Click here to read this article in Spanish.

On May 24, 2018, Gabriel Angel Rodriguez Patiño was returning home from the village center of Briceño, a municipality in northern Antioquia, Colombia, to the vereda (rural hamlet) of Cucurucho, where he had lived for 39 years. Like his companions Javier and Andrés*, he was on mule. The three men plodded along talking as dusk fell and the shadows lengthened along the rocky route. At 6:20 that evening, they approached a group of soldiers standing along the path, armed with semi-automatic rifles. Javier, who went first, greeted them in typical Antioqueño fashion: “Que más, mis amigos?”

In response, the soldiers opened fire. The mules took off running, throwing Andrés and Javier to the ground—probably saving their lives, the men told me later. Gabriel Angel was shot in the chest and died instantly. The soldiers immediately apologized. It was a mistake, they said—they thought the men were part of a Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) dissident group that had begun operating in the region after a small number of guerrillas pulled out of the group’s peace process with the Colombian government after it didn’t hold up its end of the bargain. The group has since grown rapidly with fresh recruits.

Gabriel Angel, like many campesinos in the region, had raised cattle and grew coffee. Also, like most in the area, he had cultivated coca until voluntarily pulling out all his plants about six months earlier as part of a pilot coca substitution program in Briceño, implemented in May 2017. Briceño had been chosen as the place to launch the pilot substitution program and christened the Laboratorio de Paz (Peace Laboratory). Before the program, 90% of Briceño’s economy had been based on coca, but since its implementation, campesinos have voluntarily pulled out their coca plants. In fact, the day Gabriel Angel was killed, the three men had come to the village center to claim their cash payment of two million Colombian pesos per family (roughly $700 USD), paid every two months for a year.

With the FARC’s disarmament, Briceño, long the site of violent contestation between guerrillas, paramilitary groups, and the Colombian military, is in fact experiencing what some locals describe as an era of unprecedented peace. But major delays in the implementation of productive projects to replace coca have brought the local economy to a standstill, fortified FARC dissidence, and contributed to the tense security situation exemplified by Gabriel Angel’s murder.

An Indefinite Wait

While families like Gabriel Angel’s have received bimonthly payments for pulling out their crops, other parts of the program to support a transition to other crops haven’t materialized. Aside from the cash payouts, the program also promised that families would receive goods worth stipulated amounts of money to allow them to develop three different productive projects: small subsistence farms; short-term projects in the first year to help them make money after cash payments ended; and additional funding for long-term projects to begin in the second year.

However, in the 11 veredas of Briceño where the program was launched more than a year ago, the cash payouts have ended without any sign of the other funding. Instead campesinos have been left awaiting a bureaucratic process that requires agricultural technicians to visit them multiple times, create an investment plan, combine plans for 700 families, obtain bids for materials, and choose the companies to provide them.

For these 11 veredas, the bidding process for only the subsistence farms, a scant 9% of the promised investment, recently ended, and officials say goods will be distributed within two months. They will have to start the investment plans and bidding process anew for first the short- and then the long-term projects.

Most locals don’t understand the intricacies—they only know that the state has kept them waiting as their money runs out. Gabriel Angel, in fact, was one of the more privileged campesinos, in that his family had land, coffee, and cattle. The majority of farmers registered in the substitution program don’t own land, working instead as tenant farmers—though the peace agreement also provides for the redistribution of land to campesinos who don’t have it, also yet to be delivered.

Before uprooting his plants, Rodrigo cultivated coca on a rented plot. As was customary, he gave 10% of the profits to the plot owner, he explained to me in June. A harvest every three months provided more than enough for his family of six. If he needed it, he could jornalear (day labor) for 50,000 pesos a day ($17.50), usually picking coca. Now he says the wages for a jornal have plummeted to 20,000 pesos ($7) and work is nearly impossible to find.

When the cash subsidies first began, Rodrigo bought clothing and other so-called luxuries for his family. When he realized government aid would be delayed, he began to budget his money carefully, he told me. He was able to buy some land, and plant blackberries with two family members. But now the money has run out, and the blackberries aren’t yet producing. Even when they do bear fruit, Briceño’s unpaved paths mean that transportation costs will cut heavily into profits—not a problem for coca production, when drug traffickers would arrive on mule to pick up coca paste from his house, according to Rodrigo.

Rodrigo says his family plans to stay in Briceño, but to feed them he says he’ll have to make the long and expensive journey to nearby municipalities to look for work. In his vereda, he estimates half of the families have had to leave due to lack of economic opportunity—which, according to public statements by government officials in meetings with the community, is grounds for removing them from the substitution program entirely.

