To read a Spanish-language translation of this story, click here.

At dawn on March 14—celebrated internationally as the Day of Action against Dams and in Defense of Rivers—Afro-Mexican, Indigenous, and mestizo peoples met on the shores of the Río Verde to participate in a ritual of gratitude and resistance.

They were gathered for the Río Verde Festival, organized each March by the Consejo de Pueblos Unidos en Defensa del Río Verde (Council of Peoples United in Defense of the Río Verde, COPUDEVER). This water protector movement was formed in 2007 when dozens of communities organized to stop the Federal Electricity Commission from building a hydroelectric dam on their river, which they say would flood their homes and contaminate their only source of water.

The Río Verde—known as Stäitya Taná in Chatino and Yutya Cuy in Mixtec—is the main source of life for dozens of farming and fishing towns in the Southern Sierra and Pacific Coast of Oaxaca. “The Río Verde is part of us; or rather, we’re part of that nature, of all that surrounds us,” says Eva Castellanos, a COPUDEVER member from the community of Paso de la Reyna. “If the river didn’t exist, Paso de la Reyna definitely would not exist.”

After 12 years of marches, blockades, and assemblies, not a single rock has been laid for the foundation of the megaproject. Today, COPUDEVER is confronting a new challenge: to transform its successful opposition of the dam into a multi-generational movement in defense of the river.

For towns like Paso de la Reyna this has meant rewriting local laws to ban extractive projects and exert more control over the land and water. Residents are also redefining their identity as Indigenous water protectors by restoring ancestral traditions and creating new ones. One key to this metamorphosis has been the Río Verde Festival, an autonomous holiday that brings communities and allies together to give thanks for their natural commons.

El Río Verde: Collective Social Property

The smell of conga—a freshwater crab found in the deep parts of the Río Verde—is enough to rouse the overheated travelers who have come for the Río Verde festival from their late-afternoon daze. They take seats in the communal kitchen of Paso de la Reyna, where women in floral dresses tend to the fire and listen to tropical cumbia. Over the loudspeaker, a voice asks neighbors to donate tortillas for the event. A committee of men swiftly replaces each empty plate with a fresh pile of gleaming, juicy conga.

Paso’s high level of collective organization is a legacy of not only the community’s sustained resistance movement but also its Indigenous, agrarian roots. Paso was founded as an ejido—a form of communal property—for Chatino farmers during the 20th-century land reforms that followed the Mexican Revolution. While in recent decades the Mexican government—pushed by international institutions like the World Bank—has privatized much of this land, the area surrounding the Paso de la Reina Hydroelectric Project has resisted this tendency. It’s still 95% percent communal property.

This territory also supplies water for a large segment of Oaxaca’s population. The Verde-Atoyac River Basin, where the hydroelectric project would be located, covers 20% of the state’s surface area, home to over a third of its residents. The basin maintains nearly 15% of Oaxaca’s existing mangrove area. The Río Verde is considered one of Mexico’s 51 most important rivers, through which 87% of the country's surface water runoff flows, according to a report from the University of Campeche and the Institute of Ecology, Fisheries and Oceanography of the Gulf of Mexico. In the case of the Río Verde, its runoff plays an essential role in replenishing the Pacific watershed.

Yet elders from Paso say the river is today just a shadow of its former self. Manuel Sánchez—a 75-year old Paseño whose Chatino grandparents were among the first settlers in the community—recalls a riverbed filled with diverse flora and fauna, each of which played a vital role in the ecosystem.

Back in those days, Paseños were always prepared when the river flooded, he explains. That’s because the coastal “chameleon” toad issued a timely warning: “Those little animals started to scream and scream and scream!” recalls Sánchez; “That signaled the river was going to overflow… You didn’t sleep, helping your neighbor so that he wouldn’t lose anything. And nothing was lost.”

But in recent decades, deforestation and drought have led to the toad’s extinction: “It’s been years since I’ve seen those animals,” says Sánchez, who adds that crustaceans and fish have also vanished due to changes in the riverbed. Sánchez recalls that when he was a child, his father would go fishing at night with a dozen neighbors. By sunrise, they would return with enough shrimp and diverse species of fish to feed each family for the entire week. But this came to an end in 1992, when Mexico’s Water Commission built the Ricardo Flores Mágon dam downriver, which residents say has impeded the natural migration of many species. “Now all we have left is shrimp and mojarra,” says Sánchez.

