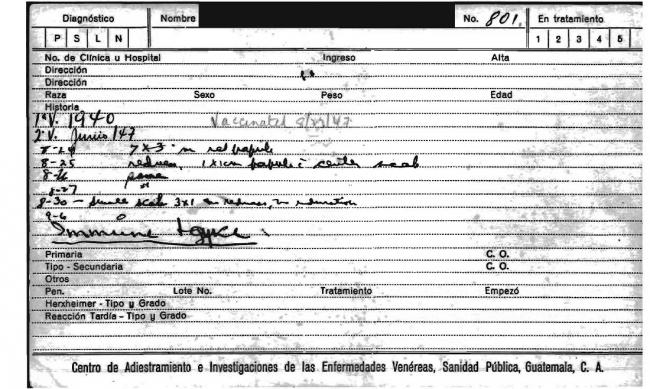

Federico Ramos Meza was just 20 years old when he claims to have been infected with syphilis during experiments led by the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) in the late 1940s. Ramos wasn’t alone. Between 1946 and 1948, USPHS and Guatemalan medical doctors exposed 1,308 Guatemalan prisoners, psychiatric patients, soldiers, and sex workers to diseases like syphilis, gonorrhea, and chancroid. Records show that the U.S. scientists involved in those experiments did not treat the majority of Guatemalans nor did they receive informed consent from their subjects.

A former soldier for the Guatemalan military, Ramos is today 90 years old and resides with his family in a mountain village two hours by truck from the nearest health clinic. He and his family members complain of health problems they believe resulted from the syphilis contracted during the experiments. To date, they have received no help or assistance from the U.S. or Guatemalan governments as reparations for the experiments. In fact, Ramos himself paid for the only medication he received from a private clinic.

While Guatemalans continue to suffer the harmful effects of experiments conducted 70 years ago, the country still serves as a laboratory for the global pharmaceutical industry. Although these days the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and multinational pharmaceutical corporations require that researchers demonstrate their compliance with international regulations by using consent forms in human-subject experiments, local physicians say that ethical problems persist in research practices and the number of clinical trials continues to grow.

Dr. Manuel Gatica, a gastroenterologist who has participated in clinical investigation in Guatemala and works for the Guatemalan Institute of Social Security (IGSS), says not much has changed since the syphilis experiments. “Guatemalans are still being used as guinea pigs in medical experiments,” he told me in an interview in his private clinic in Guatemala City. “The researchers are not injecting them with any disease, but they are exposing them to medications that they are not familiar with.”

Pharmaceutical research grew rapidly in Central America during the 1990s. The upsurge in clinical trials in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) like Guatemala followed the ratification of two agreements: the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines from the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use in 1996 and the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) in 1994. These agreements sought to protect primarily U.S.-based pharmaceutical companies by standardizing regulatory practices to ensure the integrity of trial results, and tied trade agreements to intellectual property rights. Pharmaceutical companies have taken advantage of the fact that LMICs, in most cases, cannot provide universal healthcare to citizens. The companies pursue research in these countries in part because their populations have far less exposure to medications that might confound or bias study results. That bodily history is a benefit to corporations working to comply with Food and Drug Administration (FDA) standards that recommend using trial participants who are not taking other drugs.

According to the NIH-managed website ClinicalTrials.gov, which began collecting data on human-subject experiments in 1997, more clinical trials sponsored by pharmaceutical and biotech companies have been conducted in Guatemala since 2005 than in any other Central American country (252 trials were registered in Guatemala. Panama has the second highest number of clinical trials registered at 219, followed by Costa Rica at 144.) While Costa Rica was once a hub for pharmaceutical research in Latin America, drug trials were suspended there following controversy over clinical trials sponsored by the U.S. National Cancer Institute on a vaccine for the human papilloma virus (HPV). The controversy emerged due to problems with informed consent and non-compliance with local regulations. In short, pharmaceutical companies have increasingly turned to Latin America, particularly Mexico and Brazil, in addition to Guatemala, seeking opportunities to comply with enrollment requirements set by the FDA while keeping research costs down.

Guatemala’s problems with healthcare delivery drive some local physicians to say that clinical research itself is unethical. “The elephant in the room is that in this country there is no access to basic healthcare,” said Dr. Joaquin Barnoya, an Associate Professor in Public Health Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis who has a medical practice and also conducts public health research in Guatemala. “Before we start doing clinical trials on new drugs, we need to ensure that Guatemalans have access to healthcare, in general.”

