As most now know, Bolivian President Evo Morales suffered a narrow defeat in the constitutional referendum vote on February 21. A 'Yes' vote would have allowed Evo to represent his Movement to Socialism Party (MAS) in a run for a third term in 2019. Despite recent setbacks, it seemed that the combination of economic success and political support within Bolivia would lead Evo to a win, and a chance to serve nearly two decades in office. Yet by the middle of February, Evo was in the midst of an increasingly messy situation. There were growing revelations about an ex-lover, a love child, and corruption tied to a Chinese firm. Was Evo, who always seemed above the scandals that plagued the administration, caught in a tragic drama of lust and influence-trafficking?

Evo denied it. The child had died in infancy, he claimed he was told. And, despite evidence to the contrary, he said he had no more ties with the child’s mother. Yet the opposition rediscovered its internal feminist and decried Evo’s machista lack of rectitude. How, they asked, could he be so dismissive of the whole affair? Meanwhile, Evo was already dealing with fallout from a corruption scandal at FONDIOC, the Indigenous Development Fund. As officials closer to Evo began falling under the investigative lens, a long muffled racism erupted. Here was the chance to destroy Evo, supposedly the world’s iconic representative of Indigenous and popular struggle. The moment was ripe for detractors of all political stripes to attack.

It was no coincidence that four days before the vote itself, a parents’ protest against the opposition mayor of El Alto, La Paz’s sister city, turned tragic. Groups of young men – some say part of the march, others say hired agitators – incited marchers and set fire to the municipal building. In the blaze that ensued, six city employees died from smoke inhalation. What was already a tense campaign exploded. Both sides accused the other of the blaze, labeled a “massacre” on par with the army killings of 87 people in 2003. Accusations of corruption, criminality, and murder flew back and forth, most reproduced through a largely anti-Evo social media sphere. Similar to the response after the 2003 Gas War, when former President Goni was labeled a murderer, graffiti in El Alto now read ‘Evo asesino’ (Evo, assassin). The tactic, straight out of a handbook for sabotage and destabilization, clearly played against Evo.

It is doubtful that the MAS would have made such a serious miscalculation by instigating violence days before the vote. Yet truth be damned. The media and the “redes sociales” (Twitter, Facebook, and the like) deemed Evo guilty. We may never know how this impacted the national vote, but by the evening of February 21st, the ‘No’ had eked out 51.27%. Yet far from merely resolving the question of re-election, the fraught situation has erupted into full-blown political drama.

Who voted ‘No’? Opposition parties of the right and center-right, splintered among themselves, but unified against Evo, were at the fore. Here was the old guard of the neoliberal era angling for a political future: perennial candidate and cement magnate Samuel Doria Medina and former President Tuto Quiroga, a protégé of ex-dictator (and ex-president) Hugo Bánzer. And, out of the ashes of the 2003 Gas War came Carlos Sánchez Berzaín, the former MNR (Revolutionary Nationalist Movement) Minister of Defense of ousted President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada. From the U.S., Sánchez Berzaín launched a stream of virtual attacks using the Venezuelan right’s strategy of labeling Evo a 'dictator.' (Both Sánchez Berzaín, in Miami, and Sánchez de Lozada, in Maryland, are facing a civil suit in U.S. courts for crimes against humanity.)

Newer regional parties also joined the ‘No.’ These included the Demócratas, led by Rubén Costas, the governor and one-time agitator for a racist autonomy project in Santa Cruz, and the new Sol.bo party. Sol.bo is a hodge-podge of right-leaning pols and former MAS militants whose party recently captured the governorship of La Paz, and the mayor’s office. Right-leaning intellectuals who call themselves liberal in the Latin American sense joined this crowd and created their own platform for the ‘No.’

All of this was to be expected. But, for some progressives, there appeared to be ambivalence as well. As Emily Achtenberg recently wrote for NACLA, there were plenty of reasons to vote ‘Yes.’ Along with a booming economy and an array of efforts to help the poor, were not Evo and the MAS the bulwark against American imperialism and the revanchist tendencies of the right? Perhaps. Yet as more than one colleague said, “the people are exhausted.” Desgaste, exhaustion, was the word I heard most frequently: Evo’s party suffered from political exhaustion (desgaste político). Too many deals with too many interests had created machination, manipulation, and corruption within the government. The exodus of committed pro-MAS militants meant that the party’s vision of democratic and cultural revolution had been penetrated by the “neoMASistas” or the “new MAS-istas”– that is, politically interested actors of various stripes with little ideological conviction.