The memory of this loss helped to spur a broad resistance movement that began in 2006, when affected communities discovered plans for the new dam from the local newspaper. Jaime Jiménez Ruiz, a COPUDEVER member and law enforcement officer from Paso de la Reyna, says that not only were residents not properly informed about the project, they were also never consulted as required by Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization, of which Mexico is a signatory.

The Council of Peoples United in Defense of the Río Verde

Struggles to prevent the damming of rivers are also social movements against disappearance. In Mexico, from 1936 to 2006, the construction of over 4,000 dams led to the displacement of approximately 185,000 people from their communities. Human rights organizations say that in the past 10 years alone, the construction of dams in the country has been associated with the detention of over 250 people and the assassination of at least eight water protectors.

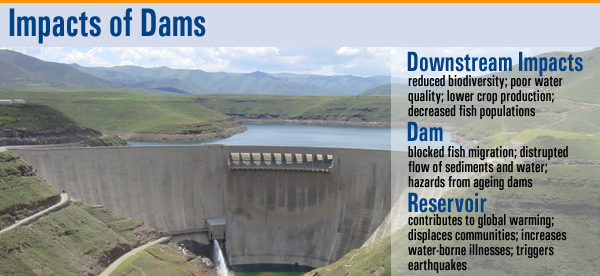

The anti-dam movement is also a struggle against the disappearance of a whole ecosystem, made up of myriad forms of life that depend on a river’s flow of nutrients and sediment. According to a report from International Rivers, large-scale dams can harm their environments by blocking fish migration, changing the river’s temperature and chemical composition, trapping sediments that are necessary for downstream habitats, and causing the buildup of contaminants. “Even subtle changes in the quantity and timing of water flows impact aquatic and riparian life,” the report states. This can “unravel the ecological web of a river system.”

On the coast of Oaxaca, the nonprofit organization Servicios para una Educación Alternativa (Services for an Alternative Education, EDUCA, where I am currently employed) has calculated that the Paso de la Reina Hydroelectric Project would directly affect 17,000 people and over 7,400 acres of land, and cost $1.1 billion USD. The project would consist of two dams—one upriver of Paso measuring 147 meters, and a second, 20-meter dam located downriver from the town. “Practically, we were going to end up like the ham in the middle of the sandwich,” says Jiménez Ruiz, the COPUDEVER member.

In 2009, when Electricity Commission workers entered the proposed dam site escorted by state police, community members agreed it was time to act. “With the little experience we had, we decided to establish a blockade,” says Jiménez Ruiz. For eight years, the men and women of Paso maintained a 24-hour security encampment at the entrance to the community, impeding the access of workers, machinery and security forces associated with the hydroelectric project. While community members decided to scale down the blockade in 2017, they maintain active security at all of town’s entrances and exits.

For COPUDEVER, the blockade was just one part of a multi-pronged strategy to prevent the megaproject. Members have worked with religious and civil society groups in the region to mobilize neighboring communities and organize mass marches. Beyond Oaxaca, COPUDEVER’s participation in the Movimiento Mexicano de Afectados por las Presas y en Defensa de los Ríos (Mexican Movement of Peoples Affected by Dams and in Defense of Rivers, MAPDER), and the Red Latinoamericana contra Represas y por los Ríos (Latin American Network against Dams, REDLAR), has enabled water protectors to coordinate strategies and actions with communities across the continent.

Since 2016, several COPUDEVER communities have shifted their focus to strengthening community control of natural resources. In the local laws passed by Paso de la Reyna last year, residents not only managed to prohibit large-scale extractive and energy projects like hydroelectric dams, metallic mines and pipelines, they also approved regulations to remedy the over-exploitation of the Río Verde’s resources.

The goal was “to find a proposal for managing our communal lands and natural resources equitably,” explains Jiménez Ruiz, the law enforcement officer who also played a key role in writing the new ordinance. In practice, this has meant banning the sale of the river’s resources outside of their community, as well as placing limits on their own consumption of conga, fish, iguana, deer, and wild boar, depending on these animals’ breeding seasons and the health of their populations.

