This article is a joint publication of NACLA and Foreign Policy in Focus.

“Alive they were taken, and alive we want them back!”

That’s become the rallying cry for the 43 student teachers abducted by municipal police and handed over to the Guerreros Unidos drug gang last September in Iguala, Mexico. None have been seen since.

It remained the rallying cry even after federal officials announced that the missing students had most likely been executed and burnt to ashes.

Since then, Argentine forensic experts have concluded that burned remains found in Iguala do not belong to the missing young men—and so the 43 remain undead. The findings speak to a growing skepticism about the Mexican government’s competence—not only to deliver justice, but also to carry on an investigation with any kind of legitimacy or credibility.

It has become ever clearer that the state is in fact deeply implicated in the violence it claims to oppose. The student teachers were originally attacked by municipal police—allegedly at the orders of Iguala’s mayor and his wife, who were at a function with a local general when the attack took place. Although the exact details of who ordered the attack are not yet clear, the handing over of the student teachers to a violent drug gang betrays a thorough merger of the police force, local officials, and organized crime.

This growing realization has ignited rage all over Mexico, with social media campaigns flaring up alongside massive street protests. Peaceful marches happen almost daily in Mexico City, while elsewhere there are starker signs of unrest. Some demonstrators even set fire to government buildings in the Guerrero state capital.

Meanwhile, the government has carried on an increasingly clumsy investigation, first purporting to have found the students in nearby mass graves—as The Nation reports, plenty of mass graves have turned up, but none has yet been proven to contain the missing teachers—and then claiming to have extracted confessions from the alleged killers.

In a November press conference, Attorney General Jesús Murillo Karam showcased detailed video testimonies from three alleged hit men who claimed to have burned the 43 at a nearby garbage dump. Parents of the missing went to inspect the alleged site and found evidence lacking. Many doubted that a fire of such magnitude—the supposed killers claimed that they had spent 14 hours burning the bodies—could have happened due to the rain of that night.

When Argentine forensic specialists disproved Karam’s narrative, the federal government pledged to “redouble efforts” to find the students. Now President Enrique Peña Nieto is hinting at a conspiracy against his government. It’s hard to escape the conclusion that Mexican officials want this issue put to rest as soon as possible.

Meanwhile, the mounting number of mass graves investigators are turning up serves as a reminder that this kind of violence has been going on for years. Police round up, detain, beat, arrest, and shoot at student activists routinely, as when state police shot and killed two Ayotzinapa students during a protest action on the highway in 2011. As with over 90 percent of such crimes in Mexico, no one has been punished. These kinds of killings and disappearances have a long and sordid history as a practice of state violence in Mexico—and particularly in Guerrero—since the so-called Dirty War of the 1970s.

The many discrepancies in Karam’s press conference are feeding into a growing popular refusal to trust the government’s ability to investigate the disappearances independently.

In response to a reporter’s question about whether the parents of the missing believed him, Karam quipped that the parents are people who “make decisions together.” The question was not so much about whether the parents, as individuals, believed or disbelieved Karam’s evidence—although they have since visited the alleged crime scene and reaffirmed their skepticism.

Instead, ordinary Mexicans are increasingly employing their collective intelligence in making sense of the events and refusing to accept the state’s evidence on the grounds that the state itself is compromised. And just as importantly, they’re condemning the government’s silence about its own complicity in the probable execution of their sons.

In their increasing rejection of the Mexican narco-state’s legitimacy, the parents of the missing 43 are signaling their membership in what anthropologist Guillermo Bonfíl Batalla famously termed México Profundo—that is, the grassroots culture of indigenous Mesoamerican communities and the urban poor, which stands in stark contrast to the “Imaginary Mexico” of the elites. Recalling the Zapatista movement, the rumblings from below in the wake of the mass abduction in Guerrero are merging with older modes of indigenous resistance to give new life to Mexico’s deep tradition of popular struggle.

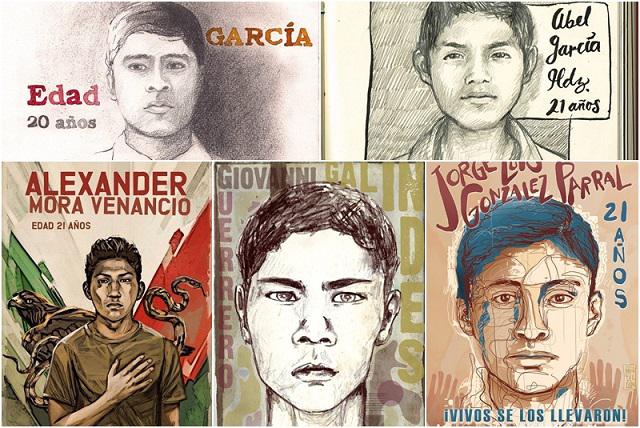

Bolstered by social media, this new life is expressing itself in a number of colorful ways. Defying the government’s theater of death, artists from all over the world are creating a “Mosaic of Life” by illustrating the faces and names of the disappeared. Mexican Twitter users have embraced the hashtag #YaMeCansé—“I am tired”—to appropriate Karam’s complaint of exhaustion after an hour of responding to questions as an expression of their own rage and resilience.

Gradually, a movement calling itself “43 x 43”—representing the exponential impact of the 43 disappeared—is rising up to greet the undead, along with the more than 100,000 others killed or disappeared since the start of this drug war in 2006 under former President Felipe Calderón. This refusal of the dead to remain dead made for a particularly poignant Dia de Muertos celebration earlier this month.

This form of resistance recalls what happened last May in the autonomous Zapatista municipality of el Caracol de la Realidad in the state of Chiapas, where a teacher known as Galeano was murdered by paramilitary forces. At the pre-dawn ceremony held there in Galeano’s honor on May 25, putative Zapatista leader Subcomandante Marcos announced that he, Marcos, would cease to exist. After Marcos disappeared into the night, the assembled then heard a disembodied voice address them: “Good dawn, compañeras and compañeros. My name is Galeano, Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano. Does anybody else respond to this name?”

In response, hundreds of voices affirmed, “Yes, we are all Galeano!” And so Galeano came back to life collectively, in all of those assembled.

And now 43 disappeared student teachers have multiplied into thousands demanding justice from the state and greater autonomy for local communities, which are already building alternative healthcare, education, justice, and governmental systems. A general strike is scheduled for the anniversary of the Mexican Revolution on November 20th.

In Mexico’s unraveling, there is an opportunity for the rest of the world to witness—and support—the emergence of more direct and collective forms of democracy. As the now “deceased” Marcos said: “They wanted to bury us, but they didn’t know we were seeds.”

Charlotte María Sáenz is a contributor to Foreign Policy In Focus. She teaches Global Studies at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco. A longer version of this piece originally appeared at Other Worlds.