Amid dismal news from Honduras of ongoing human rights crisis and high-level drug trafficking conspiracies, on August 9, a rare bright spot cropped up: political prisoners Edwin Espinal and Raúl Álvarez, jailed in pretrial detention in a maximum security, military-run prison for the past year and a half, were released on bail pending trial.

In January 2018, as protests against the deeply questioned reelection of President Juan Orlando Hernández rumbled across the country, authorities accused Espinal, a seasoned resistance activist, and Álvarez, a former police officer-turned-protester, of vandalizing the Marriott Hotel in Tegucigalpa during a large march. Both maintain authorities framed them. A social media smear campaign singled out Espinal days before police arrested him on January 19, 2018, on the eve of a national strike against electoral fraud. The focus on broken windows and burned lobby furniture at the hotel, steering attention away from the harsh and militarized crackdown on thousands of protesters that day, mirrored the government and corporate media’s broader framing of opposition protests throughout the post-election crisis.

Espinal was a vocal critic of the 2009 U.S.-backed coup whose involvement in the resistance movement became well-known after his girlfriend Wendy Avila died of teargas exposure during a protest three months after Manuel Zelaya’s ouster. Since then, he has supported diverse social struggles across the country, including working alongside assassinated Indigenous activist Berta Cáceres. Espinal has repeatedly suffered harassment and persecution as a result of his activism. Police abducted and tortured Espinal in 2010 and raided his home in 2013 ahead of the presidential election that first brought Hernández to power in a vote the opposition decried as fraudulent. Authorities have also detained Espinal on other occasions.

Espinal goes to trial for three charges related to property damage in May 2020, and in the meantime he is required to sign before a judge every week.

NACLA spoke to Espinal and his longtime partner, Karen Spring, the Honduras-based coordinator of the Honduras Solidarity Network, about the plight of Honduran political prisoners, current electoral reform negotiations, and the political outlook for the Honduran resistance.

NACLA: Obviously your release is the just outcome after an arbitrary detention, but it is still remarkable given the precedent of disregard for the law in Honduras. Is this a sign of cracks in the JOH regime?

Edwin Espinal: This is what we assume. We didn’t expect them to give us these medidas cautelares (precautionary measures) to be able to face trial out of prison. From the beginning, they had denied us due process, and all of the appeals we have filed in our defense have been denied. So it surprised us, and we came to the conclusion that the regime is losing strength. But we can’t forget that the work Karen has done [organizing for freedom for political prisoners] has been incredible.

NACLA: What was your reaction when you heard the announcement of release on bail pending trial? Did it come as a surprise or were there already hints in that direction as pressure mounted with the hunger strike?

Karen Spring: To a certain degree, I think the magistrates were acting independently, but for me, I would say that the decision was probably more political than judicial. I say that because right now Honduras is negotiating new electoral reforms. When the government was involved in a dialogue with the opposition last year from August until December, the issues on the table were electoral reforms, release and amnesty for political prisoners, human rights standards, and so on. That dialogue process failed, but for me that indicated that the release of political prisoners was very much tied up into negotiations around electoral reforms.

So when Edwin was released on August 9, a lot of people thought he was going to be released, and I was hopeful, but I kept my expectations low. He was released on Friday, and electoral reforms negotiations started in Congress the following Monday. For me it was very much a political decision, though I think there was a slight judicial decision as well.

When I found out about the news I was in the court hearing. I didn’t believe it. I said I wouldn’t believe it until he was physically standing in my house. I still kind of don’t believe it, even though he’s been out for more than two weeks. I feel like I just walked out of a war that lasted 19 months, and it hasn’t set in yet that life is kind of going back to what it was 19 months ago.

EE: When we got the news, we were in very difficult and precarious conditions. We were facing death threats, and the authorities in the prison were on top of us because we were still on a hunger strike. The director himself came to give us the news. We had another compañero with us, Rommel Herrera, and so we had a lot of conflicting emotions because it meant we had to leave him behind, alone. When he heard the news, he got very sad and almost cried. For us, we had mixed feelings. We didn’t show our happiness because we knew it was hard for him, due to the situation we were experiencing. We had to go on hunger strike to distance ourselves from the [criminal] structures that control the prison population, which had repeatedly threatened us for different reasons. We had to take that action to achieve some level of security.