To accomplish this, it was important to get everyone on board—including proponents of the dam who had stopped engaging in community life for nearly a decade. “There was a deterioration in our town, the town was torn to pieces,” explains Jiménez Ruiz. For eight years, one sector of the community stopped participating in collective work (known as tequio in Spanish), and also opted out of the town’s “cargo” (charge) system, through which residents are assigned political, administrative, and security tasks in the local government. “It was necessary for these people who withdrew to return,” says Jiménez Ruiz. In the end, this is precisely what happened. “Right now Paso’s vision is different than it was last year.”

Festivity and Autonomy

The struggle of recent years has not only strengthened the community’s control over natural resources, but is has also helped to revitalize their culture as native water protectors. “After so much exhaustion and running all over the place, fighting with governments, we also need to recognize this and join together in celebration,” reflects Jimenéz Ruiz. “Just as sometimes there is pain, there is also joy.”

The community celebration, fundamental to cultural identity, not only brings residents together to celebrate what is sacred; it also requires collaboration in numerous tasks, from the preparation of food to the decoration of devotional altars. In turn, the celebration revitalizes collective commitment through conviviality and ritual. “It’s an articulating axis of collective work,” explains Astrid Paola Chavelas, a postdoctoral student in Rural Development and member of the Red de Defensoras y Defensores Comunitarios de los Pueblos de Oaxaca (Network of Community Defenders of Oaxaca, REDECOM).

The men and women of Paso don’t think twice about staying up all night to celebrate their river, then driving to a remote village to speak about their water protector movement, then traveling back all night—all while standing in the back of an open-air pickup truck. Festivity is part of Paseño resilience.

Spirituality is also a key facet of the festivity. Indeed, long before the dancing started, community members inaugurated the celebration on the shores of the Río Verde at dawn through rituals of gratitude rooted in Chatino, Maya, Mixe, and Mixtec cultures. They followed these traditional rituals with new practices like the floral ceremony, in which Paseños spread flowers along the riverbed to honor its natural abundance as well as express the community’s aspiration to restore it.

The communities’ spiritual connection with water is also apparent in quotidian practices like fishing, farming, and cooking, which have been passed down from generation to generation. These were on display throughout the humid afternoon: to bait the blanquilla fish, a handful of corn dough is placed inside an overturned clay vessel. To prepare stone soup, a river stone is heated on the fire until it is red hot, then dropped into a pot of shrimp until it boils. And to transform native maize into a feast, the possibilities are abundant: coconut tostadas, empanadas, a corn flour drink called atole, and sweet squash and bean tamales.

Many of these cultural practices are tied to the communities’ Indigenous identity, which they have readopted in recent years. In fact, last year was the first time that Paso’s laws identified the community as native Chatino. “We described ourselves as an Indigenous people because our ancestors were Indigenous,” said Jiménez Ruiz, and because “we still preserve many ancestral customs in the town.” This includes the production of a wide variety of native corn for self-consumption, such as “olotillo, tehuacanero, rabbit corn, and black corn.”

In the past, Paseños did not identify as Indigenous due to the loss of their native language as a result of migration and a discriminatory state education system. But residents’ reevaluation of what it means to be Indigenous—along with an analysis of their cultural and political orientation—has led them to embrace this identity.

Community members are trying to build on this tradition by taking steps toward food sovereignty, starting with the prohibition of genetically modified corn and a commitment to pass native varieties of maize onto their children and grandchildren. In the end, Paseños’ goal is for future generations to enjoy the full abundance of the Río Verde. “We have to give life to our land and to our people, to ensure our children's well-being,” said Pedro González Robles, President of Paso de la Reyna’s autonomous security council, as the festival drew to a close. “Because if we falter, the government is going to enter, plunder and destroy... But by uniting we become stronger—unity is the greatest force for achieving our aims.”

Check out the following song, "Cuidemos el Medio Ambiente," written by a member of the resistance movement's Afro-Mexican communities and performed during the Green River Festival this year:

Samantha Demby writes about extractive projects, land defense, and traditional ecological knowledge in the Americas. This piece was written as part of her work on the communications team at EDUCA, a non-profit organization based in Oaxaca, Mexico.