Dissidence Rising

The route that Gabriel Angel took on the day of his death skirts the top of the Cauca river valley, passing fields of corn, coffee, plantain, and yucca, and the occasional small dwelling. Clouds often obscure the river below or even envelop the path in a white mist, but on a sunny day the green on the valley walls is striking, each shade brighter and deeper than the last. But amidst the natural beauty are more sinister markers.

Spray-painted on the blank walls of houses and storage sheds are messages from the dissidents of the FARC’s 36th front, a residual group that has reemerged after the 36th Front disarmed in early 2017. Graffiti on walls proclaims slogans like, “Somos Indestructibles Frente 36” (We are Indestructible 36th Front) and “Frente 36 Limpieza de Paramilitares (36th Front Cleansing of Paramilitaries).”

While the FARC have maintained a constant presence in Briceño since 1981, locals say the municipality’s history of extreme violence began when paramilitary groups arrived to compete with the FARC for territorial control beginning in 2000. The paramilitaries battled the FARC, collaborated with the military—locals told me they openly referred to each other as “cousins”—promoted the cultivation of coca, and killed those suspected of being FARC collaborators or selling coca elsewhere. Essentially no one was untouched by the conflict.

While Briceño does not currently face a paramilitary threat, neighboring Ituango does, particularly in areas where coca still grows, and where the substitution program has yet to begin. There the FARC dissidents of the 36th Front have been clashing with the Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia, a paramilitary group heavily involved in drug trafficking. This supports the most common narrative of the dissidents as criminals who never wanted peace, drawn from the ranks of experienced FARC combatants. This story says they have rejected civilian life, preferring to keep their arms to fight for control of lucrative drug trafficking and illegal mining economies.

However, the formation of the dissidence in Briceño tells a different story. Its leader, known as Cabuyo, participated in the peace process, disarming and working in a program to remove landmines from the vereda El Orejón in Briceño. Multiple locals who know Cabuyo told me he left the peace process out of anger over the government’s failure to comply with the accords, including the substitution program.

More disturbingly, local leaders who wished to remain anonymous say the bulk of the group’s strength comes not from FARC veterans, but from new recruits drawn from disillusioned local youth. Locals told me that the week before they killed Gabriel Angel, the Colombian military engaged the dissidents not far from Cucurucho and killed four enemy combatants.

Eduardo, who lives near the zone where the group has its most consistent presence, told me that far from hardened fighters, the combatants killed were all teenagers who had joined the group since the FARC disarmed. He estimates that of the 200 to 250 members of the dissident group, only four were FARC members before the peace process. The rest are young men, around 15 to 20 years old, who, with the collapse of the coca economy, have been left without other options.

Ignacio Jaramillo, a leader from a different vereda, says a lack of economic opportunity is driving participation in the dissidence: “The great majority aren’t from the FARC, just the commanders. They’re kids from coca-producing families, so they would have been working in the coca, but not anymore,” he said. “The group is fueling itself from that void, that crisis that families are experiencing. Families have four hungry kids. [The dissidents] say ‘come, we’ll pay you, give you food.’”

But hunger and lack of opportunity aren’t the only things driving youth to join. Community leaders say the dissident group harnesses fear and anger against state institutions, including the military and the government’s failure to follow through with the promises of the peace process. The people of Briceño understand the substitution as a quid pro quo agreement: we pull out our coca plants, in exchange, the government gives us the necessary support to develop new economic activity. They feel cheated, tricked into pulling out the coca plants that fed their children based on the expectation of government aid that has yet to materialize.

A long history of state absence fuels this mistrust of the government. In the areas where they had control, the FARC performed governmental functions, including dispute resolution, punishing criminals, and organizing the maintenance of local paths. A day after Gabriel Angel’s death, I spoke with Ana, a leader in a nearby vereda. She related the killing directly to the transition from the control the FARC previously had over this part of Briceño: “The state was never there. [In a meeting with the government] we asked who was going to occupy this place, to take over the power the FARC had. They said the fuerzas públicas (public forces). And this is how they occupy it.”