The process was slowly unraveling to the point that one once sympathetic observer wrote that Evo had become his own worst enemy. The legacies of the 2011 TIPNIS conflict and corruption at the Indigenous Fund were but the tip of the iceberg. The MAS had overseen the weakening of its commitment to its own constitution. The symptoms of this unraveling were visible in the opposition of a range of critical intellectuals on the left who had also expressed their discontent.

Key intellectuals, like Raúl Prada, exited the pro-MAS fold soon after the constitutional assembly went astray, and have waged a steady critique of the political and ethical dismantling of the MAS’s proceso de cambio (process of change). Defenders of Indigenous rights, like Alejandro Almaráz, had also decamped as government land reform efforts weakened. Another group of critical intellectuals, many with sympathies on the left, formed a coalition called ‘No Means New Opportunity.’ These critics, most part of the left-leaning middle-class, argued that a ‘Yes’ vote would further erode democratic institutions constructed out of years of struggle.

Still other prominent intellectuals, from Silvia Rivera Cusicanquí to María Galindo, have for some years been responding with acerbic disdain to the MAS’s embrace of male-centric, backroom politics fueled by deal-making, misogynism, homophobia, and prepotencia. The latest scandal, tied to Evo’s apparently nonchalant dismissal of his former lover, child, and affair gone awry, is but one of many such moments. Another ‘No’ emerged from Indianist intellectuals of the Andes, most of them Aymara, who have critiqued Evo for some time. Evo, they argue, has been captured by ‘white and mestizo’ interests of the old ruling class, betraying the Indigenous rebellion that led to his rise. And they criticize the folklorization of the Indigenous struggle – its conversion into the celebration of seemingly clownish rituals, the costuming of Evo and Vice President Álvaro García Linera for every staged event, and the increasingly empty invocation of Pachamama, the Mother Earth.

And among social movements of all kinds, factions have lined up on either side of the ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ divide. To be sure, both the MAS and the right-wing parties have contributed to these divisions. Political parties in Bolivia have always worked to absorb autonomous movement struggles into the divisive logic of party politics. All of this made for an uncomfortable encounter between the progressive ‘No’ and the ‘No’ of the racist, reactionary, and revanchist right. Vice President Alvaro García Linera came out as the votes were still being counted to denounce the destabilizing efforts of the right and to remind his ‘progressive’ detractors that there was “no such thing as a ‘No popular.’” A vote against Evo, he intimated, was a vote for the empire.

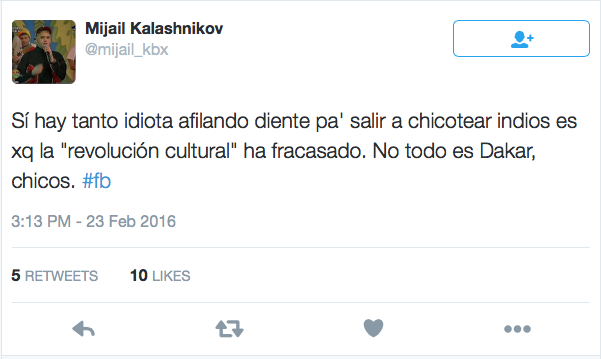

Even so, Evo and the MAS maintained significant support in the cities and in the rural countryside. Despite the violence in El Alto, the ‘Yes’ vote won there with 58%. In the eastern bastion of anti-Evo sentiment, Santa Cruz, the ‘No’ only took 60% (but took 65% in the city itself) – even 40% support is remarkable in this conservative region that once demanded ‘autonomy.’ Nonetheless, one might have expected a bit more gratitude from Santa Cruz. Evo and Álvaro had retreated on land reform, gone out of their way to extend credit and support to the agroindustrial elite, and deepened support for the oil and gas industry, whose headquarters are centered in the east. The MAS had neutralized its revolutionary platform to appease these elites. Construction and banking were booming. To add insult to injury against the Pachamama, for the past two years the government has sponsored the Dakar Rally, a noxious fossil-fueled spectacle that carved across pristine Andean landscapes. Dakar was one of many ways the MAS reached out to the cultural and political carnival that describes the politics of the Bolivian East. Morales and García Linera even posed and squinted alongside beauty queens, motorbikes, and dune buggies, applauding a spectacle closer to Mad Max than Buen Vivir. Yet as the victory of the ‘No’ became clear and racist vitriol against the MAS erupted, the façade of hegemony eroded. One sardonic observer watching the racism explode on Twitter quipped, “If all these idiots are sharpening their teeth to go out and beat up indios, I guess it’s because the cultural revolution has failed. Not everything is Dakar guys.”

