“Borderless Economy, Barricaded Border,” written by Peter Andreas in 1999, offers us a freeze frame on U.S. border policy that highlights one moment in a long-developing story that NACLA has covered since the 1970s. What makes it compelling reading for us today is that this snapshot, and the analysis that Andreas supplies to explain it, focuses on a period that we now recognize as a watershed moment in the history of Mexican migration. It was at this juncture that both the laws and the norms that had previously controlled the flow of Mexicans north and south of the border would change in a manner that would substantially erase the relatively free and easy opportunities for legal and unauthorized border crossing that were long part and parcel of the culture of the borderlands. These changes would also crush the hopes of Mexicans who aspired to make a life in the United States without ever abandoning their homeland.

Only ten years earlier, in 1989, when I traveled to Tijuana to study the setting where more than half of all migrants launched their northward journey al otro lado, the atmosphere of free movement and abundant possibility was still in the air. Middle- class Mexicans with border crossing cards regularly shopped for food and fashion in Chula Vista, CA, where the prices and quality of fruit and vegetables exported from Mexico made the trip a break-even adventure. Young Mexicans regularly jumped the fence to party in San Ysidro, CA, returning at dawn to Tijuana. And large groups of 50 or more would-be migrants would mass at the official border crossing and run northward up the southbound lane of Interstate 5 while southbound traffic swerved to avoid hitting them and the Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) agents chasing them on foot managed to grab only the slowest of the bunch.

It was a time when Pedro “Patas,” a man recommended to me as a “coyote's coyote,” enjoyed a record of near perfect success at his trade, often passing his first group of migrants under the fence just after sunset, escorting them as far as San Ysidro where he would deliver them to his associates for the onward journey to Los Angeles, returning to pick up the next group and repeating this routine twice more before dawn. At age 32, he had built a regional reputation for honesty and competence. He charged the standard $300 for the full trip to Los Angeles, and was proud to say that not one of the thousands of people he had “passed” had ever “ratted” on him, because, as he put it: “no one has any reason to finger a coyote who deals honestly with his customers.”

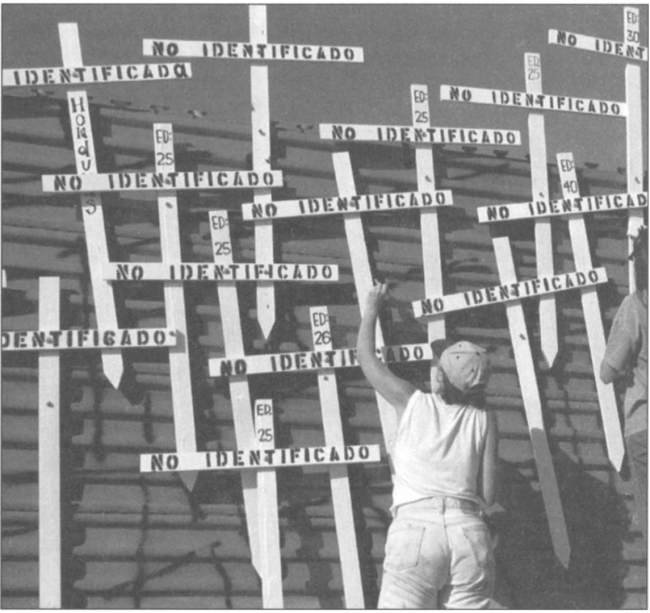

As Andreas reports, this world of relatively free movement and highly professional coyotes would change dramatically under the Clinton administration as the border became “the busiest land crossing in the world,” at once a site wide open to free trade under NAFTA but strictly closed to the free movement of labor. In short, it became a place of economic integration and social exclusion.

Andreas deftly captures the central contradictions: Unwilling to face the political blowback of the kind of amnesty Ronald Reagan had offered undocumented people in 1986, Clinton failed to develop any plan for the orderly control of migration of Mexicans and other immigrants into the United States other than one guided by the supposition that the country wouldn't require a policy on migrants if no one were to migrate from Mexico. His thinking was that this desirable outcome could be obtained simply by making all the normal high- traffic border crossings impenetrable. He would achieve this by building higher fences and “beefing up” the Border Patrol, while militarizing the border with troops from the Army and National Guard fitted out with weapons and technology from the Vietnam War—equipment for which, we might poignantly note, there seemed to be no other use in this relatively peaceful pre-9/11 period.

Click here to read the rest of this article.

To read "Borderless Economy, Barricaded Border”, click here.