Haz clic aquí para leer la versión en español.

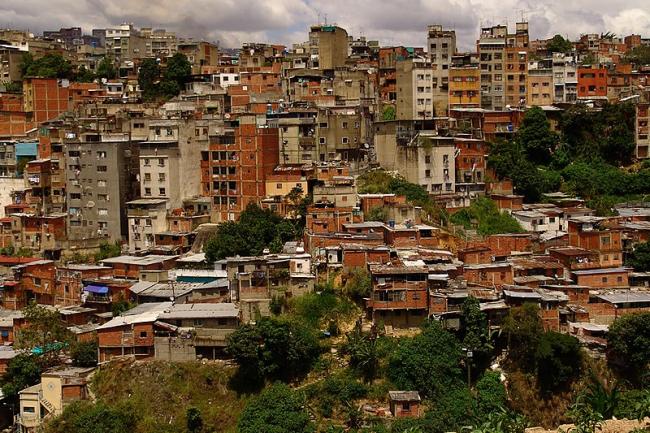

Whereas protests in past years against the government have tended to be centered in wealthier neighborhoods, in January of this year, protests against Maduro began to break out across a number of poor and working-class neighborhoods, in places like Catia, La Vega, El Valle, and Petare. At the end of that month, we began conducting research on the recent turn of events connected to these protests.

For some in the popular sectors, like previous confrontations between Chavismo and the opposition, this latest juncture is evidence that now more than ever one must stand firm against imperialism. Cristina, a single mother in her 30s who lives in the 23 de Enero neighborhood of Caracas and has supported the Bolivarian Revolution since her youth, says she has no more faith in Juan Guaidó—the current face of the opposition—than she did in Leopoldo López, leader of the hardline opposition party Voluntad Popular (Popular Unity), or Pedro Carmona, who the military appointed President during the two-day military coup in 2002. For her, they all represent a struggle to roll back the advances made by the revolution, to return power to the hands of the old guard.

However, perhaps a more general sentiment in many popular sectors is that neither “side” can be trusted; in other words, the desconfianza (distrust) that made it difficult for some to support the opposition a few years ago has contaminated Chavismo as well. This is the sentiment that we have noted while conducting preliminary research in Catia, a poor and working-class sector in west Caracas, on perceptions of the current political situation in the country. As part of this research, we organized a conversation in Catia with eight women from the neighborhood of Los Magallanes about their thoughts on Maduro’s second inauguration amid allegations of unfair electoral practices, Juan Guaidó’s proclamation as president on January 24, and what it means for the future of the country. The women live in the same neighborhood but have diverse political histories. Two of the women, whom Hanson has known for eight years, were ardent Chavistas until a few years ago. Others had been long-time opposition supporters.

Que Venga Cualquiera Que no Sea Maduro (Anyone Who Isn’t Maduro)

Venezuelans are quite equipped to “roll with the punches.” Attempted coups, violent protests, and numerous volatile elections have scarred the political landscape for almost 20 years now. For those familiar with the Venezuelan chispa, it would be unsurprising to hear that the almost two-hour long conversation we organized was filled with laughter. At the same time, however, the women we spoke with were weary, worn out by the current state of politics and unsure of whom to trust. As Yoana, a teacher in her forties, put it, “There is no one to believe in now... we want a change, but we don't know with whom.”

In 2014, the majority of people Hanson worked with felt it was safer to stick with Maduro: "Mejor el diablo que conoces que el angelito desconocido” (better the devil you know than the angel you don’t). They did not feel that the opposition would “do right” by them, and they did not feel represented by demands being made in opposition protests. Despite worsening economic conditions and their concerns about undemocratic tendencies within Chavismo, they did not support or participate in protests at that time. In contrast, increasing disappointment and distrust over the years has led to a very different conclusion now: “Que venga cualquier persona, queno sea él (Maduro)” (Anyone who isn’t Maduro).

In some ways, the women described hope for the future as a luxury only those outside of the country could afford. The women laughed at Instagram and Twitter accounts of famous Venezuelans living abroad, joking about how easy it must be to support Venezuela and believe in its future while shopping in Miami.