Popular Resistance

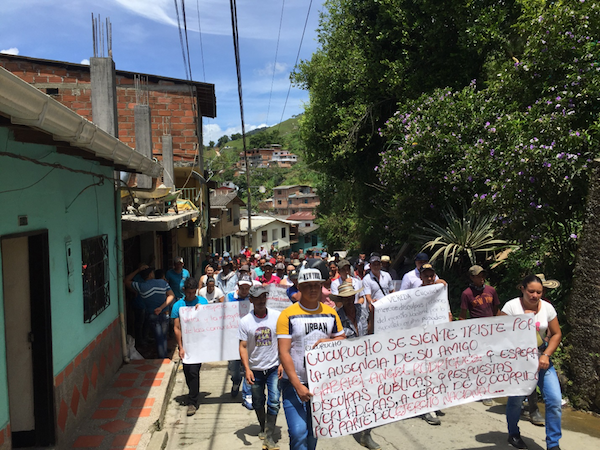

On June 23, nearly a month after the murder, the narrow streets of Briceño’s sun-soaked village center were filled with the cries of more than 100 campesinos. Behind their calls for peace, truth, and the recognition of Gabriel’s place as a brother of the community were deeper issues around the institutional and media response. One of the major complaints of the protest was related to an El Colombiano article that claimed Gabriel Angel was unknown in the community and that the three campesinos had failed to respond to an order to halt—the latter an assertion from an army press release. This misinformation contributed to a long history of stigmatization of campesino populations in areas occupied by the FARC. “All our lives we’ve been marked as guerrillas,” a local leader said at a pre-march rally.” Throughout the action, locals affirmed that Gabriel Angel was their brother, a well-respected hardworking member of the community, and not a guerrilla.

Peace was also a unifying theme. At the rally, another leader said, “the communities are living up [to the coca substitution agreement] because they’re tired of violence. We want to move from the illegal to the legal… We don’t want violence; We’ve had enough already.” With a year having passed without productive projects, locals fear that a tenuous peace is already degrading, that campesinos will go back to planting coca, bringing back armed groups, violence, and stigmatization.

The national and international context also give cause for concern. In the June 17 presidential election, Colombia chose rightwing candidate Ivan Duque, who has come out publicly in support of aerial fumigation to eradicate coca crops, now with drones. The Trump administration has also cited an overall increase in coca production in Colombia to support a return to fumigation, banned in Colombia since 2015 over health concerns. Local leader Jhon Jairo Gonzalez, who as a coca farmer in 2008 suffered through the fumigation of his crops, says that the promised investment in local projects is needed to demonstrate that crop substitution, not fumigation, is the answer. “Where there was fumigation, they burned all kinds of crops, damaged the water, and made us sick. Because no investment arrived, what did we do? People weren’t going to endure hunger,” he said. “We planted coca again. Now with substitution, we pulled out the coca, put everything into this. We’re the pilot plan. If we fail, what is this going to show on an international level? That the substitution project doesn’t work.”

An Uncertain Future

An hour after the march ends, I sit in a cafeteria watching Germany play Sweden in the World Cup with Manuel, a young man who came to the village center for the protest. His family has plantains, but without the influx of money from coca, people are growing their own food and there’s no market for their crop. Briceño is isolated enough, two hours on unpaved routes from the main highway, that sending produce elsewhere isn’t economically viable. His plantains are rotting as his family’s money runs out. “What can we do?” he asks. I have no answer.

Amidst the excitement of the game, he calls over two friends to show me their hands. The men previously worked as raspachines, literally “scrapers,” the word used to refer to coca-pickers. The best raspachines bend over the plant, grip the bottom of a stem, and alternately draw each hand along the branch back towards the body in a quick motion not dissimilar to rowing a boat, taking the leaves while leaving the branch intact. The novice picker suffers cuts and bleeding before developing thick callouses. Despite having been raspachines most of their lives, the men’s hands have grown soft; it’s been a year, they say, since they’ve been able to find any kind of work, a year since uprooting their coca. They’re all enrolled in the substitution program but have lost faith in productive projects ever arriving. None of them want to go back to the coca, but neither will they let their families starve. They agree: “Briceño will fill up again with coca.”

Local leaders say the fact that Gabriel Angel’s death elicited such a strong and public reaction is itself a sign of progress; when untold numbers of campesinos were murdered in times of guerrilla and paramilitary control, people were too scared to speak up. The peace agreements have opened a space for campesinos to demand state support, security, and social investment that have never existed in marginal areas of the Colombian countryside.

But as these demands are ignored or pushed through bureaucratic channels, the optimism and tranquility that came with the peace process are ending. Briceño was supposed to provide a tangible example of how to transition from FARC to state control, coca to legal crops, and violence to peace. Instead, without a radical and rapid change, it may end up a cautionary tale.

Alex Diamond is a Ph.D. student in Sociology at the University of Texas at Austin. His research focuses on the implementation of the peace accords between the FARC and the Colombian government and the transition in areas previously under insurgent control.

*Use of first names reflect pseudonyms used at sources’ request