The second round of renegotiations of the North American Free Trade Agreement started on September 1, under the cloud of almost daily threats by U.S. President Donald Trump to unilaterally end the 23-year old agreement.

In a number of statements, dispatched over Twitter and in speeches at rallies, President Trump has accused Mexico and Canada of being “difficult” in the renegotiations, and threatened to begin the six-month process to withdraw from the active agreement, while continuing to participate in the negotiations for a new agreement.

Most observers and participants are not taking the threats seriously, including Mexican Finance Minister Luis Videgaray, who initially dismissed them as a “negotiating strategy,” but eventually responded with a threat of his own: that Mexico will pull out of the negotiations for a new NAFTA if Trump begins the process to leave the active agreement.

But some in Mexico say they would welcome a unilateral departure by the United States. Victor Suárez, executive director of the National Association of Rural Producers (ANEC), said in an interview that Mexico is in a weak position going into the negotiations, and that the changes needed in the North American trade regime are so profound, a cancellation followed by a new negotiation would be preferable to the current renegotiations.

“Our government is tainted by corruption, incapacity to control organized crime, and a propensity to give national resources away to private transnational companies,” said Suárez, who has been a leading voice in calling for the exclusion of agriculture from NAFTA. “And we face an aggressive, racist, xenophobic government in the United States. In these conditions, a renegotiation would make things worse for the people, so we think that there should be no renegotiation, that NAFTA should be cancelled, and that there should be another treaty to govern North American trade, based on cooperation and complementarity.”

ANEC is one of the over 100 social movements and labor unions forming part of the México Mejor sin TLCs (Mexico is Better Without FTAs) coalition. That coalition led a march on August 16 in Mexico City rejecting the renegotiations as they began in Washington. The march ended at the Secretary of Foreign Relations building, where the coalition delivered a document outlining their demands and their opposition to the model of free trade that underpins NAFTA, and proposing alternatives for a just North American integration.

Mexican labor and campesino movements have been expressing opposition to and demanding changes in NAFTA since talks started in 1990, especially advocating for agriculture to be excluded from the deal. Perhaps most notably, the Zapatista uprising of 1994 was timed to start the day NAFTA went into effect, as Zapatista spokesman Subcomandante Marcos called NAFTA a death sentence for Mexico's indigenous populations. But now that renegotiations are underway, these social movements have no faith that the government of President Enrique Peña Nieto has the desire, or the ability, to defend their interests in the renegotiation.

The renegotiations come at a difficult time for the Mexican government. With presidential elections less than a year away, Peña Nieto wants to avoid having his weakness in dealing with his U.S. counterpart displayed. He is already historically unpopular, with approval ratings in the low teens. Although he is not eligible for reelection, his own unpopularity will likely drag down his party—as well as Mexico's other traditional parties—in the 2018 elections.

The current front-runner in those elections is Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a left-leaning nationalist who has been the leading figure on the Mexican electoral left for a decade, after two unsuccessful presidential runs in 2006 and 2012. López Obrador has criticized free trade, and argued that he could get a better deal for Mexico than Peña Nieto. Specifically, he has said that he would more vigorously subsidize agriculture, which could require changes to NAFTA. On August 18, he told reporters at a rally in Tamaulipas that the renegotiations should be postponed until after Peña Nieto is replaced, calling the current president a “weak leader.”

“It’s demonstrated that Trump is threatening Peña, blackmailing him,” he said. “If Peña negotiates the deal, he could end up selling Mexico to the United States.”

The parties are rushing to finish the negotiations in less than six months—very little time for a trade negotiation of this size—apparently at Mexico's request. Suárez, whom López Obrador designated as shadow agriculture secretary during his 2012 presidential campaign, said that the speed of the negotiations is a strategy to stop NAFTA from becoming an issue in the 2018 elections.

