Read a Spanish verion of this article here.

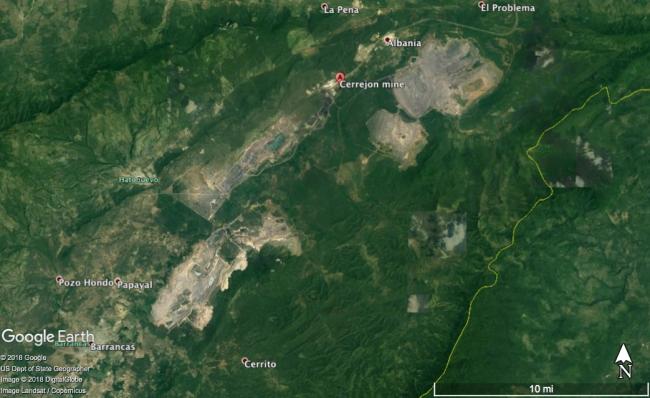

We spotted the deep, wide gashes cut into the earth of Colombia’s coast from 20,000 feet in the air. The extraordinary birds-eye view of the massive pits was our first encounter with La Guajira’s open-pit coal mine, Cerrejón, and our first clue that coal is not just “big business”— it is colossal business. From our point of view, Cerrejón’s visual impact also made us—two Puerto Rican anti-coal activists on a mission to understand the environmental, social, and cultural impacts of coal extraction—contemplate our own smallness.

The word used in La Guajira to refer to the open coal pits is “tajo,” Spanish for cut or gash, because the pits look like wounds carved into the surface of the landscape. A deep tajo is also called a herida (wound), a testament to the profound physical and emotional suffering the communities in La Guajira endure. Cerrejón, the world’s largest open-pit coal mine, is owned by multinational mining giants Anglo American, BHP, and Glencore. Its arrival to the region nearly four decades ago has caused irreparable harm to the environment, landscape, and the people who live there, including upending their farming livelihoods, causing widespread air and water contamination, diverting streams, and cutting the community off from its water sources.

Richard Solly from the London Mining Network aptly described the scale of Cerrejón’s operation as “massive open holes, where coal is gouged out using enormous mechanical shovels. Whatever is on the surface—woods, farmland, villages—has to be erased in order to open up the pit and get at the coal.”

Despite being resource-rich, most of the inhabitants of La Guajira, who are primarily Indigenous Wayúu and Afro-descendants, are poverty stricken. In the first three months of 2018 alone, 16 Wayúu children died from malnutrition and dehydration. A resident we spoke with referred to the area as a “pueblo de minas, pueblo en ruinas” (town with mines, town in ruins), to refer to La Guajira’s staggering levels of poverty, high rates of malnutrition, and infant mortality.

The adverse health effects impact not only residents in communities close to the mine, but also the mine workers themselves, including respiratory illnesses, cancers, bone atrophy, and frequent injuries.

The burning of coal to generate electricity has dire consequences on the environmental and individual health of communities located close to these plants. Finally, the disposal of toxic-coal ash causes birth defects, miscarriage, and cancers. This creates a sort of “death cycle” in communities and environments wherever coal is extracted, burned, and disposed.

We traveled to La Guajira with two Colombian social organizations, Fuerza de Mujeres Wayúu (Strength of Wayúu Women) and Indepaz. We were fortunate to join Aviva Chomsky, along with delegates from Witness for Peace. Over the course of four days, we visited five communities and heard testimony from six more. We also met with members of Sintracarbon, the mineworkers’ union, and attended a meeting at the Cerrejón mine with the management team, community leaders, and union representatives. What we witnessed and heard reaffirmed to us that coal is anything but clean energy—a dirty business that must be ceased.

Loss of Land, Loss of Culture

“We refer to the earth as Mother Earth because she has nourished us through the generations, ” Rogelio Ustate Arrogoces, who comes from the displaced community of Tabaco, tells us one sweltering August afternoon during our visit. “We ethnic communities, Afro-descendant and Wayúu, have always lived off of agriculture, fishing, hunting, and from herding our animals. We have a spiritual anchor to our land,” he explains.

Tabaco is a community comprised of about 700 Afro-Colombian residents who were forcefully evicted from their land by Cerrejón in 2001. Despite promises to resettle the community, for 17 years Cerrejón has left them displaced. Stripped of their homes, many have been forced to migrate to cities or out of the region altogether. “Because we have been displaced, we have lost our sacred places, our meeting places, we have lost our ancestral medicine,” Rogelio says.

Ustate Arrogoces’ words reflect the importance of traditional and local ecological knowledge for the well-being of communities and the impacts of displacement on people intimately connected to their lands. “In losing our ancestral medicine we have lost part of our lives ,” Rogelio explains. “In being forcefully displaced we have fallen into extreme poverty.”

His comments speak to a loss of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), or local knowledge about a natural environment that forms an intrinsic element of a social group’s culture that endures, even as it changes and evolves, through generations. Such ecological knowledge is often held by peoples considered to be indigenous to a place, usually in resistance to colonialism and expansionism. These cultural traditions are grounded in a specific territory, landscape, and natural resources. This knowledge is preserved and passed down through oral and written traditions and in spiritual and cultural practices, such as in art and crafts, song, dance, ceremonies, planting, fishing, foraging, and in the preparation of traditional medicine and foods. Essential to the vitality of ancestral and traditional ecological knowledge is the maintenance of language, access to the environment and natural resources, intergenerational continuity, and the ability to practice and pass down cultural traditions without restriction.

