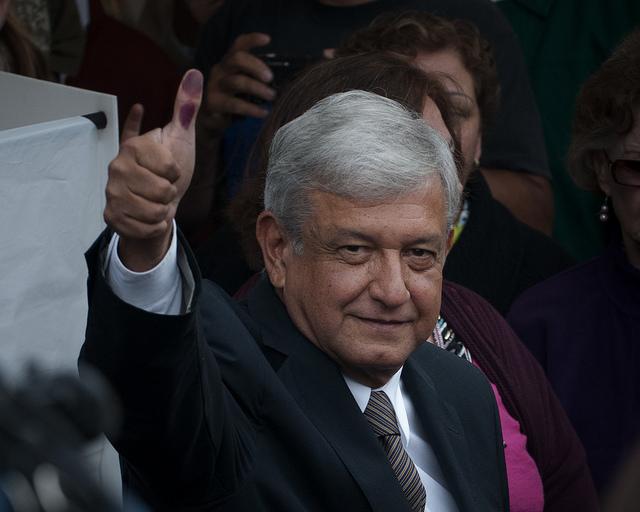

Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s sweeping victory in Mexico’s July 1 general elections came as no surprise, but the absolute majority won by his Movimiento Regeneración Nacional (MORENA) party and its allies in the congressional contests was hardly a foregone conclusion. In an electoral landslide, López Obrador, popularly known as AMLO, pulled in 53 percent of the popular vote. AMLO’s win on Sunday contrasts with his presidential bids in 2006 and 2012 when his competitors barely eked out dubious wins over him.

Trailing AMLO with just 23 and 16 percent of the votes, respectively, were Ricardo Anaya and José Antonio Meade. Anaya ran under a coalition led by the Partido Acción Nacional (PAN), and Meade hails from the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), which led Mexico for 71 years in a quasi one-party system until 2000 and again under current president Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018).

Shortly after midnight on July 2, AMLO delivered a victory speech that made clear his number one priority would be the country’s poor: “For the benefit of everyone, the poor come first,” he declared. At the same time, he suggested that his government would avoid clashes with economic and possibly political elites. Along these lines, he recognized the media for its “professionalism” during the 2018 electoral campaign, in contrast to its “transmissions for a dirty war” during the two previous elections. Similarly, he acknowledged Peña Nieto for his democratic behavior during the election cycle, in contrast with the other campaigns AMLO has run.

AMLO’s cordial words for his adversaries on July 2 have two readings. On the one hand, they reflect his more moderate tone, particularly displayed in the later months of the campaign. On the other, they may reflect the fact that elite groups put up less resistance to his candidacy this time around precisely because they perceive him as less of a threat to their interests.

Sunday’s results also reflect the crescendo of discontent under Peña Nieto and toward Mexico’s political status quo, represented by both PRI and PAN. Various scandals have exposed Peña Nieto’s unethical behavior and deficient leadership, as the nation has experienced a surge in violence and a sluggish economy. Between January 2015 and March 2018 homicide rates nearly doubled, while today the Mexican peso is sharply devalued. Meanwhile the economic repercussions of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) continue to embattle Mexico over two decades after its passage, limiting domestic labor opportunities and creating more reliance on importing products rather than producing them at home—with corn as the most emblematic example.

The results of the congressional elections are particularly important in predicting AMLO’s governance strategies going forward. Many elites have feared that an AMLO presidency would impose top-down revolutionary change. During the campaign, AMLO attempted to assuage these concerns by pledging to obtain majority legislative approval for all major decisions at the same time that he ruled out governing by decree. After two thwarted bids for the presidency and given the young age of his party, it seemed unlikely that MORENA could take control of both chambers of congress.

By the later months of the campaign, the groundswell of support for AMLO’s candidacy indicated that MORENA had a real shot at winning a majority in congress. The reaction of capital was panicked and predictable. In May, Mexico’s benchmark stock index plummeted 7.6 percent, representing the biggest monthly decline in nearly a decade. As Jorge Mariscal of Switzerland-based UBS Wealth Management explained to NBC, “there was an expectation that he would win, but that he would have a check from other parties in congress.”