While some of the women agreed that Juan Guaidó could represent a short-term hope for a change in government and a means of escape from the incompetence of Maduro, they were uncertain about what might happen if a change in government actually took place. At some point during the conversation, each of the women remarked in one way or another that there is no difference between Maduro and Guaidó. While one man is fighting to maintain his position in power, the other is fighting to gain it. As one participant in the interview put it, both are engaged in a fight to distribute the spoils of war among their inner circle. Their distrust—perhaps more accurately their disgust— with current levels of corruption and cronyism has left them with little reason to believe that things will look different regardless of what happens in the coming weeks. As Yoana said, “the opposition themselves want to divide the country; this is the same opposition that just a few years ago left a trail of bodies behind them” during protests against the government.

These women’s experience with politics has led them to believe that if the Maduro government has plundered the country, many opposition leaders have abandoned it. The women brought up figures such as Antonio Ledezma, a long-time Acción Democrática (Democratic Action) politician and former mayor of Caracas, Manuel Rosales, founder of the Un Nuevo Tiempo (A New Time) party and previous governor of Zulia state, and Julio Borges, one of the founders of Primero Justicia (Justice First) and former head of the National Assembly—all of who have been charged with crimes by the Maduro government and/or barred from participating in politics. Yet after negotiating with Maduro, some said, they went on to leave the country with their families to save themselves.

Skepticism over the political process has become so saturated that some view contestation over it as a farce. During our conversation, some speculated that the government allowed people like Guaidó and Leopoldo López to montar un escándalo (put on a scandal) every few years in order to document and monitor who mobilizes against the government and who doesn’t. “Everything, all of it, is a political strategy,” said Yoana, scoffing in disgust. Indeed, the context appears similar, politically and socially, to the one from which Hugo Chávez himself emerged. There was a profound crisis of representative democracy—abstention rates soared and 85 percent of Venezuelans polled agreed that political parties did nothing to help solve the country’s problems—and over half of the population lived below the poverty line. In that moment, Chávez was able to generate excitement at the grassroots level and began to build hope around the concept of poder popular (popular power). Mobilization and support was largely dependent on Chávez’s charisma, but also his ability to make popular sectors feel represented and included through programs that provided free healthcare in poor neighborhoods, a system that sold affordable food in these areas, and free education initiatives.

The Maduro government has crushed this hope for most former Chavistas; his approval rating in January of this year had fallen to 21 percent. The women we spoke with were fed up with the current government and its discourse. They are tired of being told that there is no medicine or medical supplies, and that they do not believe it when the government tells them this is not their fault, but rather due to external intervention. They are tired of worrying about bringing their children to the local hospital because the nurses and doctors “tell us to get out of that shithole,” in the words of one woman, that their children will leave in a worse condition if they decide to stay.

The women took turns telling stories of lines to get food, to register the birth of a child, or to simply unblock a bank account. They told the story of one line so long that it wrapped around a central avenue in west Caracas. People began to stand in this line, like many others, desde la madrugada (from the break of dawn) to register legal documents. According to the women, as the day dragged on, Diosdado Cabello—the current president of the National Constituent Assembly and one of the most powerful figures in the governing PSUV party—observed the line and decided that he didn’t “like how it looked.” He shut down the registration center and re-opened it in Petare. “Who,” Chiqui, a mother in her early 30s, asked, “is going to stand all day and night in a line in Petare?” an area that is on the other side of Caracas and considered by many in Catia to be one of the most dangerous parts of the city. Whether or not this story is true, it suggests that these women feel that the current government is not only ignoring their problems, but actively trying to hide them.

If anyone has paid the price for the war that Chavistas and the opposition have been waging against each other, it is people like these women: mothers and workers with limited access to health services, food, and transportation, access that becomes increasingly limited by the month. In the current Bolivarian Revolution, these sectors have once again been exploited, excluded, and even exterminated—in 2016 state security forces killed 21,752 people, most of whom were from popular sectors.

The women worry that their suffering over the past few years has hardened them, has changed the very ways in which they relate with and connect to others. Chiqui told us: “I used to like to help people, sometimes I still do. Like with this guy I work with, he is very Chavista and he still believes in all this, but he has nothing to eat...Sometimes I think about bringing him a bit of rice, some pasta. But no, then I think, “Que coma patria!” (roughly, “let him eat his patriotism.”)

Does Guaidó Stand a Chance in Chavista Territory?