Following the 2010 public revelation of the sexually transmitted infections (STI) experiments, Barnoya argued in a local newspaper that Guatemala does not have the infrastructure in its healthcare system, nor the educational training in clinical or epidemiological research in its universities, to sufficiently support and critically evaluate pharmaceutical industry trials. His comments set off a firestorm of controversy on the Internet, primarily from local physicians who are collaborating with pharmaceutical companies on clinical research and who claim that the drug trials conducted in Guatemala comply with international standards.

What many Guatemalan physicians who have collaborated with the drug industry do not address is how a lack of access to healthcare can operate as a coercive factor that pushes Guatemalan patients to consent to clinical trials. In fact, many Guatemalans feel compelled to participate in clinical trials in order to simply get ahold of necessary treatments—even if those drugs are still being tested. Public hospitals and health clinics consistently run out of essential medicines. This is particularly difficult for the estimated 75 percent of Guatemalans who still live below the poverty line – although people who can pay for private health services also have difficulty obtaining treatments.

Such problems have only been accentuated in recent years by U.S. trade policy. In particular, Guatemalans’ ability to obtain affordable drugs has been limited by the Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), which stipulates countries must adhere to intellectual property rights as outlined in the TRIPS agreement. These regulatory measures restrict the production and sale of generic drugs. The high cost of antiretroviral therapy to treat HIV infection has been an especially contested issue in Guatemala, as trade agreements with the United States limit access to more affordable drugs for those who need them most. In 2005, when the CAFTA agreement generated heated debates in Guatemala over access to healthcare and medication, then-U.S. Ambassador John Hamilton published a newspaper editorial warning that Guatemala would be excluded from the benefits of the trade deal if they did not adhere to the intellectual property clause.

Not only do Guatemalans lack basic medical treatments, but government regulations have failed to ensure that drugs will be available once the clinical trials end. Sanofi, a French multinational pharmaceutical company, is currently recruiting Guatemalan participants for a study on a drug, known as Alirocumab, which treats chronic cholesterol problems but has been criticized for its high cost. Sanofi did not respond to questions regarding whether participants would be granted continued access to the drug once the clinical trial ends.

Other drugs that have been tested are not on the World Health Organization (WHO) Essential Medicines List, which WHO updates every two years and specifies safe and cost-effective medications that countries need to meet basic health-care standards. The Pan American Health Organization pools the economic resources of member countries to purchase these essential medicines at a lower cost. In addition to research on drugs considered not critical to Guatemalans’ health needs, sometimes the tests involve placebos—an experimental design issue that has caused an outcry from many ethicists who argue that all participants should receive the best form of medical intervention available.

Guatemalans who lack medical attention and medications consent to clinical trials seeking free treatments, but it is not clear that they understand these studies and the implications for their own health. The consent process in a country where approximately 25 percent of the overall adult population cannot read or write—and that number is even higher among indigenous populations and women—poses a marked challenge to researchers. Despite these problems, physicians report that they have received certification with the Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance to conduct clinical research in little more than a day. Although doctors are required to take a course in which they learn about using consent forms, researchers who have completed the course say typical practices do not emphasize how to obtain informed consent, meaning that participants rarely understand the purposes of the study in which they are taking part. The course also instructs researchers to translate consent forms into indigenous languages, but doubts persist about whether or not participants who have had little exposure to medical research fully understand the purposes of the clinical study.

Part of this apparent lack of ethical rigor can be explained by the fact that the Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance’s certification course for conducting clinical trials was designed by the same man who wants to attract foreign investment from pharmaceutical companies themselves. Dr. Leon Arango owns the Centro de Investigación y Docencia en América Latina (Center for Research and Teaching in Latin America, CIDAL)—a Contract Research Organization (CRO) in Guatemala. The main purpose of CROs is to ensure that clinical trials are conducted in an efficient and cost-effective manner. They contract with pharmaceutical and biotech companies to conduct local management of clinical trials and oversee the recruitment of researchers and trial participants. On its website, CIDAL markets the appeal of Latin America as a region by highlighting its “treatment naïve” population, “strict but expeditious regulations,” and strong doctor-patient relationships. The first of these marketing claims holds a cynical truth: populations in Latin America are “treatment naïve” because they generally cannot afford to pay for medications. Guatemalan bodies and “efficient” regulations are both highly desirable.