NACLA: How many times did you go on hunger strike?

EE: We went on hunger strike for the first time two months after arriving at the jail. We did so because there was no water in the prison, and there was also an epidemic with many people sick with fever, diarrhea, and flu and no medical attention. We—Raul Alvarez and I—thought that if we were going to die, we may as well die fighting for our rights. We launched our first hunger strike, and we only lasted four days, because without water and without medical attention it was very difficult. But we achieved our objectives, because they had to provide us with water immediately on the condition that we would end the hunger strike. We also demanded a visit by a medical brigade to the 170 prisoners where we were.

Many prisoners thanked us, and showed us respect. But as a result of that hunger strike, we also received death threats, because organized crime structures in the prison did not agree with our action, because it challenged their leadership within the population. They told us that their way of resolving problems was to hang 10 prisoners so the authorities would respond to them. This was very psychologically and emotionally challenging for us to be told this soon after arriving.

The second hunger strike was five days before leaving the prison because for one month, we had been in a punishment cell without air circulation, without a toilet, without water. We spent a month there, and we couldn’t take it anymore. We saw the need to carry out a hunger strike. We achieved our objectives because they took us out of that cell, and on the fifth day we got the good news that they had granted us the medidas cautelares to be able to face trial in freedom. We had been put in the punishment cell because we had repeatedly reported to the authorities that we were receiving death threats.

NACLA: Why were you the target of threats?

EE: There were protests in Honduras when the government threatened to privatize health and education. Teachers and doctors organized a social struggle against the privatization plan with protests nearly every day for more than a month. There were many highway blockades, and traffic and public transport stopped, and so authorities cancelled the visitation days at the prison, or sometimes relatives of the prisoners weren’t able to get to the prison. Prisoners’ medical visits to public hospitals were also getting cancelled due to the protests. In the prison, many started to associate the protests with us, because we are part of the opposition. They started to conspire against us. They don’t care about the protests, which is logical, because if they have long sentences, they don’t care what happens outside the prison. We started to receive direct and indirect threats, and we saw indications that they were going to organize a mutiny within the prison module. That’s when we realized it was urgent for us to get out. Authorities ignored us.

Later, a new criminal code was introduced, and the prisoners were very happy, because they were going to benefit from it. The opposition was in the streets demanding that the health and education privatization reforms be overturned, but when that news got to the prison, it was distorted, and the prisoners heard that the opposition was also trying to block the implementation of the criminal code reforms—something that had made prisoners very happy. This complicated our situation. We felt they were speeding up their plans to do us harm as a way of stopping the protests in the streets. They started sharpening their knives. The organized crime kingpins had a list of the people who they were going to make pay. We were told we were on the list.

NACLA: U.S. court documents recently gave credence to what protesters decrying the Honduran “narco-state” have suspected or known for a long time: Juan Orlando Hernández is implicated in drug trafficking. This adds to a string of high-level officials being implicated in drug trafficking, including the security secretary, the chief of police, as well as the president’s own brother. But now there’s evidence the drug money reaches all the way to JOH himself and benefited his electoral campaign. Does this create a new opportunities for the resistance to increase pressure on the president?

