NACLA is launching a summer fundraising campaign. Click here to show your support.

This interview was originally conducted in Spanish. Haz clic aquí para leer la versión en español.

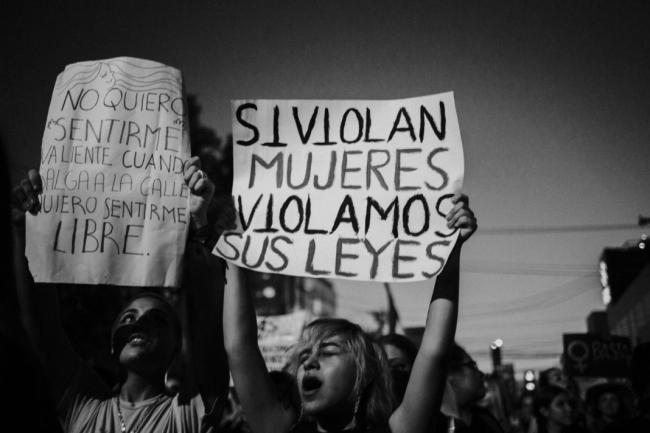

Women in Mexico protesting the alleged rape of a 17-year-old by four police officers and authorities’ inaction in the face of rampant gender violence have begun to call out another cog in patriarchal machine fueling their outrage: mainstream media coverage that routinely silences their demands while vilifying the feminist movement.

In a statement titled “Our protest is not violence” published August 17, a newly-formed collective called Mujeres+Mujeres criticized recent coverage for giving more attention to material damages sustained in the protests than to the abuses that sparked the marches in the first place. The collective also urged media outlets to improve their coverage by adopting a “gender perspective” in their reporting.

“The protests seek to reclaim the ultimate purpose of our public institutions: to impart justice,” the statement reads. “Media have a clear responsibility to help break the normalization and silence that surrounds conditions of violence women face in our country.”

Protests under the banner “They don’t take care of us, they rape us” kicked off earlier this month in response to two cases of police allegedly raping underage girls in Mexico City. In one of the cases, a 17-year-old accused four police officers of abducting and raping her on August 3. The abuse by law enforcement officers stung particularly deeply in a country where killings of women statistically are likely to go unpunished, and where several states and municipalities have declared gender alerts in recent years over crisis levels of gendered violence and femicide.

Demonstrators marched in the capital on August 12 and clamored for a meeting with the city’s district attorney. Some protesters smashed the glass doors of the district attorney’s office and hurled vibrant pink and blue glitter inside, scrawling the words “justice” and “not one more” with it on the floor. Others doused the city’s security chief in pink glitter.

The glitter and broken glass quickly became the focal point of media coverage and other responses to the march. Mexico City mayor Claudia Sheinbaum dubbed the acts a “provocation.” The district attorney, who did not answer activists’ call for a meeting, announced an investigation into the vandalism, sparking sharp criticism that authorities seemed more willing to probe and punish those responsible for graffiti and shattered windows than the perpetrators of rape.

Fueled by authorities’ dismissiveness, another march hit the streets on August 16. Once again, media coverage framed the protest as violent and vandalizing, honing in on graffiti splashed across the Angel of Independence monument, as well as an incident of a man punching a male reporter. Women’s voices remained absent.

NACLA spoke to a Mujeres+Mujeres spokesperson, who asked for responses to be in the name of the collective, about the call for an end to media coverage that normalizes rape culture in favor of more thorough, responsible, and non-discriminatory reporting.

NACLA: Let’s start with what most of the coverage of these protests did not give attention to. Most headlines focused on material damages, but not on the events that provoked the march. Why did women protest?

Mujeres+Mujeres: A big part of the anger that arose after the march and the coverage of the march on Friday [August 16] is because it reproduced almost exactly what motivated the march. Initially there was a protest against the rape of a minor on August 3 by four police officers. A group of women demonstrated in front of the district attorney’s office in Mexico City, and some threw glitter at people with the district attorney. The next day, the news in the media was about just that: the glitter. So it seemed that the fact that some women had thrown glitter was more important and meaningful and in some way more of an affront to society than the fact that a girl had been raped.