The responses we’ve heard in Catia suggest that at least some support for Guaidó comes from exhaustion, not enthusiasm. “No me causa emoción” (I’m not excited about him) was the sentiment of Katy, one young mother of three, “Why,” she asked, “do people get so excited about someone they don’t know anything about?”

However, this does not mean that Guaidó could not come to elicit enthusiastic support among places like Catia. He has elicited more support among popular sectors than other opposition leaders in the past few years, most likely due to Maduro’s unpopularity but also because, according to some, his discourse is less violent than opposition leaders before him—though this seems to be changing as the weeks drag on. He also doesn’t come with as much baggage as his predecessors, if nothing else but because much less is known about him. Facing such high levels of discontent with the Maduro government, Guaidó could be well positioned to win over these sectors, at least in the short-term.

As of yet, though, aside from his comments about abolishing the FAES—the special tactical units of the National Police that have killed hundreds of poor Venezuelans—Guaidó has remained relatively silent on policies that specifically focus on the poor and working classes. And the members of our focus group have taken note. No one was convinced that Guaidó had the interests of “el pueblo” (the people) at heart. Both Katy and Yoana wondered, “What are his intentions as president?” as others nodded in agreement. “What is he going to do for me?”

Historically, the opposition’s demands have focused on calls for democracy and new elections, not the concrete needs of those in poor and working-class neighborhoods. But protests in these areas more often than not have to do with demands for services, like water or gas, or denouncing the inconsistent arrival of CLAP bags—basic foodstuffs provided by the government that are essential for many families as the economy has deteriorated, which some opposition leaders have denounced.

Guaidó gaining a foothold somewhere like Catia, which has been a traditional stronghold of Chavismo, will require talking in specifics about how an opposition-led government would improve the living conditions of those who reside in these places. Henrique Capriles came very close to beating Hugo Chávez in 2012 precisely because he was able to win over considerable popular sector support through endorsing social programs that the Chávez government had created, arguing that they not only be maintained but improved and extended. Whether these assertions could be taken in good faith is another question.

For years the opposition coalition has asserted that it represents that majority of the country, while ignoring the majority of Venezuelans—the poor and working classes. Can the opposition offer a meaningful alternative to the cronyism, corruption, and exploitation that has marked Maduro’s government? Until they accept and start to address the doubts and concerns that exist, they will continue to exclude a large majority of the population from their policies and practices, those who inhabit the most precarious and vulnerable spaces—even while the Maduro government denies their suffering.

Long-Term Legitimacy

Regardless of who comes to power in the coming period, the government that emerges from the showdown will need to gain support among the population, and will need to rebuild trust in a context where politicization has not only torn apart political institutions, but has also ground down hope in the future. Almost 20 years after the beginning of the Bolivarian process, these women in Catia continue to remember Chávez as sparking something that has now burned out: “The first time I voted was for Chávez. My second time voting, I voted for him also. Now I don’t believe in anyone.”

Since Juan Guaidó’s claim on the presidential office on January 23 in front of tens of thousands of cheering Venezuelans, political analysts and pundits, legal scholars, and Twitter aficionados have debated the legality of Guaidó’s announcement. Indeed, depending on how the constitution is interpreted, one of the two men has a rightful claim to assume executive power. However, in the long-term, proving the constitutionality or legality of either Guiadó’s or Maduro’s claims will matter little on the ground if people view politics as an elite arena where political actors fight to secure resources for a small group of cronies. While there is much to critique about Chavismo, for a number of years it accomplished something of a miracle: belief in a political project, belief that was contingent on material but also symbolic recognition by political actors. Chávez gave the poor a central place in not only public policy but political discourse.

At some point rather than asking who has the rightful claim to authority, leaders must begin to ask how to resuscitate belief in the political project they are offering, to show that they are committed to fulfilling the political promises that the Maduro government has failed to make good on. To inspire not only hope but also confidence and trust will require that the needs of the people be put before the interests of politicians.

Rebecca Hanson is Assistant Professor in the Center for Latin American Studies and the Department of Sociology and Criminology & Law. She is currently writing a book on policing and citizen security in Venezuela, based on ethnographic and interview research she has conducted since 2012.

Francisco Sánchez is Professor at the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello in Caracas and member of REACIN (La Red de Activismo e Investigación por la Convivencia).