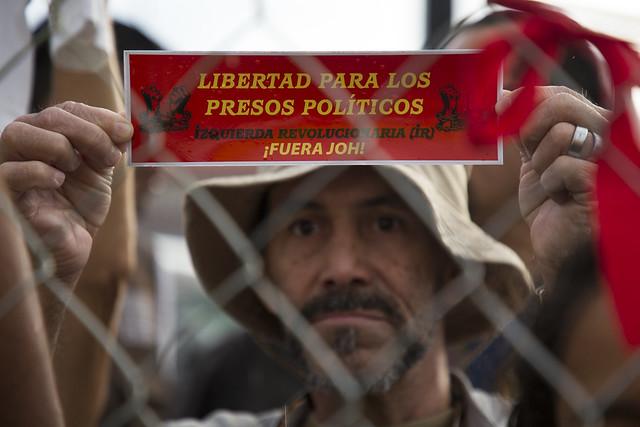

KS: The resistance and the social movements are taking full advantage of the information coming from the New York Southern District court to keep justifying ongoing protests to demand “Fuera JOH.” But at the same time, Honduran movements, social organizations, and society in general have been talking about the narco-mafia government for years, so in many ways they already knew this. Granted, the court documents are providing proof.

It is also a reminder of how the U.S. government is who is going to make the decision [about Hernández’ fate] at the end of the day. You didn’t believe us when we said it, but when the gringos say it, well then it must be true. It’s that reminder that ultimately it will be the U.S. “go ahead” that will take Juan Orlando Hernández out of power.

EE: The government is in a very difficult position. The regime of Juan Orlando Hernández is weakening every day as more proof comes out about the direct links between him and his family to drug trafficking. This gives us hope, and that hope is the fuel that moves us to keep standing up to fight and to demand the end of this regime and to begin to create new processes that will help us build a more just and equitable society.

NACLA: Shortly after the revelations about JOH’s drug money ties, the president traveled to Washington and boasted what he claimed was a strong track record on fighting organized crime and drug trafficking. The Trump administration and OAS secretary Luis Almagro, who condemned JOH’s 2017 reelection as flawed, have stayed silent. The hypocrisy from all sides is staggering. Obviously US intervention has played a big role in Honduras. At this point, how determinant is the United States and its foreign policy in what happens next in Honduras?

EE: It’s really fundamental. It’s evident that the United States is giving oxygen to this dictatorship which, as we say, is en alas de cucaracha—it’s scrambling, it’s in a very difficult situation. But the government of Donald Trump keeps propping up and supporting Hernández, and the OAS is also endorsing the government despite knowledge of Juan Orlando Hernández’s direct links to drug trafficking. It’s unfortunate because we know what this means for us as the people of Honduras. Very tough times are coming, because when regimes like this face difficult situations they start to persecute and repress the opposition even more. This puts us in a vulnerable situation, and it is frightening because we are confronting this regime head on.

KS: There are many actors in the United States with different interests and different abilities to make these decisions with what will happen with Juan Orlando Hernández. The State Department has consistently supported Juan Orlando Hernández, but you look at the Department of Justice, which is bringing forward these cases against Juan Orlando Hernández and his family, and then you have Trump and the chaotic nature in which he seems to be making decisions. So it’s hard to know what the U.S. will do.

I think the decision has already been made about whether Juan Orlando Hernández will be taken out of power or not. I don’t know what that decision is. And Hondurans are waiting for it. We are waiting to see just how much the Americans are going to put out information about the degree to which Juan Orlando Hernández was involved with his brother in drug trafficking and money laundering. Really incriminating information has already come out, but it remains to be seen if that will mean he has to resign or face justice or be extradited. I don’t think we’re going to know what’s going to happen until after the electoral reforms are dealt with.

In those electoral reforms, the issue of reelection has to be discussed. There’s no law that regulates reelection. With these electoral reforms, decisions are going to have to be made about whether Juan Orlando Hernández will stay his whole term, or whether he will step down after two years, and it is also an interesting opportunity to see what the U.S. will do. Will they put pressure on the Congress to get Juan Orlando Hernández out in a legitimate way, or will he be taken out through embarrassing information that comes out of the New York courts? I don’t think he’s going to last a year. But it’s hard to know because things change daily here.

NACLA: There’s no shortage of scandals to fuel popular outrage in Honduras. Recently there’s been the case of corruption in the social security institute and other high-level corruption cases, the 2017 elections stolen in plain sight, the deadly crackdowns on protesters, the political prisoners and constant criminalization of human rights defenders, the privatization of the health and education systems, and now JOH’s drug money ties. What’s the priority for the resistance right now?