Ustate Arrogoces stressed that land is fundamental for Afro-descendant and Indigenous communities, who cannot live out their worldview of collective wellbeing in harmony with nature without a connection to the land. “When we don’t have our land, we don’t have buen vivir (good living),” he says.

In the case of the Afro-descendant and Indigenous communities of La Guajira, the coal mine’s extractive forces have caused irreversible damage to the social fabric of the communities affected, as well as to the natural environment. For Rogelio, the connection between loss of land and loss of culture is clear. “Any negative impacts that exists on our land also impacts our culture and the possibility for the sociocultural development of our community,” he explains. “Territory is a source of legitimacy, confidence, and strength across generations, and the loss of territory also means the loss of possibilities to develop ourselves, and to live.”

The impacts of the mine on this cultural knowledge and spiritual well-being are pervasive. Aura Robles, the authority of the Wayúu community Paradero, explains that the more than 90-mile (150-km) train that runs adjacent to Paradero, and transports coal 24 hours a day from the mine to Puerto Bolivar on the coast disrupts dreams and disturbs residents on a spiritual level. “My mother is a dreamer and the train interrupts her dreams and she is unable to continue dreaming once she is awake,” she says. “And this is upsetting because her dreams are a source of important information for us.”

Contamination of Communities

Water quality and contamination is a major concern for affected communities. La Guajira is a semi-desert region, where water is a precious but increasingly scarce resource. Cerrejón guzzles up nearly nine million gallons (34 million liters) of water every day. After nearly four decades of mining, water sources are contaminated, and unless treated, unfit for human consumption.

Indepaz, a Colombian social justice NGO, has found that the nearby Rachería River’s water contains heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, arsenic, zinc, magnesium, iron, and barium, which endanger the health of flora, fauna, and people. Similarly, they have found that mining has had adverse impacts on the region’s air quality. Coal extraction ejects particulate matter (PM-10) and emits sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide into the air. These contaminants put the region’s population at greater risks of suffering respiratory illnesses and certain forms of cancers.

But mining officials have brushed off the problem, blaming local residents for polluting their own water sources. “The mine says that the contamination of our water results from our animals defecating in the water,” explains a Wayúu community authority in Charito, another community wedged beside the train tracks near Cerrejón, who wished to remain anonymous. “That feels as if they are mocking us, insulting us. How can they say such a thing when we know our animals are not causing the widespread contamination of our water, when our ancestors had animals and the water was not contaminated?”

Wayúu and Afro-descendant community members raised these issues at a recent meeting with Cerrejón itself. They voiced concerns about the lack of access to and availability of clean water for communities while the mine continues to use astronomical amounts of water every day, and accused the company of destroying clean water sources.

Cerrejón representative Gabriel Bustos denied that the mine is to blame for water contamination and scarcity and demanded proof of poor water quality. Bustos refuted the findings of Indepaz’s report on widespread water and air contamination in the region, claiming the mining company has conducted its own study confirming its operations have not caused contamination. He instead accused communities of discarding untreated wastewater into the river and suggested that agricultural runoff could compromise water quality. Community members maintain that the potential pollution of their small-scale farming activities pales in comparison to the toxic impact of the world’s largest coal mine.

During the meeting at the mine, we witnessed the outright disregard for the community’s members’ knowledge and the placing of blame on the community for their problems. Time and again, the mine representatives contested the community member’s ecological observations with “scientific” data. This alienated community members and made them feel as if their knowledge was useless.

This is a common practice for multinational corporations, states, and even the scientific community. These sectors often construe traditional and Indigenous knowledge as “backwards,” “harmful,” “superstitious,” and “uneducated,” as scholars such as Henry P. Huntington, Robert Johannes, and Carlos G. Garcia-Quijano have reported.

Bad Neighbors

During the meeting, several Indigenous and Afro-descendant community members referred to the idea of being a good neighbor, which requires mutual respect, as a reminder to the mining company that has not acted in good faith towards the communities. In turn, the mine executives reminded the communities that the multinational company is not the state and therefore unable to fulfill all the demands made by the communities. An Afro-descendant community member from Tabaco denounced the company’s denial of responsibility.

“You are the ones who removed the communities from their territories, as such you are responsible for providing water to the communities. We had water in our communities and now you have created pits in our territories,” he says. “You cannot tell us we have to fend for ourselves now, we were living peacefully in our territories and you are the ones who came here and removed us from our land.”

Hilda Lloréns is a faculty member in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of Rhode Island. She is the author of Imaging the Great Puerto Rican Family: Framing Nation, Race, and Gender during the American Century (Lexington Books, 2014).

Ruth Santiago is an environmental and community lawyer who lives and works in Salinas, PR. In 2013, she was an Earthjustice fresh air ambassador. She is a recipient of Sierra Club’s 2018 Robert Bullard Environmental Justice Award.