This article was originally published in NACLA's fall issue, "Prisons, Punishment, and Policing in the Americas."

Scholars and activists have long argued that Puerto Rico functions as a colonial laboratory for the United States. Instances of unethical medical and scientific experimentation in Puerto Rico—including testing of the birth control pill and use of Agent Orange—provide perhaps the clearest examples of the oppressive dimensions of U.S. colonial rule in Puerto Rico and its deleterious effects on the land and its people. Such examples also point to a seemingly unidirectional power relationship between the U.S. and Puerto Rico, marked by U.S. coercion and force over the island.

Yet colonialism is seldom so neat and simple. This understanding of colonial relations, in its attempt to highlight an often hidden history of abuse by the U.S., tends to let local elites and policymakers off the hook. In fact, elites on the island play a central role in facilitating U.S. rule in Puerto Rico and often use compliance with U.S. demands as a tool for consolidating their own political power. Moreover, Puerto Rico has played an active role in shaping U.S. policy. In other words, policy and power may flow from the metropolis to the colony, but that is hardly their only direction of travel.

The history of policing in Puerto Rico over the 20th century goes beyond the image of the island as exclusively a laboratory or policy testing-ground for the United States. This history highlights not only the impact of colonial rule on Puerto Ricans but also how elites and policymakers strategically utilized the island's colonial relationship with the U.S. to reinforce and extend local hierarchies within Puerto Rican society. Often, policing was their most important tool for doing so.

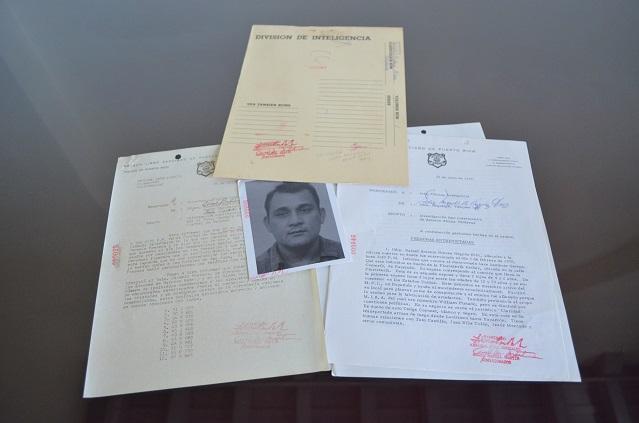

Far from passive agents of colonialism, Puerto Rican political elites and law enforcement officials have long collaborated with U.S. officials to deepen repressive mechanisms both on the island and in the mainland U.S. This collaboration has had devastating consequences for Puerto Ricans on the island and the diaspora. This dynamic is apparent in the history of punitive measures on the island over the past century, from the enforcement of the La Ley de La Mordaza (Gag Law) in the 1940s to joint intelligence operations with the FBI during the Cold War. It continues today through Puerto Rico's hard-fisted approach to crime and implementation of the War on Drugs. Examining these policing measures helps us to understand how local elites have bolstered their own power through repressive measures locally while ingratiating themselves further with a U.S. power structure that has ultimate authority over the island. These examples complicate our understanding of the dense circulations of power within Puerto Rico and between Puerto Rico and the United States.

A Borrowed Framework for Repression

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Puerto Rico’s Law 53, known as La Mordaza, was used to target independence advocates as the Puerto Rican government implemented the island's new “commonwealth” status, establishing the ties between the political agenda of elite Puerto Ricans and U.S. authorities. Key to this new relationship were the new policing measures on the island. In May 1948, Puerto Rico's legislature approved La Mordaza, which made it a felony to advocate the overthrow of the insular government. Actions such as displaying the Puerto Rican flag, singing Puerto Rico's national anthem “La Borinqueña,” writing about independence from U.S. rule, or engaging in any public displays or assemblies that advocated independence were criminalized under the law. La Mordaza was adapted from parts of the U.S. Alien Registration Act of 1940, or the Smith Act, a wartime measure to prevent domestic acts of sabotage and subversion through targeting communist and anarchist organizers, and remained in effect until 1957. The Smith Act provided Puerto Rico's first democratically elected governor Luis Muñoz Marín and the Popular Democratic Party (PPD) with a blueprint for quelling dissidence as they set to strengthen their own power and forge a new political status for Puerto Rico. La Mordaza helped lay the groundwork for the PPD to reform Puerto Rico's status, against the will of pro-independence advocates on the island.

After the passage of La Mordaza, U.S. Congress enacted legislation in 1950 that allowed Puerto Rico to draft its own constitution to reform its political status. Muñoz Marín immediately got to work. Recognizing the barriers to both statehood and independence, specifically the U.S. Congress’ opposition to both, he advocated for Puerto Rico to enter a “compact” with the U.S. that would expand Puerto Rico's capacity for self-governance without abandoning U.S. claims to the territory.

The proposed constitution identified Puerto Rico as an Estado Libre Asociado (Free Associated State), or commonwealth of the United States, which gave Puerto Rico greater autonomy over local affairs, but maintained Washington's ultimate authority over the territory. Political elites supported this move because it allowed the U.S. to show the world that Puerto Rico had been “decolonized” according to the will of the people. Quelling visible public support for Puerto Rican independence via La Mordaza allowed the PPD to make the claim that Puerto Ricans were not interested in full independence but rather preferred greater local governance within the context of continued incorporation.

Independence advocates from the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party saw the status reform as little more than colonialism by another name. Nationalist Party leader Pedro Albizu Campos denounced the proposed constitution and vowed to continue fighting for Puerto Rico's independence. On October 30, 1950, the Nationalist Party mounted a series of coordinated attacks across the island in repudiation of the proposed constitution. The best known incident of the uprising occurred two days later when Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola attacked the Blair House in Washington, D.C., and attempted to assassinate President Harry Truman. In retaliation, the U.S. and Puerto Rican officials ordered aerial bombardments of the towns of Jayuya and Utuado, where pro-independence rebels were active. (Scholar Nelson A. Denis explores the Nationalist uprising in more detail in his 2015 book, War Against All Puerto Ricans: Revolution and Terror in America's Colony.) The uprising was pacified through the combined efforts of the local police, Puerto Rican National Guard, and the FBI, with all fighting coming to an end by November 2.

Click here to read the rest of the article, available open access for a limited time.