When that happened, the march [on August 16] was organized, and the surprise and frustration came about because the next day, the news once again focused on everything but what was important. What’s important is that there is systematic abuse of women in this country from economic to physical as well as many other types of violence, and these don’t get coverage, they don’t get a voice. And what the majority of headlines did address was the vandalism and the incident of violence against a male reporter committed by a man. This outrages women and the feminist community because once again, the problems and injustices that women face are not reflected.

In fact, an organization called Data Pop reviewed the media coverage from August 3, which is when police raped the 17-year-old, to August 20, and they found that on average, there were seven news articles every day in national media outlets on the topic of rape. In contrast, from the day of the march to [August 20], there were 50 news articles on average about the Angel of Independence monument and vandalism. So we’re talking about seven times more importance given to material concerns than to women’s issues. And that is somewhere that we are not willing to tolerate. That’s why Mujeres+Mujeres emerged as a call for deeper coverage and more accurate representation of the feminist movement in the media.

NACLA: When and with who did Mujeres+Mujeres form?

Mujeres+Mujeres: Literally on August 17. Those of us who now makeup Mujeres+Mujeres are women, activists, academics, journalists, and citizens who already participate or have participated actively around issues of gender, violence, reproductive rights, human rights, media, and journalism. Some of us are journalists, some of us are activists, other people are in the public sector, but we are all linked to women’s issues. And when the coverage came out on Saturday [August 17], we got together to comment on it, and it was very natural and very necessary for us to make a public statement that this kind of media coverage cannot continue.

NACLA: In the statement the collective published, you called on the media to disrupt the normalization of gender violence and to give voice to women using a gender perspective in their reporting. What does it mean to report with a gender perspective?

Mujeres+Mujeres: Fortunately, there are mechanisms and tools some media are using and recommendations from other organizations about how to produce coverage with a gender perspective. For that reason it is relatively simple for media to apply it. The difficult part is that it implies a structural change in how media define and represent themselves.

What we mean by gender perspective has to do with defining protocols for reporting explicitly that takes the needs, perspectives, and presence of women into account. It involves training reporters—women and men—and editors on gender issues. It involves being committed to giving a voice to women who live with and protest violence, without blaming them or questioning their actions. At the same time, it also involves going out to find topics, because currently the majority of news stories published on matters of violence against women are stories that the media receive, whether from the police or some kind of press release, but there needs to be an active search for this information.

On the other hand, it also involves reporting all kinds of violence that women experience, beyond physical and sexual violence. Economic violence is one of the most common forms. National media rarely touch on political violence. It also involves questioning authorities on their actions to decrease rates of violence and crimes against women. Because media almost always report on the marches, but there isn’t a sense of media seeking accountability from authorities, and that also needs to happen.

And finally, not disclosing the personal information or appearance of women who have been violated, which is what happened in the case of the 17-year-old who four police officers allegedly raped. The Mexico City government released her personal information, and the media published it. There must be clear lines for media to say they will not continue normalizing this situation and will question how and why the information is being shared.

NACLA: One typical characteristic of mainstream coverage of gender violence is that it blames women themselves for the violence they suffer. Do you see the coverage of these recent protests as an extension of this tendency, accusing women of being violent when they express their rage in the face of cases of violence against women?

Mujeres+Mujeres: Definitely. And not just that. The media representation was as if women’s outrage was irrational. It is so important to reiterate that women are angry for clear reasons. We are not irrational, nor are we overly emotional. Our outrage is well documented in the atrocities that women endure daily. We are talking about a country where seven in 10 women have experienced harassment. And of course this makes us angry, and of course when there is no response to grievances made through legal avenues, then through peaceful means, then through many demonstrations and formal petitions, you have to look for alternatives.

This isn’t to say that we’re justifying the violence committed by women by any means. But yes, we have to say that certain expressions of anger, like graffiti, are very valid when they are being ignored by authorities. Also, this isn’t a singular case for women. Graffiti and so on are historical examples of demonstrations seeking an expansion of freedom of expression and human rights demands.

NACLA: You already mentioned the fact that violence is often understood with a narrow definition and that it is important to recognize structural and symbolic violence as well. Do you consider this kind of media coverage as another form of violence against women?