EE: The demand from different social and political movements lately is for Juan Orlando Hernández to leave power. But we know that is not going to be easy, and it also depends on the U.S. State Department. It is a top priority, but at the same time, the political arm of the resistance is also preparing itself for the next battle at the ballot box. The struggle continues.

The people are organized, the mobilizations and different protests in all corners of the country from the north to the south and here in Tegucigalpa also continue. The call for unity from all organized social sectors of the country still stands, continuing to demand the removal of Juan Orlando Hernández, since his presidency is unconstitutional and illegal. The people did not accept the [2017] electoral fraud or his reelection, so he has remained in power by military force.

NACLA: There’s so much news coming out of Honduras and the region lately. What are the most important issues for folks with an eye to solidarity to be sure to pay attention to right now?

KS: The ongoing human rights crisis that started with the 2009 coup but got much worse after the 2017 electoral crisis is a huge priority. Also, political prisoners, which is part of the human rights crisis. There are still two political prisoners in prison and there are over 170 people who have to go before a judge and sign every week because of criminalization for protesting the electoral crisis.

The second issue is that the struggles in territories are becoming increasingly difficult. For example, in Vallecito—a newly-recovered Garifuna community in the last several years—the Garifuna organization OFRANEH is under serious threats of armed individuals that keep going into their territory and pressuring them to allow for criminal activities to occur on that land. COPINH is also facing significant threats in Río Blanco, where DESA [the company Berta Cáceres organized against] is still trying to exacerbate tensions in the community, and it’s getting worse. In the last three months, we are seeing that all these different struggles—against mining, against hydroelectric dams, for land reclamation projects—they’re all being attacked in a much more aggressive way.

Third, the Berta Cáceres case is a huge issue that still has not been addressed. Seven people have been found guilty, they have not been sentenced, they have not arrested the intellectual authors. Berta’s case is symbolic in so many ways; it always has to be a demand.

Fourth is the issue of drug trafficking and the narco-mafia government that is running Honduras. How can you deal with impunity and corruption if the highest levels of the government are involved in drug trafficking and money laundering schemes and stealing public funds? This issue is showing that Juan Orlando Hernández has less and less legitimacy every single day in the country. A lot of people think it is just a matter of time before he is taken out of power.

NACLA: Karen, you, your family, and supporters campaigned to get the Canadian government to speak out about political prisoners in Honduras. What has been the role of international solidarity in keeping eyes on Honduras and securing freedom for Edwin and other prisoners?

KS: International solidarity played a huge and critical role. Starting with my community in Canada, my mom and my neighbors and our community where I grew up formed the Simcoe County Honduras Rights Monitor to put pressure on the Canadian government. They made several trips to Ottawa to demand meetings with minister [of foreign affairs Chrystia] Freeland and to meet with members of parliament. They just kept chipping away, demanding Edwin be released along with all political prisoners and demanding that Canada pull support for the Honduran regime.

In the United States, the bases that make up the Honduras Solidarity Network played a fundamental role as well. When they went on hunger strike, we put out an action and within two and a half days we had over 2,500 responses and people who had sent emails to the Honduran, Canadian, and U.S. governments. There’s a European network as well that was constantly doing actions and fundraising for legal fees and medical costs. International solidarity was critical, and I don’t think we would have been able to the issue of Honduran political prisoners on the national and international agenda without it.

NACLA: How many political prisoners remain in jail right now and what kinds of conditions are they enduring?

EE: We—Raul Alvarez and I—still consider ourselves political prisoners, because we are still being processed, even though we are mounting our defense outside of jail. In jail, there are two compañeros, Gustavo Cáceres in El Progreso and Rommel Herrera who is in the Paraiso department in La Tolva prison, where we were. But there are also more than 180 people facing legal processes for political reasons who were jailed and then released to defend themselves outside of jail. They are still judicially persecuted and have to sign before a judge every week, like us.