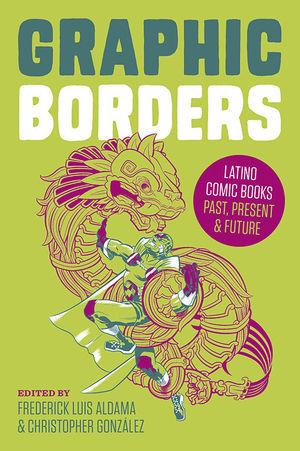

There are no limits to the ways in which Latin@s can be represented and imagined in the world of comics. However, until now this area has been relatively understudied. The recent book Graphic Borders: Latino Comic Books Past, Present, and Future (University of Texas Press, 2016) presents the most thorough exploration of comics by and about Latin@s currently available. This exciting graphic genre conveys the distinctive and wide-ranging experiences of Latin@s in the United States, from Latin@ superheroes in mainstream comics to subcultures on the indie spectrum like Love & Rockets.

We asked the co-editors of Graphic Borders, Frederick Luis Aldama and Christopher González, a few questions about their new book.

What drew you both to pursue this project?

While scholarship on comics has come into its own of late, it’s largely been focused on white (usually male) creators and creations—and this in all the different styles, from the superhero to those of the Underground and Alternative scenes. Of course, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with this. And, we completely understand the scholarly compulsion; this has been the reading diet of most scholars working on comics in this country. And, we understand the significance of this work: to move forcefully comic book studies into centers of Ivory Tower knowledge making.

However, there’s much more to this story. There’s much more that needs our scholarly excavation and attention. Comic books by and about Latinos is a vital living, breathing archive of extraordinary creativity in need of our careful scholarly attention. It demands this.

Today, we as Latinos in the U.S. are the majority minority. We’re seeing more and more Latinos pushing through the gates—and this in spite of the persistence of a push-out/lock-out education system. With pencil and paper and access to comics and any other cultural art forms, Latino comic book creators have been using this format to tell our stories and histories—and also to take us to places as yet unimagined. With access to the Internet with its funding and distribution platforms, these creators have been creating comics that reach readers across the country—the planet.

