The March 11 congressional elections in Colombia marked the post-accord debut of the new Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) political party. Images of former guerrilla combatants voting in civilian clothes and holding red roses, the symbol of the new party, circulated around the world. But the elections were widely considered a disaster for the FARC and a decisive win for the Right: the FARC won just 52,532 votes (0.34%) in the Senate and 32,636 votes (0.21%) in the House of Representatives. Nearly 12,000 of those votes were cast in Bogotá (0.51% citywide).

Though the 52-year armed conflict between the FARC and Colombian state was primarily rural, cities have emerged as crucial sites for post-conflict politics. In Bogotá, the FARC ran on an anti-poverty policy platform and used the congressional campaign to integrate ex-combatants and urban militants into a decidedly urban party. As Alejandro*, a 23-year old militant told me, “The urban is our bridge to peace.”

Though the FARC had initially polled at between 1-2% (and fell far short on election day), party members I talked to in Bogotá were buoyant. They understood their campaign as a triumph in the face of political violence and the state’s failure to fully implement the peace accords. Byron Yepes—a former combatant who is guaranteed a seat in the House of Representatives through the peace accords—said, “This is the first election in the history of our organization. We are just getting started. But we have an important initial base. Our votes are highly qualified. They weren’t bought with money or cement. They are votes of conscience.” A few weeks after the election, Mariana*, an urban militant in her early twenties, reflected, “We built a party even though there is so much stigma and hatred. People in the barrios received us well. We are all very proud.”

A Long Road to Peace

In 2016, the Colombian government and the FARC signed a historic peace accord, ending Colombia’s 52-year war, which killed 218,094 people between 1958 and 2012 and displaced 7.3 million. A confident President Juan Manuel Santos put the peace accords to a referendum vote in October 2016, and, in an unexpected defeat, votes against the agreement outnumbered those in favor by a narrow margin. Just over a month later, Santos pushed a revised accord through Congress, this time without a referendum. The peace accords outline a sweeping transformation of Colombia, including rural development programs, the establishment of a transitional justice court to adjudicate war crimes, crop substitution programs for coca farmers, and a proliferation of post-conflict bureaucracies to manage land restitution, reparations for victims, and historical memory of the war. But the government has only implemented 18.5% of the accords, and it remains to be seen what will happen after the Santos administration leaves office after the May 2018 presidential election. The Special Jurisdiction for Peace, the transitional justice mechanism, began proceedings only a few weeks ago, after facing a series of politically-motivated delays. In March 2017, the disarmament of FARC combatants began, and roughly 10,000 combatants, militants, and their families moved into “concentration zones,” later renamed Territorial Spaces for Training and Reincorporation.

On September 1, the FARC announced its transformation into an official political party, keeping their acronym but changing their name to the Common Alternative Revolutionary Force. The new FARC logo, a red rose with a star, signaled the transformation from las FARC to la FARC. The new FARC promises to make the implementation of the peace accords their primary focus in Congress.

The political reincorporation of FARC ex-combatants guarantees ten seats for the FARC party in the 2018 and 2022 congressional elections—five in the Senate and five in the House of Representatives. The FARC electoral campaign sought to legitimate the guaranteed seats with votes. In Bogotá, the campaign for the House of Representatives aimed for the roughly 100,000 votes necessary to secure one seat, but they fell short by around 88,000 votes.

Unlike most other political parties, the FARC ran for the House of Representatives with a “closed list,” meaning voters chose not an individual candidate but voted for a ranked party list of candidates. Byron Yepes (Jairo González Mora)*, a former commander of the FARC’s Bloque Oriental, headed the list for the House of Representatives in Bogotá. Part of the FARC’s national leadership, Yepes is one of the five FARC members guaranteed a seat in the lower chamber through the accords. Following Yepes on the list were two other former combatants, Sergio Marín (Carlos Alberto Carreño Marín) and Valentina Beltrán (Luz Mery López). The rest of the list was a combination of ex-combatants, militants, and activists drawn from the Clandestine Communist Party of Colombia, an underground FARC-affiliated political party; the Bolivarian Movement, a more loosely organized grassroots movement; and Marcha Patriótica (Patriotic March), a rural people’s movement that emerged in 2012 and has since allied with the FARC. Aside from Yepes, Marín, and Beltrán, the list was young—primarily in their late twenties to mid-thirties, and included former university student organizers, urban environmental justice activists, union organizers, human rights lawyers, and teachers.

