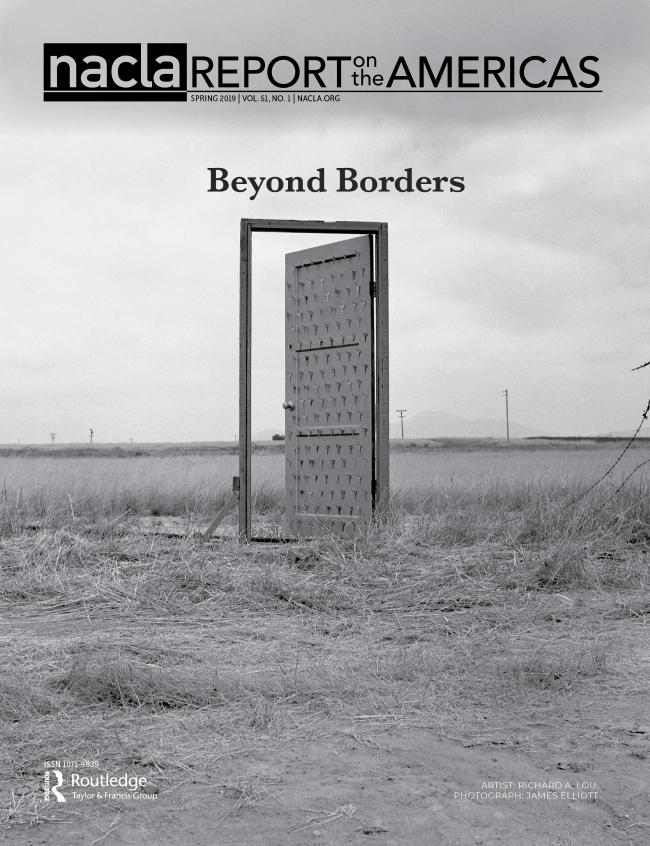

In May 1988, Chicano border artist Richard Lou walked across the U.S.-Mexico border to Tijuana, where he’d grown up. He held in tow a free-standing, workable door, which he then fixed on the border. At the time, there was some chain-link fencing, much of it in very poor shape, along the border, but only in the most urbanized stretches, and there were no walls as we see today. That changed just a few years later, in 1990, when U.S. authorities constructed several miles of steel wall along the international boundary in the San Diego area, where the majority of unsanctioned border crossings were taking place at the time.

Yet the vision of the door, standing still in the desert sun, evokes a sense of the arbitrary lines that cleave nations, environments, and people from one another. The symbolism of Lou’s project went a step further. The artist wandered the streets of Tijuana with 250 keys, which he gave to residents of La Colonia Roma and Altamira so they could use the door, moving from one nation-state to another. As Latinx feminist art historian Guisela Maria Latorre has written, Lou’s political work “questions the very existence of this border and the extreme inequities that it has ushered in, yet it underscores and celebrates the cultural hybridity that emanates from it.”

An issue about borders couldn’t be more timely, when the Trump administration has posed the U.S.-Mexico border and the people who cross it as the central threat to U.S. Americanism. Yet this focus displaces the longer-term history of violent border exclusion across the Americas— the brutality, inequality, and cultural hybridity they embody, as Latorre suggests—in various conceptions

That’s why this issue focuses on a variety of borders across the Americas, literal and symbolic. In fact, our back cover depicts the Muro de la Vergüenza, or the Wall of Shame, in Lima, Peru, which divides the wealthy Casuarinas neighborhood from an informal housing development long neglected by the Peruvian government. As Leigh Campoamor writes in the issue, this internal border embodies both the physical inequities borders draw, as well as the way borders serve to separate people, differentiating them, whether by nationality, ethnicity, class, or socioeconomic status. These mirror the less literal but just as real walls that privilege the flow of commerce over the flow of people, that give the wealthy the right to move while caging in the poor.

To read the rest of this article and content from this issue, click here.