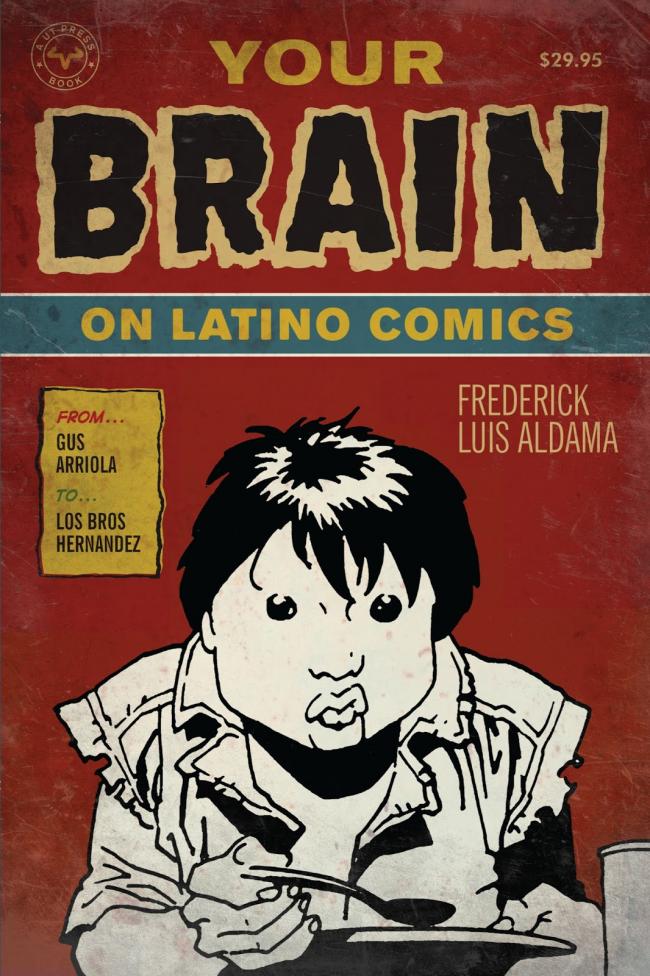

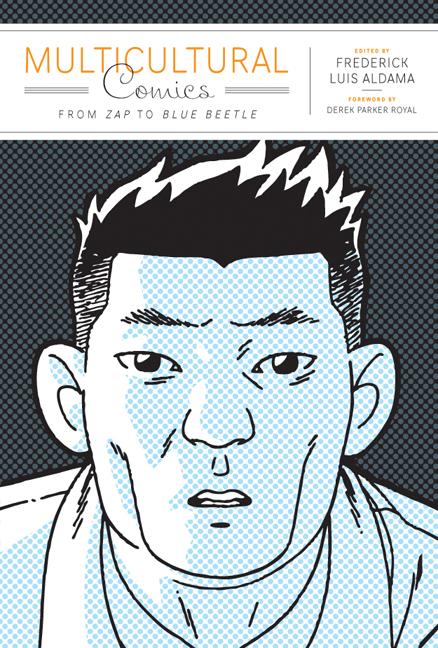

Of course, we love these Latino comics so it doesn’t take any arm-twisting to get us to put to together a volume like this; or, in the case of Aldama, to write the first book on Latino comics (Your Brain on Latino Comics) and edit one of the first volumes on multicultural comics (Multicultural Comics: From Zap to Blue Beetle); it’s why Aldama’s about to publish Latino Comic Book Storytelling: An Odyssey by Interview—a project González contributes too as well. It’s why González edited a special issue of ImageText on Los Bros Hernandez and is finishing up his book on Gilbert Hernandez.

Of course, we love these Latino comics so it doesn’t take any arm-twisting to get us to put to together a volume like this; or, in the case of Aldama, to write the first book on Latino comics (Your Brain on Latino Comics) and edit one of the first volumes on multicultural comics (Multicultural Comics: From Zap to Blue Beetle); it’s why Aldama’s about to publish Latino Comic Book Storytelling: An Odyssey by Interview—a project González contributes too as well. It’s why González edited a special issue of ImageText on Los Bros Hernandez and is finishing up his book on Gilbert Hernandez.

For us, to bring together these extraordinary scholars to enrich our understanding of comics by key shapers in our planetary republic of comics is a no brainer. It’s this sense of inclusivity and attention to the verbal-visual storytelling margins that led us to undertake the herculean work to edit the 350,000 double volume, Encyclopedia of World Comics.

For us, to bring together these extraordinary scholars to enrich our understanding of comics by key shapers in our planetary republic of comics is a no brainer. It’s this sense of inclusivity and attention to the verbal-visual storytelling margins that led us to undertake the herculean work to edit the 350,000 double volume, Encyclopedia of World Comics.

At one point, it was Shakespeare’s moment and at another, Gabriel García Márquez. Today, it’s our moment. It’s the moment of extraordinary creation of comics by and about Latinos—and we’re here along with our scholarly hermanos and hermanas to shout this from rooftops.

What makes Latina/o-created comics unique?

