a lot of work to do still, and I think that people are very ignorant of who Latin Americans are, so I feel a responsibility to continue our work. I have been a little bit—because of personal reasons we moved to Mexico, so, that was good because our audiences definitely grew a lot there. Mainly we’re doing concerts for about 10,000 people every time, which is very exciting to see. When I started, I always felt like I was swimming upstream. So it’s rewarding to feel that somehow you are contributing a grain of sand to this immense body of knowledge that people should have about who we are and how beautiful tradition and folk can be.

At the same time, musically, hopefully this is what changes people and makes them reflect on life, on the bigger things. And here in the United States I think we still have a lot of work to do, but I do feel like there are a lot of positive things happening. Culturally we are a very strong influence and that is undeniable, but also there is a certain collective conscious denial of who we are—including in ourselves, in our own communities. I think in the end once you learn how the subconscious—I don’t know how it works but I know that in the end it’s there and it may be not palpable, it’s not tangible, but at one point it will seep out, and it already is, culturally and in many other ways. So I’m an optimist and I look forward to a time when things will be more positive.

Has living in Mexico increased your closeness to the culture?

You never stop learning from anything and being able to go back and forth is such a privilege and a gift because you’re able to become more effective about things and also become more sentimental about them, and it’s very enriching for the art, definitely.

Do you feel strongly about being a bicultural “border” person?

It’s become part of my condition to be a border person, and I think that, for example, we just did a month tour in California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas and it was just the most beautiful experience, going through these states that originally were Mexico and have kind of another vision of what being Mexican American is. Completely bilingual, all these states are, so you know, that’s cool, and it feeds the music and it feeds the soul to be in these places that are always transforming and changing. It’s kind of like being in New York City in a way, it’s different extremes.

Do you think we’re moving toward a future of eliminating borders in the way we look at people?

I think that being perceived as an immigrant is kind of a backwards situation that still happens to us but I think in the future it’s going to be much more progressive in that way, and it already is in cultural ways that are unspoken. But people enjoy living those differences that make us more appreciative of humankind.

Ed Morales is a freelance journalist and author of Living in Spanglish (St. Martin’s Press). He teaches at Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race, and is a NACLA contributing editor.