With such concerns undoubtedly in mind, on June 5, AMLO met behind closed doors with top businesspeople in an attempt to “smooth things over.” Attendees included billionaire Germán Larrea, the CEO of Mexico’s largest mining company “Grupo Mexico,” who had called on employees to vote against the “populist” candidate, claiming that if he won, their jobs would be in danger. A union spokesman of the famed Cananea mines in northern Mexico lashed out at Larrea for his “threatening stance” and called on the electoral commission to investigate the intimidation, a violation of Mexico’s constitution. AMLO described the meeting as “constructive.” The extended list of Mexico’s leading capitalists who question AMLO’s democratic credentials includes Carlos Slim, the world’s seventh richest person, who did not attend the meeting.

During the campaign, AMLO appointed some figures from outside MORENA’s main cadre as leading advisors in specific areas of policy making, as part of an effort to win over or neutralize members of the business community, at least for the time being. It seems to have succeeded. In an attempt to define vague aspects of AMLO’s program, particularly in the area of economic policy, these spokespeople formulated positions that were more moderate than what AMLO had previously embraced.

One key advisor and coordinator of AMLO’s governing program was the agro-industrialist Alfonso Romo, who is now slated to be the president-elect’s cabinet chief. Romo formerly had ties with Opus Dei and supported PRI and PAN governments. Romo assured that AMLO was receptive to the critical positions of the non-MORENA advisors, adding, “we are all changing, and are all learning.” Romo referred specifically to two polemical issues: AMLO’s previous pledges to reverse the privatization of the oil industry and to halt construction of Mexico City’s $13 billion airport, which he considered a waste of resources.

However, advisors like Romo left open the possibility that as president AMLO would build on both Peña Nieto initiatives, rather than rescind them. In both cases, the administration would thoroughly examine existing contracts to root out corruption. But, as Romo said, “if there is no stain of corruption, the bidding process will continue.” In response, the famed leftist writer and fervent MORENA militant Paco Ignacio Taibo II pointed out that Romo’s position conflicted with the party’s stance on privatization, and asked: “In whose name is Romo speaking?”

Similarly, AMLO chose Alfonso Durazo, who had previously served in both PRI and PAN governments, to head the area of citizen security. During his campaign, AMLO proposed to grant amnesty to those outside of the law if they promised to avoid future criminal activity. Durazo quickly backtracked on AMLO’s statements, ruling out blanket amnesty for violent crimes, and assuring the public that key decisions would only be made on the basis of congressional approval and a national debate. He also pointed out that an AMLO government would honor Mexico’s international obligations regarding crimes such as kidnapping. Finally, Durazo promised that all measures along these lines would involve consultation with relatives of victims of drug violence. Durazo’s qualifications might come into conflict with alternative efforts to reduce crime and violence—AMLO recently expressed his support for a Catholic bishop’s initiative to negotiate with drug kingpins in Guerrero in order to reduce violence.

AMLO’s amnesty proposal was a logical response to failed militarized efforts to combat violence associated with drug activity in Mexico. The administration of Felipe Calderón (2006-2012), which launched the country’s drug war in 2006, helped along with U.S. funding as part of a program known as the Mérida Initiative beginning in 2008. Mérida increased funding and equipment for Mexican armed forces and police, and involved bringing Mexican military forces into everyday policing operations. This led to increases in human rights abuses and violence by the armed forces as well as by the drug cartels, as their membership splintered, vied for power, and diversified their income streams. AMLO has advocated a reorientation of government efforts toward focusing more on domestic crime and less on international drug trafficking. His central argument is that the virtual state of civil war in various regions of the country warrants a drastic change in strategy.

Foreign policy is the area where a break with the recent past seems most certain. AMLO’s future Secretary of Foreign Relations, Héctor Vasconcelos (son of José Vasconcelos, an iconic figure of the Mexican Revolution) has promised to uphold “the historic principles of Mexico’s foreign policy,” meaning it will maintain normal relations with nations that Washington attempts to isolate. Over the last two decades, the Mexican government has abandoned that policy, first with regard to Cuba and more recently Venezuela. Vasconcelos also suggests that Mexico reconsider the participation of Mexican soldiers in UN-sponsored peacekeeping missions, an activity which Peña Nieto expanded in order to—according to political scientist Rafael de la Garza Talavera—“reinforce his image as a winner among fellow countrymen and international public opinion.”

When it comes to Venezuela, even while Valsconcelos pledges not to criticize that nation’s “internal matters,” AMLO has called for the liberation of opposition leader Leopoldo López. Even so, AMLO’s foreign policy has the Washington establishment and its allies worried. Miami Herald columnist Andrés Openheimer has expressed concern that AMLO’s foreign policy will signify a setback for Venezuelan democracy as the Lima Group, which serves as a forum to condemn the Venezuelan government, will possibly lose “one of its biggest and most active members.”