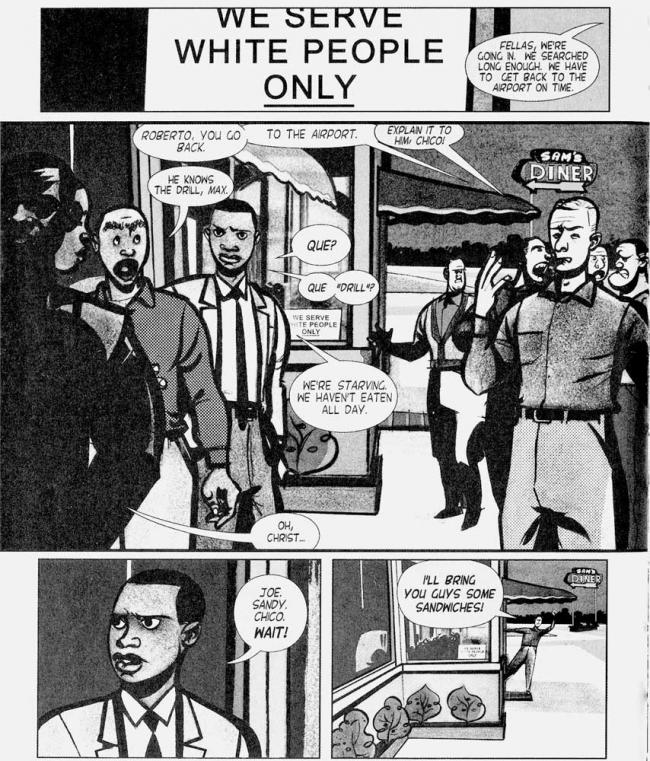

There are two levels of comics creation to keep in mind here: the content and the form. Not surprisingly, some (most) Latino comic book creators have chosen to recreate experiences, stories, histories that have otherwise been swept to the side in mainstream culture. But the shape given to this content—this very varied Latino-ness, if you will—is extraordinarily diverse. Someone like Lalo Alcaraz (the subject of Juan Poblete’s work in this volume) chooses to reproduce our experience, giving it the form of satirical political cartoon; others like Los Bros Hernandez choose to recreate our experience by fleshing out huge storyworlds overflowing with an abundance of characters from all walks of life—and each (Gilbert and Jaime) with their own unique aesthetic style. Those like Wilfred Santiago (the subject of González’s scholarship herein) gravitate toward biography: Robeto Clemente’s breaking of color and linguistic barriers as one of the first Afro-Latino players to make it in baseball’s major leagues. Yet others like Javier Hernandez (El Muerto) and Rafa Navarro (Sonambulo) breathe new life into Marvel/DC narrative conventions with their creation of ancestrally rooted Latino superheroes.

To put it simply, there are no limits to the imagination when it comes to Latino comic book creators and their choices in terms of content and form. What we see today is that most (and to varying degrees) tend to choose to fill out their content with ingredients that speak to the Latino identity and experience. What we see today is that most take from and make their own (and make new) all those shaping devices and styles that make up our planetary republic of comics.

How do some of the works examined in your book speak to Latina/o and Chicana/o audiences?

Whether it’s an analysis of Gilbert Hernandez’s stand-alone graphic novels, Alcaraz’s La Cucaracha, Wilfred Santiago’s 21: The Story of Roberto Clemente or Marvel’s Latina Spider-Girl or Blatino Spider-Man, DC’s Latino Blue Beetle or gay Latino Bunker, each shows the world of comics and its readers that we too can be agents transformation; in the many comics by and about Latinos that are explored in this volume we not only experience complex characters, but we see ourselves in their pages. We are also made aware of not only the skill and expertise of the creators, but the new generations of Latino scholars see that this can be an area for serious, committed scholarship.

How have some Latino creators sought to correct misrepresentations of Latino history?

The very fact of having a Latino creator on the cover of a comic is a correction to comic book history. Of course, Latino creators infuse their comics with greater or less degrees of Latinoness, from characterization to recovery of our histories and mythologies. No matter how visible this Latino content is, the very fact that Latinos are creating visual-verbal storyworlds is a sea change. The floodgates have opened!

What challenges did first-wave Latino creators in the 1980s encounter when trying to get their work published?

Los Bros Hernandez were the first out of the gate with Love & Rockets. It’s this comic’s success that singlehandedly grew Fantagraphics Press into the alternative comics publisher it is today. That said, not all experienced such good fortune. Many other Latinos that were coming up in the 80s and especially the 90s knocked heads against publisher and distribution. Those like Javier Hernandez, Rafael Navarro, Richard Dominguez, and Laura Molina (some studied inGraphic Borders) had an especially difficult time; while they continue to create and distribute their work, it’s largely through grass-roots means. They all have day jobs to support their art.

While Latino comic book creators are relatively legion today as compared to yesterday, they still face all sorts of closed doors when it comes to the big publishers and distributors. Some have tried to work with the big guns, but found that they were being asked to compromise too much their creativity, so they cut.

It continues to be a struggle—and especially so for Latina creators. To help tip scales, Aldama just launched his Latinographix series that publishes actual comics created by Latinos. As they say in our community, sí se puede!

Where would you recommend a reader start with Latino comics?

Take the weekend off and dive into, well, all of them!

Here are some of our fav. creators: Lalo Alcaraz, José Cabrera, Hector Cantú (with Carlos Castellanos), Jaime Crespo, Richard Dominguez, Frank Espinosa, Eric J. Garcia, Marisa Garcia, Crystal González, Jason “JGonzo” González, John González, Raúl Gonzalez the Third,Gilbert Hernandez, Mario Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez, Javier Hernandez, Andrew Huerta,Alberto Ledesma, Liz Mayorga, Laura Molina, Rhode Montijo, Rafael Navarro, Alex Olivas,Daniel Parada, Jimmy Portillo, Jules Rivera, Cristy C. Road, Fernando Rodriguez, Grasiela Rodriguez, Hector Rodriguez, Jason Rodriguez, Octavio Rodriguez, Rafael Rosado, Carlos Saldaña, Wilfred Santiago, Serenity Sersecion, and Lila Quintero Weaver.

This article originally appeared in the University of Texas Press blog.

Frederick Luis Aldama is Arts and Humanities Distinguished Professor of English and University Distinguished Scholar at the Ohio State University.

Christopher González is an assistant professor of English at Texas A&M University-Commerce.