The strength of NACLA has long been its on-the-ground reporting. With a focus on hemispheric politics, political economy, and social movements, our Reports and articles have both considered and steered away from broad considerations of imperialism and U.S. hegemony, analyzing conflicts and developments on their own terms.

Faced with the lack of reliable information on the 1965 U.S. invasion of the Dominican Republic, for example, U.S.- based critics of the invasion—mostly students, many of them veterans of the Peace Corps—reached out to one another to coordinate research on the island and in Washington. The research was empirical, and quickly came to incorporate both interpretation and analysis. Ideological commitment entered into NACLA's reporting, and it did so out of necessity. After the aggression in the Dominican Republic, lack of reliable information led to a search for a credible interpretation of those events, and a way to present its findings in an accessible manner. That necessity gave birth to NACLA.

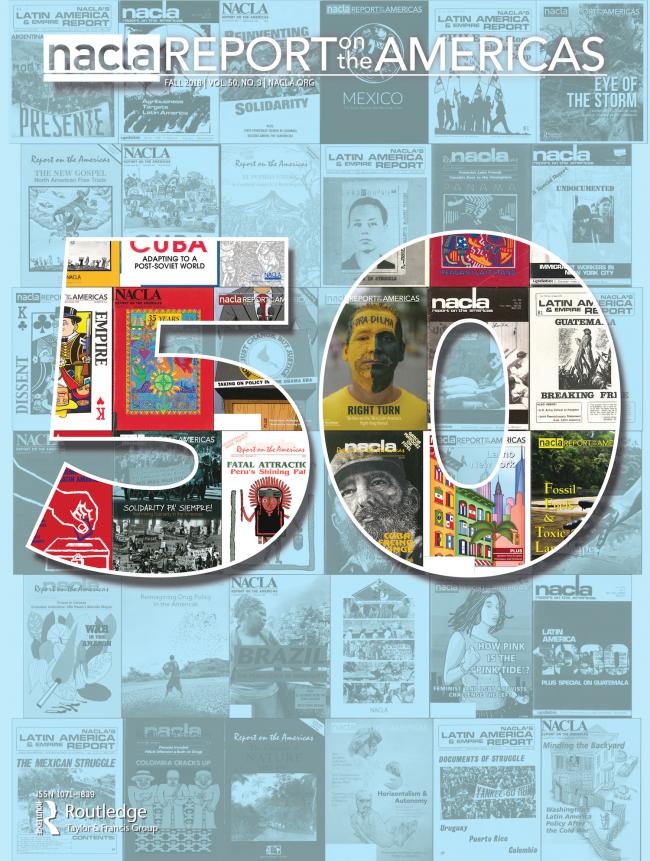

As we complete our 50th year of research, publication, and activism, we look back in this issue of the NACLA Report to where we have been, how we got there, and some of the challenges—and opportunities—that lie ahead.

For some, NACLA's continuous and reliable reportage and research on Latin America has opened the door to an understanding of the underlying dynamics of the region and its relationship with the United States, and provided progressive interpretation and analysis that is grounded in concrete realities. For others, NACLA has created a critical community of diverse activists, academics, and a broad spectrum of progressive strategists and policymakers.

NACLA has also served as a guidepost of sorts for the evolving assumptions and commitments of the North American Left. When we held our first open meetings in New York back in 1966 and 1967, we believed—as did observers and policymakers of all political stripes—that most Latin American and Caribbean conflicts were fought out on the terrain of the Cold War. Coming from the Left, most of our coverage took, as a starting point, the assumption that the key political conflicts—in Santo Domingo and San Salvador, as much as in Santiago de Chile and in Washington itself— were rooted in U.S. imperialism.

Above all, early Naclistas saw the organization they had created as an outpost of anti-imperialism. Over the past half century, that assumption has softened and, to a certain extent, changed, as NACLA, along with many of our companion movements and publications, has moved from an “old left” to a “new left” perspective.

