In recent weeks, anti-government and anti-corruption protesters have taken to the streets in Haiti. Since February 7, they have held daily marches and erected roadblocks and barricades throughout the country, all part of what some have called “Operation Lockdown.” This is not the first time Haiti has undergone debilitating protests in response to government corruption allegations and economic crisis, but the context and characteristics of today’s unrest are new in several key ways. For one, the younger generation—who grew up in the wake of the 2010 earthquake—comprises a majority of the population, and social media has begun to play a central role in anti-government mobilization. Furthermore, the protests are responding to an unprecedented fuel crisis in Haiti, fueled by the Haitian energy sector’s dependence on oil imports. While today’s protests stem from decades of economic and political crisis, the current wave—which began in July 2018—is unlike anything that Haiti has witnessed before. Today’s protests represent a larger crisis of faith, not just with the current government, but also with the neoliberal state and perhaps even democracy itself.

The Protestors’ Immediate Demands

In the immediate sense, protestors in Haiti are calling for President Jovenel Moïse to resign over corruption and graft allegations. Police repression of protests has grown increasingly violent—as of February 26, dozens of people had been killed or injured. Meanwhile, Moïse has refused to budge. In an attempt to quell the unrest, on February 16, Prime Minister Jean-Henry Céant promised a series of spending cuts to address a mounting budgetary crisis and bolster confidence in the government. There was a brief respite in the streets following Céant’s address, but marches and demonstrations have since resumed and protesters have questioned whether the current government can implement Céant’s proposed reforms, which include a promise to conclude an investigation into a corruption scandal that involves key officials from the current and previous governments.

Beyond Moïse himself, protesters are also expressing anger and exasperation over lavi chè—a Haitian Creole term referring to the high cost of living on the island. In fact, the cost of most basic goods in Haiti usually exceeds daily household budgets. The country’s poorest citizens, who live on about $2 a day, are thus forced to buy goods in fractions of units and often on credit. This means that whenever the prices of food or fuel go up, even marginally, people take to the streets. As decades of neoliberal structural reforms have caused prices to rise dramatically and wages to remain low, lavi chè has been a consistent issue in Haiti for a generation. In 2008, soaring global food prices provoked widespread demonstrations that nearly toppled the otherwise popular government of René Préval, who was president from 1996 to 2001 and again from 2006 to 2011.

In recent weeks, the cost of staples like rice, beans, and cooking oil has nearly doubled, as the country grapples with high inflation, a sinking local currency, and chronic poverty. In the streets of Port-au-Prince, protesters are calling for an end to mizè (misery), grangou (hunger), and blakawout (blackouts)—problems that they are linking to the economic policies of the government and international community and to the corruption of what some have called the “predator state.”

While demonstrators have denounced the high cost of living writ large for years, the recent wave of protests initially began last summer in response to gas price hikes after the government announced an IMF-backed plan to end subsidies on fuel. Haiti and the Caribbean already have some of the highest energy costs in the world, and previous Haitian governments have used subsidies to absorb some of those costs. Yet the new policy, signed in February 2018, would do away with these subsidies, and was set to increase the prices of gas by 38%, diesel by 47%, and kerosene by 51%. This is particularly important because Haiti imports nearly all of its energy in the form of oil and diesel (used to make electricity or power generators), with kerosene and charcoal as the most common energy source in most homes. The government temporally shelved the plan last summer, after facing anger and widespread demonstrations. But the overarching economic policy of austerity, mandated by the IMF as a condition for new loans, still holds, with the IMF now pushing for the government to end subsidies through a gradual rate adjustment. Meanwhile, economic problems in Venezuela amid a growing political crisis and intensified U.S. sanctions over the past several months have had ripple effects in the the 14 Caribbean nations whose energy sectors rely heavily on subsidized Venezuelan oil through the PetroCaribe program.