A public reckoning with violence of the recent past followed the FARC’s first political campaign. A former combatant recently accused Yepes of forcing her to have an abortion. Beltrán served six years in prison on charges of coordinating urban guerrilla activity in Bogotá. For the candidates I followed, including Yepes, Marín, and Beltrán, the campaign was not only about getting votes—after all, the first 100,000 or so would go towards legitimating Yepes’ guaranteed spot—but a political exercise in reconciliation. It was a chance to go into the streets and talk to people. As Elena*, an ex-combatant on the list said, “it is important for people to see that we are human, that we are carne y hueso” (flesh and bone).” She continued, “And the truth is this: some of the things we did are irreparable.”

Poverty Politics in the Post-Conflict City

People often say that in Bogotá they “don’t feel the war.” Yet Bogotá’s peripheral neighborhoods are built and populated by displaced people, victims of the armed conflict fleeing rural warfare. It was these neighborhoods—overwhelming poor and migrant—that the FARC focused their first urban political campaign.

On January 27, the FARC launched their campaign in Arborizadora Baja in Ciudad Bolívar, a southern peripheral neighborhood of Bogotá. The choice of Ciudad Bolívar was symbolic: most political parties launch campaigns from downtown—from “the heart of power,” as one ex-combatant put it. At the launch, then-FARC presidential candidate, former military commander Rodrigo Londoño, known as Timochenko, said, “it is only by liberating the state from the hands of the old political class that the poor people of this country can have a future.” The FARC framed their entrance into Colombian politics as an extension of the war they waged as a Marxist-Leninist peasant insurgency that began in the 1960s demanding rural land reform.

But how can they translate the politics of a rural army into a policy platform legible to Colombia’s urban majority? The FARC attempted to solve this dilemma by broadly framing their campaign around the right to the city. As Timochenko said at the campaign launch, “every night, from these hills, the people of Ciudad Bolívar look out at that other Bogotá, as if it was a lake of stars. The Bogotá of booming progress, the Bogotá that has always been denied to them. Everyone has a right to know and work towards that Bogotá.”

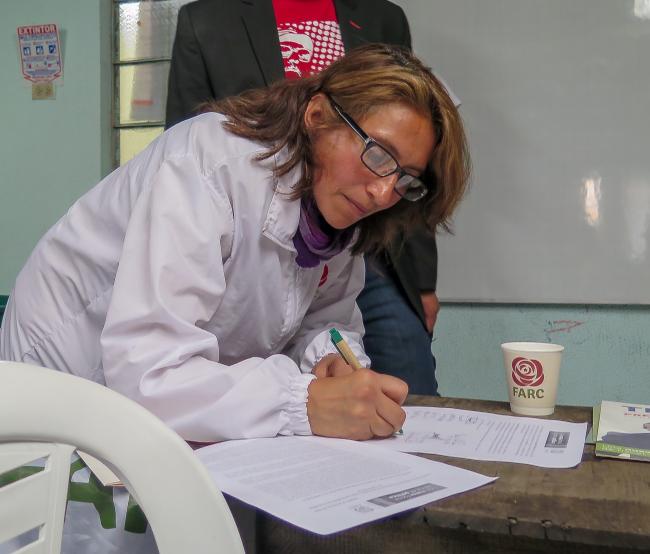

Instead of competing with other Left political parties in middle-class neighborhoods of Bogotá, the FARC campaign focused on peripheral neighborhoods and on the working poor, the “voters who don’t vote.” The FARC’s Bogotá campaign relied on community organizing in these neighborhoods, and on alliances with unions, youth organizations, and victims’ associations. On weekends and in the evenings, FARC candidates met with each group and signed “pacts” formalizing promises from the new party. They went door-to-door and walked busy streets and urban markets, handing out flyers and talking to people. Some just walked away, others pointedly ignored them, and others argued. Most just quietly took the flyers.

