On March 14, NACLA will be celebrating its 50-year history with a special gala fundraiser in New York City. Tickets are now on sale. Click here for more information.

In January 2020, news emerged that two of New Orleans’s famed Mardi Gras parades, Endymion and Zulu, were changing their routes in order to avoid the destruction wrought by the deadly October 12, 2019 collapse of the Hard Rock Hotel building just off of the French Quarter district. The rerouting most likely occurred due to safety concerns, yet the symbolism remains palpable—some of New Orleans’s dearest traditions literally turning away from the human lives lost in service to maintaining the city’s tourism economy.

Over four months ago, dozens of workers were injured in the collapse. Of the three who died in the collapse, only Anthony Magrette’s body has been recovered. The bodies of Quinnyon Wimberley and Jose Ponce Arreola, the latter a construction worker from Mexico, have yet to be recovered. Soon after the collapse, an undocumented migrant from Honduras, Joel Ramirez, who spoke out to the press about the shoddy conditions of the Hard Rock Hotel, was deported in retaliation for his whistle blowing.

As we noted in a New York Times op-ed in December 2019, this event encapsulates how post-Hurricane Katrina labor markets from 2005 on have undergone changes reflecting broader global trends: increased privatization and deregulation of the construction industry occurring hand-in-hand with a hardening approach to the rights of immigrants. Local law enforcement and ICE have become tools used to advance private development projects as regulation and risk shift from the developers onto the workers.

As a city reliant on tourism dollars—New Orleans earns approximately $7.5 billion from up to 17 million visitors per year—the commodification of decadent revelry and cultural authenticity has partially enabled a robust yet largely unregulated construction industry, ever open to job-seeking workers whose bodies, as this collapse shows, have become commodified and rendered disposable in a bid to keep New Orleans open for business.

Post-Katrina Changes and Continued Worker Precarity

Just a year after Katrina, a 2006 report showed that Latinx workers made up nearly fifty percent of the rebuilding workforce. These workers, the majority of whom were undocumented, conducted the risky tasks of initial cleanup and removal under toxic conditions. Wage theft, work injury, and other labor abuses due to poorly regulated work sites have characterized the building trades since Katrina. Additional insecurity due to the possibility of being deported is directly related to the economic precariousness that characterizes Latinx migrants working within the construction industry.

Several days before the Hard Rock Hotel collapse, a Spanish-speaking worker posted a video exposing the deleterious conditions of the structurally flawed building. With his phone, he captured footage of the temporary beams, bending at pressure from too much weight from the floors above. “Look, Papo, it’s the best engineering,” the worker said sarcastically in Spanish. Then, two days later, the upper floors of the thirteen-story building crumbled, causing dozens of pedestrians and approximately one hundred construction workers to flee for safety.

When Joel was detained for speaking out to the media against the worksite conditions, he was also one of five workers who initially filed a lawsuit seeking damages due to inadequate materials and protections. Despite being a key witness in the collapse of the hotel, Mr. Ramirez was soon deported.

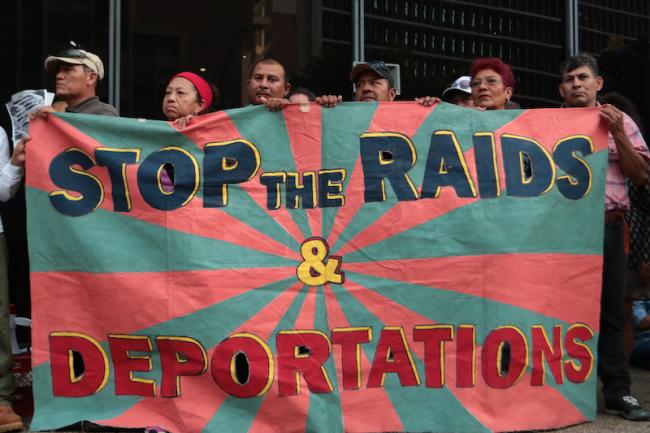

In the days leading to Joel’s deportation, a campaign spearheaded by the Congress of Day Laborers along with ISLA, pro-bono immigration lawyers, and union members aimed to stop the deportation. Despite this campaign—and objections from the director of the Louisiana Workforce Commission and local politicians—Joel was deported back to Honduras on November 29, 2019. He had lived in the United States for almost 20 years.

Joel now resides in a small town in Honduras, thousands of miles from his wife and three children. According to Claudia Mendoza of Univision, upon arriving home, Joel’s mother informed him that just two weeks after his detainment by ICE, his father died of a heart attack at the age of 72.

Joel remains in Honduras, a country that, like New Orleans, is often considered “open for business” due to the growth of extractivist industries like tourism. Similar to the rise of disaster capitalism that followed Katrina in New Orleans, Honduras, too, endured hyper-austerity measures that favored corporate investors after the coup that overthrew Manuel Zelaya in 2009. Such instances of political corruption make up the multitude of reasons why individuals like Joel have left Honduras for cities like New Orleans, and make it hard when they are forced to return.