PetroCaribe and the Venezuela Connection

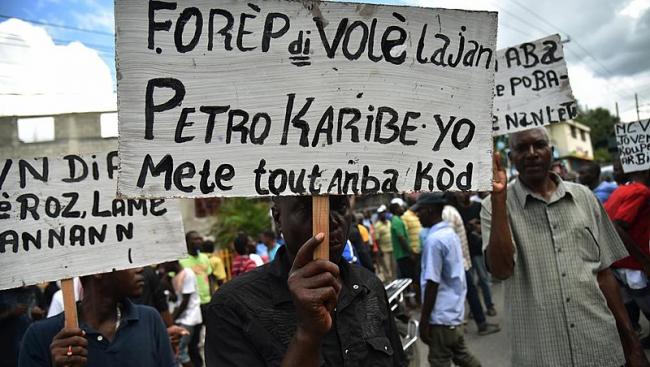

In August 2018, a tweet, sent by Haitian-Canadian filmmaker Gilbert Mirambeau Jr., asked a simple question: “Kot kòb Petwo Karibe a???” (Where is the PetroCaribe money?). He was referring to nearly $4 billion of fuel sales and development funds from the PetroCaribe program, the regional oil alliance spearheaded by Venezuela and Cuba, that have gone missing. The tweet went viral, and Haitians launched a growing new movement both online and off called the PetroCaribe Challenge—an anti-corruption campaign that has galvanized protesters and has become a key driving force in Operation Lockdown.

PetroCaribe began as a discounted oil sales program in 2005 and was initially heralded as a new way to lower fuel costs for Caribbean member states while promoting economic cooperation in the region. Haiti joined the program in 2006 when then-president René Préval signed onto the deal. Haiti’s involvement in PetroCaribe effectively ended in 2017, after the United States imposed new financial sanctions on Venezuela that, among other things, made it impossible for the Haitian government to send payments to Venezuela.

But the end of the deal exposed the fact that the government hadn’t been regularly paying its bills and had, instead, racked up $2 billion in debt. To make matters worse, a Senate report released in November 2017 claimed that $1.7 billion from the PetroCaribe development fund had been lost or stolen, and an audit released at the end of January 2019 by Haiti’s Superior Court of Accounts and Administrative Disputes confirmed those claims. Much is still unknown, but one thing is clear—the investigation into the PetroCaribe funds has so far implicated leading government figures from the ruling Haitian Tèt Kale Party (PHTK), including President Moïse himself.

For the Haitian government, the end of imports through PetroCaribe has meant the country must now buy its oil from U.S. providers, in U.S. dollars, continuing a long-standing project of U.S. energy imperialism in the Caribbean. In January of this year, a widespread fuel shortage in Haiti led to weeks of blackouts, gas shortages, and long lines and high prices at gas stations. The shortages were due to the government’s inability to pay its bills to the U.S.-based energy supplier Novum. Having exceeded their credit limit, the government was forced to pay cash-on-demand for oil imports, although it took them weeks to find the funds to do so. In the meantime, oil tankers sat idly off the coast, unable to deliver fuel. There are still widespread shortages of oil, diesel, and electricity throughout the country. The shortages, coupled with the recent demonstrations and blockades, have forced schools, businesses, and even major hospitals to close down.

A Crisis of Faith in the Neoliberal State

The PetroCaribe scandal and the high cost of living in Haiti are the two issues most directly driving the current protests, but like other emerging movements around the world, people in Haiti are mobilizing in protest of economic policies that are slowly killing them, and because governmental and global institutions have been unresponsive to their needs. The protests that have now been unfolding for almost a year are not just targeting the Moïse administration; they are also targeting the economic and political status quo in Haiti. In that sense, the protests signal a crisis of faith in electoral democracy and the neoliberal order itself. This is why the recent proposal from the government, which has focused on reduced government spending and minor reforms, is unlikely to assuage the protestors’ demands.