Arango also served as a consultant in developing Guatemala’s regulatory framework (Normativa para la Regulación de Ensayos Clínicos en Humanos) to oversee clinical trials, produced in 2007. On paper, the regulatory system adheres to international guidelines for medical research, but Arango acknowledged in an interview for this article that the approval process has problems. He complained that the Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance is incompetent and stymies the local approval of clinical trials. He also said that the government is not conducting the routine audits of the independent committees charged with conducting an ethics review of the studies. Repeated attempts to interview a government representative overseeing medical ethics for this article were denied.

Arango also said that the pharmaceutical companies bring drugs into the country that patients would not otherwise be able to obtain. He appeals to pharmaceutical companies to continue to provide drugs to participants in clinical trials, if they are proved effective after research ends. But without regulations enforcing this measure in Guatemala, corporations are the ones who decide whether to shoulder the expense of providing continued treatments to participants—or not.

To be sure, the vast majority of local physicians do not participate in clinical investigations—doctors interviewed for this article estimated that only five percent of Guatemalan health professionals overall are involved in pharmaceutical research. The doctors who do participate in clinical research reap significant benefits. Dr. Gatica, for example, said that one of his colleagues drives five cars and pharmaceutical companies bring researchers to international conferences where they are rewarded generously with cruises and expensive meals.

But even so, such researchers take a backseat to the foreign collaborators. Only rarely are Guatemalan physicians the first author in journal papers. For example, in the July 2016 edition of the industry-funded publication, Current Medical Research and Opinion, a Guatemalan researcher was the last author in a study that investigated a combination drug therapy for hypertension. The first two researchers worked directly for Merck & Co., a U.S.-based pharmaceutical company that is one of the largest in the world. Virtually all Guatemalans serve pharmaceutical companies and foreign scientists in a subordinate position.

The doctors are doing maquila,” said Dr. Carlos Vassaux, a cardiologist who served as the doctor for the U.S. Embassy for a number of years. In calling international pharmaceutical research maquila, Vassaux equated it with the low-cost, poor-paying assembly lines operated south of the U.S. border. “They receive a protocol and the results belong to the company, not to you,” he said. “You don’t even know what happens to those studies.”

One reason why Guatemalan doctors are not participating more directly in research is that the universities do not train medical students in clinical investigation and ethics. The University of San Carlos, the national university in Guatemala, is strapped with ongoing budgetary and bureaucratic constraints. Most of the faculty at the school only work part-time while keeping up with their private medical practices.

Physicians interviewed for this article are not, in principle, opposed to clinical research. They believe that such investigation should be part of medicine. But many say such research should only be conducted in cases where there are no other drugs available for the condition and when the participants are granted complete transparency about the study.

The scandal at the IGSS a year ago demonstrated that the highest offices of government are willing to compromise the health and lives of Guatemalans through contracting with pharmaceutical companies. A year ago, La Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en Guatemala (The International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala, CICIG), revealed that in 2014, the IGSS changed its dialysis supplier to a pharmaceutical company called PISA. IGSS employees, businessmen, and the head of the Bank of Guatemala took kickbacks of at least 15 percent from the contract. These dialysis treatments resulted in the deaths of thirteen Guatemalans. The President of the Board of IGSS, Juan de Dios Rodríguez, was arrested along with seventeen public officials and collaborators. In fall 2015, this scandal sparked widespread protest in Guatemala as part of efforts to force President Otto Perez Molina to step down from office.

During the protests, medical doctors from major public hospitals were leaders in denouncing government corruption. Dr. Jamie Cáceres of San Juan de Dios Hospital said that the government has literally robbed the people of basic healthcare services. He distributed a pamphlet in an August 2015 protest that drew thousands of Guatemalans to the capital; the pamphlet read, “We don’t have medicine, we don’t have diagnostic exams, we don’t have plastic bags for the trash…”

Before President Jimmy Morales assumed office in winter 2016, several media outlets published reports that the Guatemalan government would provide reparations to victims of the 1940s STI experiments. But the victims have still not been compensated. Guatemala’s efforts to persuade the United States to fund a bioethics center, similar to the one it founded at the Tuskegee University, have also not materialized.

Dr. Barnoya had hoped that revelations about the STI experiments would spur conversation about the practice of medicine and research in Guatemala, but he said that the topic has largely been forgotten. Following the international outcry about the STI experiments in Guatemala in 2010, the victims of these experiments also believe that they have been forgotten.

“We are only here because of the pure will of God,” said Benjamin Ramos, the oldest son of Federico Ramos Meza. “We are paying our taxes, but we have been abandoned by the central government.”

Lydia Crafts is a PhD Candidate in History at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.