In this 50th anniversary issue, we have pulled some fragments of reporting and analysis out of the Report that represent that gradual transformation. Once we were guided by a belief that history, especially capitalism's history, has a revolutionary logic for leftists to uncover and take part in—principally a struggle between capital and its own industrial labor force. Over time that belief has given way to the notion that the future is unwritten, and that the Left can create its own history in the course of defending social, political, and human rights. Such rights are defensible on their own terms—rights that sometimes but not always come with a revolutionary logic.

Thus for this issue, we have chosen to present pieces that reflect NACLA's evolving style as well as some of the key leftist assumptions that shaped the historical moment in which they were written and published. As readers will see, while the sharpest focus of our first few decades was on the role of U.S. activity and policy in the region, local dynamics have drawn more of NACLA's attention in the more recent past.

In short, there has been a steady shift from the analysis of a single hegemonic system, reflected in the original name of the NACLA Report—“NACLA's Latin America and Empire Report”—to an analysis of a wide variety of causes that have led and not led to a state of affairs we might recognize as “revolution.” Equally important, there has been an unwritten agreement among NACLA writers and editors that reporting and interpretation can and should reflect an understanding that not every Latin American and Caribbean conflict emanates from the United States, that not every militant movement is revolutionary, and that not every radical movement is directed against capitalism.

–Fred Rosen

What’s in the Issue

The issue's format takes on the Sisyphean task of fitting 50 years of history into a single volume. It follows flashpoints in Latin American history and politics over the past five decades, and NACLA's coverage of them, in roughly chronological order. We’ve paired archival excerpts with modern-day reflections by NACLA contributors new and longstanding, which review and introduce these topics, providing an update from the lens of hindsight. While we did not ask our authors to predict the future, it is our hope that these contributions are forward-facing, looking towards a brighter and more just future for the region.

The issue opens with a brief retelling of NACLA's history in an abridged version of Fred Rosen's “History of NACLA” Report from 2003, written at the time of the NACLA's 35th anniversary. Rosen's piece follows NACLA and the issues that fueled the founding of the Congress and magazine: from the invasion of the Dominican Republic to the Chilean coup to 1980s solidarity movements with Central America. It also follows the ideological schisms and splits that NACLA endured, reflecting Naclistas’ deeply-held convictions over time.

Christy Thornton, who since 2003 has held nearly every role imaginable at NACLA, then updates readers on NACLA's history from 2003 to the present. In the last 15 years NACLA's content has grappled with the onslaught of neoliberalism, the wars on terror and drugs, and followed the ebbs and flows of the Pink Tide. Meanwhile, the magazine has struggled to stay afloat amid the explosion of the world wide web. Through it all—and not without sacrifice— NACLA has managed to survive, and even thrive.

The Report then covers the Dirty Wars of the Southern Cone. Steven Volk analyzes the hope and despair of 1970-1973 in Chile, reflecting on a 1970 NACLA interview Saul Landau conducted with Chile's then-president Salvador Allende. Greg Grandin then responds to a 1979 report, “The Long Night of the Generals,” which provides a sweeping look at the terror and chaos wrought by the military dictatorships from Brazil to Bolivia to Uruguay to Argentina and Chile.

1979 also marked when the Sandinistas toppled the decades-long Somoza dictatorship, unleashing an era of Civil Wars across Central America. Our section on these conflicts reprints archival photography by Susan Meiselas from Nicaragua, introduced by Fred Rosen, then offers a longer discussion of El Salvador by Hilary Goodfriend. Goodfriend reflects on Bob Armstrong's 1980 article, “There's a War Going On,” which zooms into the horrors of everyday life in El Salvador against the abuses of the U.S.-funded military. Solidarity played a major role at the time, which Janet Shenk discusses in her sidebar on the delegations she led with NACLA to Central America in the 1980s.

Click here to read the rest of this intro, available open access for a limited time!