Federal Complicity

In 2012, a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the Obama administration’s Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Labor (DOL) established that enforcing labor law “regardless of immigration status” was paramount and that Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) worksite enforcement would take into account whether or not tips were “motivated by an improper desire to manipulate a pending labor dispute, retaliate against employees for exercising labor rights, or otherwise frustrate the enforcement of labor laws.”

While the MOU moved towards de jure protections of the rights of all workers, by 2017, the Trump administration had removed these protections, replacing them instead with draconian policies meant to target vulnerable migrant workers. In particular, the Trump administration did an about-face on the DHS’s position on ICE, with an executive order calling for the abolishment of exemptions for “removable aliens” in a bid to “employ all lawful means to enforce the immigration laws of the United States.”

At the same time, DHS director, John Kelly, sought to massively expand the capacity of ICE enforcement by hiring 10,000 officers and agents in 2017. And, in 2018, federal worker protection agencies, such as Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), remained understaffed despite a 10-year high in worker deaths, thus increasing the vulnerability of this undocumented workforce twofold. By prioritizing harsh immigration enforcement over necessary worksite regulation, the federal government has given permission for private industry to employ workers who are vulnerable on multiple fronts.

Just after Joel’s deportation, the director of the New Orleans Workers’ Center for Racial Justice joined forces with the Louisiana AFL-CIO director to pen an op-ed in The Advocate calling for the City Council to protect vulnerable workers and to regulate developers and contractors. Despite these pleas, there has yet to be an open hearing about the case. And the same developers remain in charge of cleaning up their own mess with little oversight and no public input, with some exceptions, like calls for accountability by the Committee for Public Hearings on the Hard Rock Hotel Disaster.

Enabling Graft, Deregulation, and Urban Neglect

These policy changes bring us to the October 12 collapse and the state of New Orleans’s political and economic elites. The website of Citadel Builders LLC—the company contracted to build the new hotel by Kailas Companies, the Hard Rock Hotel development owner—features a definition of citadel: “a strong tower, a fortress, in a position of strength over a city.” In light of the recent deaths and injuries, the irony is unmistakable.

Jules Bentley’s exposé on the Hard Rock Hotel collapse, “Built to Kill,” shows the corrupt linkages between developers and city officials that enabled this structural disaster. In 2013, a Kailas family member pled guilty in federal court to overbilling the aforementioned Road Home program in the aftermath of Katrina. These are the same developers that are in charge of structurally unsound construction projects. Often hiding behind the protections of their LLCs or through the creation of new LLC names, accountability and regulation escape these developers, further contributing to the proliferation of dangerous worksites.

Mayor Latoya Cantrell, a Democrat, was initially heralded for quick action in response to the Hard Rock Hotel collapse, although an investigative report by The Lens revealed that her office accepted almost $70,000 in political contributions routed through 1031 Canal Street LLC—Mohan Kailas’s company behind the construction of the Hard Rock Hotel.

As investigations continue, the graft, neglect, and collaboration between city officials in conjunction with developers—and further backed up by an emboldened ICE and underfunded Department of Labor)—become increasingly clear. New Orleans’s FOX8 broke a story on February 20 using GPS tracking devices to expose how three different city inspectors likely signed off on the construction site without actually ever visiting the site.

What Does This All Mean?

In a recent collection, Remaking New Orleans: Beyond Exceptionalism and Authenticity, Adolph Reed Jr. concludes, “In New Orleans, that politics of representation dovetails conveniently with both the reigning discourse that touts cultural heritage and diversity and a local political economy based on redevelopment and marketing through invention of cultural authenticity—it’s no accident that the city now boasts a traditional festival nearly every weekend and a second line every day—and shaped through competition over recognition and standing for grants and contracts.”

Mardi Gras parades have traditionally been adept at addressing topical issues through humor. Footage recently emerged of a particularly cruel float mocking the collapse of the Hard Rock structure with the tagline in royal purple proclaiming: “That’s a little mushy.” Not surprisingly, the demolition of the Hard Rock building will only go forth after the culmination of Mardi Gras on February 25. Nonetheless, New Orleans residents and tourists will take to the streets to celebrate the very cultural heritage that ensures a steady stream of revenue in tourism dollars. Not only must the Carnival party go on, but it must go on with the dereliction of the powerful ignored and the bodily sacrifices of low-wage workers out of sight and out of mind of the thrill-seeking public.

Sarah Fouts is an Assistant Professor in American Studies at UMBC, currently working on a book manuscript on labor, food, transnationalism in post-Katrina New Orleans and Honduras. Fouts's work has been published in NACLA, Gastronomica, Journal of Southern History, and the Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. Fouts has a PhD in Latin American Studies from Tulane University and an M.S. in Urban Studies from the University of New Orleans.

Deniz Daser is an anthropologist who studies migration, labor, and citizenship under conditions of insecurity. She is a visiting research associate at Rutgers University, where she completed her Ph.D. in anthropology in 2018. Her dissertation, “Leveraging Labor in New Orleans: Worklife and Insecurity among Honduran Migrants,” is based on 18 months of ethnographic field research and archival study in post-Katrina New Orleans.