Political exhaustion is undeniable. But one should be careful in their reading of the 'Yes' and 'No' votes. On the Twittersphere and in the media, both distorted and unrepresentative, there seems to be deep and vicious polarization. Yet many on the ‘Yes’ side likely voted as much for job stability as for deep conviction. And many on the ‘No’ side, especially the progressive left, voted for renewal based on ideological commitment. Yet it may not be the referendum vote that really matters now. In the wake of the violence, and both before and after the vote, there appear to be orchestrated efforts underway to destabilize the regime. The actions of the MAS in coming months may or may not help. During the voting itself, it was clear that the right – a la Venezuela – planned to declare fraud whether it existed or not. Indeed, as results flowed in, anonymous operators on Twitter posted images of voting results and webpages – duly adulterated – suggesting that the electoral body was engaged in fraud. In turn, unexpectedly complicit tweeters from World Bank economists to university intellectuals, duly passed on these posts, contributing to a crowd-sourced fraud of their own. Agitators and some otherwise respected journalists called for “vigils” outside of the electoral tribunal’s office, a clear effort to generate public unease and distrust. None of these fraud claims, to the best of my knowledge have been substantiated. But the intent was clear, as was its effect: to amplify a sense of polarization, confrontation, and abject disgust.

Assuming the right-wing fails in the attempt to lay the groundwork for an early resignation, Evo’s term will come to an end on January 22, 2020. What will come next? On social networks, the focus is now on the Chinese firm, the ex-lover, and the love child. Some say the child lives, for others the child itself is a phantom. The increasingly sordid affair is entangling Evo’s circle into ever-deeper webs of Machiavellian urges and intrigues. In the longer term, a new intellectual struggle is emerging. There is a link between convergent interests from D.C., through Miami, and Caracas to La Paz: to destroy the “image” of Evo and the leftist and Indigenist struggle that he represents around the world. Talk of desgaste may reflect reality, but it is also tactical. It fuels the abandonment of illusion of progressive hope tied to the entire decade of change.

With a hint of smug self-righteousness, the technocrats of the1990s are already writing about entrepreneurialism and the new post-Evo economy of Bolivia. They are already chipping away at the successes of the MAS government, discrediting it as an anomaly, saying poverty reduction was only due to the high price of gas, saying credit is due not to Evo but to the neoliberal reforms of former President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada. In a not-so-subtle way, racism masked in the language of culture may return to the fore. Will we hear again that indios are not fit for governing (never mind five centuries of colonialism)? Was the Pachamama all just indigenous farce? Stay tuned.

Yet it bears remembering that the ‘Yes’ vote represented nearly half the country, scattered far and wide, in cities and towns, Indigenous and otherwise. “The ‘Yes’ will win,” Indigenous movement activists told me in days prior to the vote. “It has to win.” Here the concern was that the end of Evo might bring the return of the past. What would happen to the fragile gains carved out from marches, blockades, and violence suffered at the hands of landlords and right-wing thugs? Have we fought for this only to give it away, people asked? For those on the edges, Evo had come to mean hope and possibility.

Evo remains a historical marker in the collective struggle of a thousand battles over many decades, if not centuries. Of course, there were divisions in the movements, when had there not been? Of course there was corruption, but have we not seen that for many decades with the criollo elites? The ‘Yes’ movement was not a marker of blind approval. It came whether or not Evo represented desgaste and immorality to the urban NGOs. A ‘Yes’ for Evo was a yes for the longer history of struggle and hope for its future. As the gas bonanza enters difficult days, we can hope that the progressive ‘No’ of the NGOs and the bookish classes can return to the popular ‘Yes’ of the movements. For it is there, not in the redes sociales or the prognostications of the technocratic class, that hope for Bolivia’s future resides.

Bret Gustafson teaches Social Anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis. He is the author of New Languages of the State (Duke University Press, 2009) and co-editor, with Nicole Fabricant, of Remapping Bolivia: Resources, Territory and Indigeneity in a Plurinational State (School for Advanced Research Press, 2011).