Mujeres+Mujeres: More like a a mechanism that perpetuates violence against women. There is plenty of distorted coverage of women. When women are sexually objectified, or when they are blamed for the violence they suffer, this is of course a reproduction of the very violence they already experience. But it is also a way of perpetuating that violence because it does not explain why women face violence and because women often end up being victim-blamed in media coverage.

Take for example headlines like “Woman killed for infidelity.” It’s as if the woman provoked the violence against herself. This kind of framing must end because instances of violence against women will not be addressed in this way. If the media, which shapes most public opinion in society, share the prejudice and the idea that women are responsible for the violence they suffer, then they are perpetuating the conditions that give rise to that violence.

NACLA: When media incorporate gender perspective in a comprehensive way, does this perspective also go beyond providing adequate coverage of issues normally considered women’s issues, like femicide and gender violence? How can gender perspective also function cross-sectionally across all kinds of coverage to give visibility to women, especially marginalized women, in the context of a range of issues such as migration, corruption, the environment, and so on?

Mujeres+Mujeres: Of course. The media have so much information within reach to be able to explain the situations women experience, which as you say doesn’t necessarily have to be related to physical violence, femicide, and so on. In part, this is an issue with the very composition of media today—who’s in charge, who does the reporting, and the variety of topics they can cover. On one hand, it’s about highlighting the spaces where women are lacking, and on the other, exposing the typical reasons as to why women aren’t in those spaces.

Here’s an example. Oxfam Mexico just released an excellent study called “Because of my race I’ll talk about inequality” where they prove through statistical and mathematical models that women of all socioeconomic standings, races, skin tones, and income levels are more likely to face discrimination, lower income, and so on. This kind of information undoubtedly reaches media outlets, so they need to create space for it. Women’s experiences are relevant for society as a whole.

And a gender perspective doesn’t mean only talking about women’s situations. There are topics from a gender perspective that affect men and that affect people who do not identify when one of the two traditional binary genders. These topics also need to start to permeate media because they [gender non-conforming folks] are underepresented on a daily basis.

NACLA: What has been the response to the statement “Our protest is not violence”? Have any media or journalists responded?

Mujeres+Mujeres: Yes. First, more collectives and more individual women joined us. And in response to what we published, six media outlets have contacted us and interviewed Mujeres+Mujeres spokespersons, and three of those outlets have asked for some kind of course or discussion about how they can incorporate a gender perspective in their daily operations, which we’re really pleased about.

It’s not enough for us to put out a statement. Our idea is to open ourselves up to media so that we can cooperate in some way to make these tools more accessible.

NACLA: Obviously the collective is very new, but what will the next steps be to keep exposing machista discourses and challenging media to integrate a gender perspective?

Mujeres+Mujeres: We see three priorities. One, to keep highlighting the problems with media coverage. Two, to keep linking up with more women and more collectives that are interested in the issue and with whom we can develop a working group of interested parties. Three, to think about how we can cooperate with the media to start resolving this situation through workshops, for example. We’re exploring. We’re very new. The idea is to take advantage of existing knowledge and practices, and make ourselves available to the media for collaboration.

NACLA: Members of the collective are also part of the feminist movement that has participates in these protests, and the protests themselves have been met with a non-response from authorities. What are the demands of the movement now? Is it now about more than the specific cases of the young women raped by police?

Mujeres+Mujeres: For the feminist movement in general, yes, it has always been broader than that. But the reason why this case became particularly relevant and why it galvanized the entire country so quickly is because it has to do with an act perpetrated by the very authorities who are meant to protect us. That fuels the outrage. The fact that the person that should be investigating crimes against women is the perpetrator, it’s the peak of absurdity. And it is very discouraging because of course we as women are waiting for authorities to respond, yet what we actually find is that they continuously rape us, and that causes a huge gap in trust about what might happen when we take our grievances through traditional channels. And this is a reality that must be addressed.

And in Mujeres+Mujeres, we are trying to focus a lot on how we can help make the media improve their representation of women. As long as more of the community knows and understands what problems women face and what our demands are, it starts to put a lot more pressure on authorities to fix them. Authorities definitely have a debt to to women in the country. Authorities owe us attention, they owe us action, they owe us justice. That’s a demand that’s not going to stop.