“NAFTA is unpopular in Mexico, and the government doesn't want it to become an issue in the election,” said Suárez in a phone interview. “If the renegotiations aren't done by then, it could become a problem for neoliberal forces in Mexico who want to prevent an electoral victory for Andrés Manuel López Obrador.”

Peña Nieto's determination to finish renegotiations by the new year is decidedly ambitious, and many observers are skeptical that it can be done. U.S. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross told reporters in July that a six-month timeline would be “record speed for any big trade negotiation.” By comparison, the original NAFTA negotiations lasted three years. Many worry that the urgency to finish the negotiations will lead Mexico to acquiesce to Trump's demands.

“It's dangerous that they want to finish the negotiations so quickly,” said Suárez. “Our government is so weak, and if they are trying to negotiate so quickly, they'll be willing to cede all sorts of concessions to Trump.”

The mechanisms of negotiation are also fundamentally undemocratic. Fast-track trade negotiations, where executives negotiate a trade deal in secret and then send a final product to their legislatures, leave no room for popular, or even legislative, participation.

“The Senate can't change a comma on the trade agreement,” said Suárez. “They just have to say yes or no. And since in the Mexican case, the Senate is so firmly controlled by the government, they'll almost definitely say yes to whatever Peña Nieto brings them.”

“A Failed Model”

When NAFTA took effect, it was one of the largest free trade areas in the world, bringing together half a billion people and over a quarter of the world's GDP, according to figures from the World Bank.

In the 23 years since it took effect, total regional trade has almost quadrupled, and U.S. investment in Mexico has grown more than six-fold. But the deal also caused major social upheaval across North America. Cheap grains flowed south from the United States to Mexico, who had historically produced corn and other goods themselves. Their inability to compete with agricultural markets in the United States put small farmers out of business across Mexico, devastating rural Mexico and forcing millions to migrate to the cities and the United States. Meanwhile, U.S. labor unions saw their bargaining power collapse as companies began moving manufacturing south of the border to exploit the cheap labor of newly displaced Mexicans.

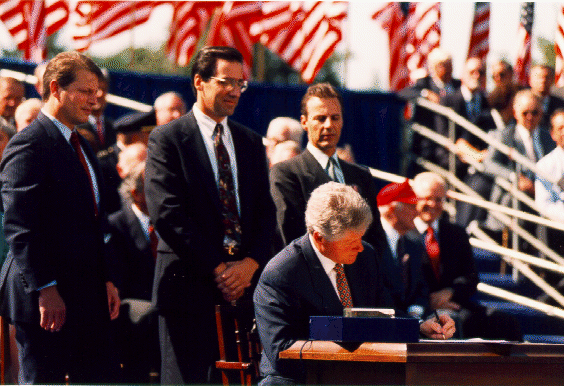

NAFTA was not only sold on the promise that it would increase trade and profits. As the first free trade agreement to cross the north-south divide, integrating countries with vastly different levels of wealth and income, NAFTA also promised economic convergence—the equalization of the massive geographic inequality between Mexico and Canada and the U.S. In the ceremony before signing the agreement in 1993, U.S. President Bill Clinton acclaimed the equalizing benefits promised by NAFTA.

“There will be an even more rapid closing of the gap between our two wage rates,” he said in a 1993 speech. “And as the benefits of economic growth are spread in Mexico to working people, what will happen? They'll have more disposable income to buy more American products and there will be less illegal immigration because more Mexicans will be able to support their children by staying home.”

There are various ways to measure the success of the promise of economic convergence between the countries. But the picture is clear: there has been no convergence in North America. On the contrary, the already-gaping inequality between Mexico and the rest of North America has only grown since 1994. The convergence in wages promised by Clinton has not only not materialized, but the wage gap has actually increased in the past 23 years, according to a study that compared workers in similar positions on both sides of the border. Meanwhile, the gap between Mexico's gross national income (GNI) per capita and that of the United States has more than doubled, as has the gap between Mexico and Canada, according to data from the World Bank.