During the 2018 presidential campaign, AMLO softened his criticism of NAFTA. In June, AMLO joined Anaya, Meade, and Peña Nieto in rejecting Trump’s threat to negotiate separate treaties with Canada and Mexico as well as the tariffs Washington placed on steel and aluminum imports. Nevertheless, his position on NAFTA remains critical. AMLO has stated that he prefers to leave NAFTA as is than accept a worse deal, but in any case he stands by the idea that the government should stimulate national production to reduce its dependence on U.S. products. His government will include the issues of immigration and the construction of a border wall in the negotiations over NAFTA.

Some Mexican leftists have criticized AMLO, MORENA, and its predecessor party for watering down or abandoned previous leftist positions. The far-left, such as the Trotskyist party Izquierda Revolucionaria (IR), has criticized MORENA for its alliances with less militant organizations and individuals “subordinating all of the party’s actions to electoral campaigns.” Nevertheless, the IR calls on its members to work within MORENA and provide AMLO critical support.

Most MORENA militants who consider themselves on the left support AMLO despite reservations, as I wrote in NACLA’s summer issue this year. As Jorge Veraza, a foremost Mexican scholar of Marxism, told me, “members of MORENA’s leftist current generally feel that López Obrador’s time to govern has come; they hail his courage for having rejected the efforts of PRI and PAN to create a ‘national consensus’ as a cover for advancing a neoliberal agenda.”

The conservative ascendancy across the globe and the setbacks suffered by Pink Tide governments in the region have undoubtedly influenced AMLO to tone down his rhetoric and modify stands in order to become a viable candidate in Mexico. It is precisely for this reason that the significance of AMLO’s triumph cannot be underestimated, as it contrasts so markedly with electoral trends elsewhere. Although AMLO is unlikely to undo the neoliberal reforms that found maximum expression in the Peña Nieto administration, his proposals point to potentially far-reaching changes. For instance, the annulment of contracts with multinational oil firms (or construction companies working on the Mexico City airport) that violate national legislation and interests or contain elements of fraud clashes with what neoliberal apologists consider to be the sacred rights of private capital. Furthermore, AMLO’s refusal to endorse the international condemnation of the governments of Venezuela and Cuba goes a long way toward discrediting the interventionism promoted by the Trump administration. AMLO’s amnesty proposal and support for scaling back or eliminating the Mérida Initiative also represent an assertion of national sovereignty which distances Mexico from the colossus to the north.

While some leftists pejoratively characterize AMLO as a “social democrat” or “center-leftist,” those on the opposite side of the political spectrum consider his program to be obsolete. Former leftist Jorge Castañeda, a campaign coordinator for presidential candidate Ricardo Anaya, has critiqued AMLO because “López Obrador believes in outdated nationalism, outdated statism, archaic protectionism and archaic subsidies in all spheres.” Nevertheless, context is everything. Since the fall of the right-wing dictatorships in South America in the 1980s, no particular economic model has proved successful in the region. In a world dominated by neoliberals and right-wingers, AMLO’s election provides hope and opportunities for progressives in Mexico and elsewhere.

At the same time, AMLO’s effort to convince powerful elite interests that he does not represent a systemic threat faces limits. As we’ve seen in Brazil and other Pink Tide governments, many of those who defend the established order will promote destabilization and regime change as soon as leftist governments confront serious economic difficulties and an erosion of political support. The only effective response is mobilization of the popular sectors, which a government that reneges on promises of popular and nationalistic reform and change will not be able to count on.

The majority vote achieved by AMLO and the MORENA coalition on July 1 will facilitate actions in favor of much needed change for Mexico. The pro-establishment discourse, however, now points out that Mexico’s federal system requires a majority at the state level – which the MORENA coalition lacks —to be able to enact far-reaching legislation. Congressional control will certainly help, but will not guarantee that AMLO can fulfill the expectations he’s built for the Mexicans who put their faith in him on July 1.

Steve Ellner has been a NACLA contributor since the late 1980s. His most recent article, “Implications of Marxist State Theory and How They Play Out in Venezuela” appeared in the journal Historical Materialism. He is the editor of the Latin American Perspectives issue “Latin America’s Progressive Governments: Separating Socio-Economic Breakthroughs and Shortcomings,” slated for January 2019.