In Bogotá, the campaign’s four-point policy program promised to fight for the implementation of the peace accords, particularly reparations for victims. It called for a series of pro-poor urban initiatives, including basic income grants, subsidized transport for students, seniors, and those with disabilities, universal and intercultural health care, and universal public education with affirmative action for Afro-Colombians, indigenous people, and victims of the armed conflict. They also proposed state pensions for domestic workers, stay-at-home mothers, and family members who care for kin with disabilities. The third point called for an end to political corruption and new infrastructures for citizen participation. The fourth point proposed urban measures against climate change and the protection of parks and reserves within the city.

The process of integrating the rural experiences of ex-combatants—recently disarmed in the rural transitional zones and accustomed to giving and following orders—and young urban militants, who have operated within more flexible movement structures, has been complex. As one militant explained to me, “We are learning to work with people who have spent the last twenty years getting up at 5 AM to sing revolutionary songs and do military exercises. ”

In recent months, ex-combatants have relied on militants to build a political party with a strong urban policy platform. As Sandra, a 23-year old Bolivarian Movement militant explained, “We are the ones who know the neighborhoods.” Urban militants organized free breakfasts and community meetings, music nights, and study groups. Alejandro, a 23-year-old militant from Bogotá explained, “They [Colombia’s political class] think we are all campesinos without education who just arrived in rubber boots to set up a political life. But that’s not true. We have always been here. We are the link between the FARC and the rest of the country.” Though the FARC’s base of support is widely assumed to be rural, cities—including Bogotá—ran the most successful campaigns. In Bogotá, the greatest number of votes came from Kennedy, a working poor neighborhood south of the city center.

Victor* is an ex-combatant from Buenaventura, a majority Black city on the Pacific Coast who was recruited into the FARC as a teenager. He has spent the last three years in a southern neighborhood of Bogotá, doing what the FARC calls trabajo de barrio—community work. He is now 27 and serves as a liaison between the party and victims of the armed conflict in his neighborhood in southern Bogotá. When I asked him about the purpose of the campaign, he replied: “The government has always made Colombians believe that war is only when you take up a gun and shoot at someone else. But in the city, there is a war that is much more difficult than the war in the monte (mountains)…it is a war for water, a war for electricity, a war for public services, a war for food, a war for a fair wage, a war for housing. It is a much more complex war than the war we fought in the monte. As an organization, one of our main purposes—and one of our greatest challenges—is to mitigate this urban war.”

Yet FARC ex-combatants are entering post-conflict Colombian politics as perpetrators of wartime violence. Though the majority of atrocities were committed by right-wing paramilitaries, a long-running media campaign (supported by U.S. military and aid money) successfully framed guerrilla insurgents as criminal terrorists. Before a pact-signing with victims of the armed conflict in the neighborhood of Usme, a man approached me and a group of FARC candidates—conspicuously dressed in crisp white jackets with the emblem of the red rose—and started screaming. “Sons of bitches”,” he yelled. “I’ll kill you. You all deserve to die. Assassins! Murderers!” The candidates stood quietly. Afterward, one of the bodyguards—a former combatant from the Pacific Coast said, shaken, “sometimes I forget how much people hate us.”

Like the failed referendum on the peace accords, this year’s elections are charged with hatred for the FARC and anxiety about the rise of “Castro-Chavismo”—shorthand for the potent specter of Cuban and Venezuelan state socialism (especially effective given the economic catastrophe unfolding across the Venezuelan border). The leading right-wing presidential candidate, Ivan Duque of former president Álvaro Uribe’s Democratic Center Party, has promised to revise elements of the peace accords. Along with fear of a socialist state, the Right mobilized against the historic gender provisions of the peace accord, which recognized the gendered violence of war and the economic, social, and cultural rights of women and people with “diverse sexual orientations and identities.” As a billboard for right-wing congressional candidates in Bogotá for the recent election read: “We will protect your family from Castro-Chavismo and gender ideology!”