NAFTA boosters point to the significant increases in trade and cross-border investment, and the modest economic growth that can be linked to the trade agreement as proof of its success. But for Suárez, those numbers don't reflect what's really important.

“Trade should be a means to an end, and that end is to reduce inequality between countries and within them, and NAFTA hasn't done that,” he said. “Inequality has increased between the three countries and within each country, so we can say definitively that the model of free trade has been a failure.”

What's at Stake

Ahead of the renegotiations, the U.S. and Mexican governments published documents outlining their objectives. The documents speak only in general terms, but they clearly show both governments' ongoing neoliberal visions for North American trade. The United States hopes to expand market access for its agricultural goods across NAFTA countries, and “preserve and strengthen investment, market access, and state-owned enterprise disciplines benefitting energy production and transmission,” a clear reference to Mexico's liberalizing petroleum industry. Meanwhile, the Mexican government wants to use the renegotiations as an opportunity to promote fracking and tar sands extraction in Mexico by securing foreign investment. Since then, negotiators have made statements that they intend to put Mexico's 2013 energy reform, which took steps towards privatizing petroleum, into the trade agreement, protecting the reform from a future Mexican administration that may want to reverse it.

During the original NAFTA negotiations, Mexico's state-owned company Pemex still controlled the country's energy resources, and Mexico demanded an exemption from the treaty's energy provisions. That stance spared Mexico from NAFTA's Article 605, the proportional energy-sharing rule, which restricts a country's ability to reduce exports of hydrocarbons to another NAFTA country. One effect of the rule is to compel Canada to export a certain amount of petroleum to the United States, which not only puts Canada's energy independence at risk by threatening Canadian consumers' access to their own country's oil, but also stands in the way of fossil fuel production decreases that would be necessary for the transition to a low carbon economy promised by the Canadian government.

Claudia Campero, representative of the Mexican Alliance Against Fracking, said in an interview that energy proportionality is contributing to the fracking and tar sands boom in Canada.

“As easy hydrocarbons get depleted, it becomes necessary to use non-conventional methods,” she said. “In the Canadian context, that means fracking and tar sands.”

The Pemex monopoly may have protected Mexico from similar measures the first time around, but now that Peña Nieto's government has passed an energy reform and is on its way towards privatizing petroleum and opening it up to private investment, negotiators are aiming to pass provisions that will strip away the remaining barriers on foreign investment in Mexican hydrocarbons. Campero fears that such provisions could accelerate the development of fracking in Mexico, and make it harder for Mexico to transition to renewable energy. The energy reform itself has already opened up much of Mexico's resources to private exploitation, but there's still room for NAFTA negotiators to further erode Mexican energy independence.

“With all the benefits that the energy reform brought oil and gas companies through legalizing the dispossession of territory from communities, it's hard to imagine what else they could want,” said Campero. “And there's still not much information, but considering what we know now about the renegotiations, we are very worried.”

Another North America is Possible

Mexican communities that are opposed to NAFTA don't want to close their country off to the world; the México Mejor sin TLCs coalition not only demands that the current treaty be scrapped, but also advocates for another kind of agreement to govern North American trade.

“We want integration for the people and globalization for justice, equality, democracy, peace and the environment,” their document reads. “We propose a new agreement based on cooperation and complementarity, not deregulation... At the same time, we need to strengthen the internal market and diversify our relationships with the rest of the world.”

The coalition insists that an integration agreement must guarantee human rights and take into account the asymmetries of the countries it covers. Suárez, who helped draft the document, stresses that the goal of opposing NAFTA is not to rebuild barriers between the countries, but to make possible an alternative model of regional integration.

“We reject the false binary of globalization versus protectionism,” he said. “We are not protectionists; we want a globalization that benefits all. And we won't get that from this renegotiation, but from abandoning the failed model of free trade and building a new model from the bottom up.”

Simon Schatzberg is a journalist based in Mexico City. @Simon_Schatz