The current government is dependent on the international community for both its operating budget and its claim to legitimacy. The UN Core Group (the United States, Canada, France, Brazil, and representatives from the OAS) and international financial institutions like the IMF underwrite the government’s economic plan. For those international institutions, the development plan for Haiti, which relies on austerity and privatization, remains unchanged despite decades of evidence that these policies have increased inequality in the country and despite widespread popular movements against such policies. Yet given his own reliance on loans from institutions like the IMF, President Moïse has few options. Despite the recently announced economic reforms, the Haitian government can do little to change the prevailing structural relations that are causing the underlying economic and political crises in the country.

Realizing his hands are tied, Moïse has begun to shore up his political support from the international community. For example, he reversed Haiti’s decision to recognize Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro as the legitimate head of state, and last month, joined the United States and its allies in recognizing opposition leader Juan Guaidó as the country’s new leader. Moïse has also shuffled embassy staff around the world and replaced ambassadors with his own trusted allies, a likely sign that he is seeking international backing to help him remain in power. He recently sent André Apaid (a wealthy Haitian businessman and a leading figure in the 2004 ousting of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide) to meet with U.S. government officials to seek support for his government. After weeks of protests, the U.S. government said it was preparing to send humanitarian aid in response to the crisis. But critics in Haiti see this as just another example of how the international community is helping to keep a corrupt government in power. Complicating the situation, two weeks ago five heavily-armed Americans and several foreign nationals were arrested in Haiti, amid rumors that they were in the country to carry out attacks on anti-government protesters.

All of these moves have only served to deepen peoples’ sense of distrust and dissatisfaction with the government, which they see as incapable of addressing the myriad problems facing the country. Indeed, the prevailing situation in Haiti—energy dependence, debt, trade liberalization, neoliberal reforms, a weak government, low wages, and high prices—is the result of a series of programs and policies put in place by a series of governments propped up by or beholden to international institutions and hegemonic countries. The anti-government protests are thus not just targeting the Moïse government; they are also targeting a model of the Haitian state that has itself become a key factor in reproducing a structural crisis of debt and dependence from which the country cannot seem to escape.

A New Generation Responds

Many of the issues being raised now have been raised before. Yet, there is something new happening in Haiti—a growing sense that end of the Duvalier dictatorship and the long transition to democracy has not solved the country’s problems; instead, the democratic era has seen the Haitian state become weaker and more indebted to foreign powers. Now, people are rejecting a global neoliberal order that continues to make life in Haiti “unlivable,” according to anthropologist Gina Athena Ulysse. Perhaps the most potent example of this is the humanitarian aid effort launched after the 2010 earthquake. Given that more than half of the population is under the age of 25, there are millions of Haitians who have come of age during this reconstruction era, which was a resounding failure. They have seen little in the way of tangible results and they are wondering where all the money went. They have lost faith in the minimalist democracy pushed by the international community and by a series of Haitian proxy governments. For them, the democratic era has given rise to a state that actively works against the interests of the Haitian people.

For now, Haiti stands at a crossroads. It is not clear where the country is going, or what will happen next. What is clear, however, is that the recent wave of protests is unprecedented, reminiscent in size and scale of the popular movement in the 1980s that ushered in democracy and rejected decades of dictatorship. That popular movement began as a project by the Left to gain control of the state and to transform it through democratic institutions. Yet, in the ensuing decades, a repressive rightwing coalition has managed to game the system and to use extra-constitutional means and international support to masquerade as the legitimate state and to hide behind a veneer of quasi-democracy. Now, current protesters are fed up, and connecting their frustration not only with Moïse’s government, but with the entire model of the neoliberal democratic state, which has turned the Haitian state into little more than a hollow shell, a broker that pushes IMF-backed economic policies and channels massive amounts of development assistance and humanitarian aid into private pockets. Democracy was once heralded as the solution to the problem of dictatorship; now, an increasing number see democracy, neoliberalism, and humanitarian intervention as the primary obstacles towards ending the crisis. The conjuncture has led some to wonder: after democracy, what comes next in Haiti?

Greg Beckett is assistant professor of Anthropology at Western University. His book, There Is No More Haiti: Between Life and Death in Port-au-Prince, has just been released by the University of California Press.