A Broken Accord?

The March 11th congressional election—the first since the passing of the peace accords—happened amidst ongoing war violence. Peace talks with the ELN, Colombia’s second largest guerrilla group, fell apart in January. The week before the elections, the Colombian army bombed an ELN camp in Antioquia, killing ten combatants. A significant number of former FARC combatants have refused to demobilize; the Colombian army estimates that roughly 12,000, or 15% of the pre-accord FARC army, will not lay down arms. Since the peace accords were signed in Havana, 28 former FARC combatants have been killed, along with ten party activists and 12 family members of ex-combatants; a civil society research institution estimates that a former FARC combatant is assassinated by criminal and paramilitary groups every six days.

Bodyguards in bullet-proof vests accompanied high profile members of the FARC-Bogotá campaign, but rank and file ex-combatants lived in fear and avoided travelling at night. The FARC faced serious bureaucratic hurdles, too: because the legal representative of the FARC was still on the Clinton List, a U.S. Treasury “black list” of people and companies with ties to drug money, banks refused to open an account for the new FARC party. Eventually, the Agrarian Bank opened an account, but with severe restrictions. On April 9th, the Colombian Attorney General’s Office—following an investigation led by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration—arrested Jesús Santrich (Seuxis Hernández), a high-profile FARC negotiator in Havana, on charges of narcotrafficking. Santrich was guaranteed a spot in the House of Representatives in Atlántico, and his arrest, as well as the D.E.A’s request for extradition, threaten the fragile accords.

Attacks against campaign activities across the country accompanied the assassinations. Protesters pelted Timochenko’s motorcade with rocks in the departments of Quindío, Caquetá, and Valle del Cauca, wounding several people. Right-wing politicians suggested that the attacks were a spontaneous show of frustration that war criminals were entering politics before the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, the transitional justice mechanism that would hold perpetrators of violence accountable, was implemented. But others suggest that members of Uribe’s Democratic Center Party coordinated attacks on the FARC’s campaign. On February 9 the FARC suspended all of their campaigns, citing security concerns. A month later, on March 7, Timochenko was hospitalized for a heart condition and withdrew from the presidential race.

Attacks and threats against candidates and the executions of ex-combatants and party activists echo the political genocide of the Patriotic Union, a political party founded in 1985 after peace accords between the FARC and the government of former president Belisario Betancur. The Patriotic Union participated in elections in 1986, but within a few years, paramilitary and state assassins executed eight congressmen, 11 mayors, 13 deputies, 70 councilmembers, and more than 5,000 party militants, including their first and second presidential candidates. Imelda Daza, Timochenko’s vice presidential candidate, is a survivor of the Patriotic Union massacres. For the past 30 years, she has lived in exile in Sweden.

Though it received just .5% of the vote in Bogotá, the FARC’s urban campaign provided an opportunity for fragile alliances across wartime divisions. Before one campaign meeting in a peripheral neighborhood, a woman grabbed my arm and pulled me away from the group, tears in her eyes. She told me that FARC insurgents had killed her grandfather in the early 1990s, displacing her family from their land in rural Tolima. She raised her children in urban poverty in Bogotá, in a cold peripheral neighborhood that never felt like home. She said, “it isn’t right that they are campaigning. That rose is red like the blood they have on their hands.” And yet, the same woman appeared an hour later at the meeting between FARC candidates and victims. She wanted to know if the FARC could provide legal support to demand victims’ long-promised and never-delivered reparations. Her hands shook as she stood to speak.

Emma Shaw Crane is a doctoral candidate in American Studies in the Department of Social & Cultural Analysis at New York University. She would like to thank Alex Fattal, Vanesa Giraldo Gartner, and Marco Alejandro Melo for their generous and generative comments on this piece. This research is supported by the Social Science Research Council and the National Science Foundation.

*Former FARC combatants use their wartime pseudonyms, as does this article. Legal names are in parentheses.