On March 14, NACLA will be celebrating its 50-year history with a special gala fundraiser in New York City. Tickets are now on sale. Click here for more information.

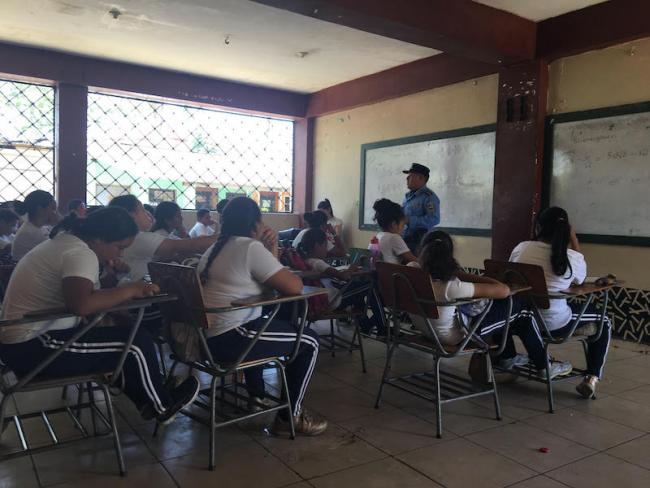

A Honduran police officer, clad in blue uniform and with a gun at his hip, stands at the front of a packed classroom of eighth grade students in a school in one of the marginalized neighborhoods of the northern city of El Progreso.

Officer Martínez* was trained by U.S. military officers to conduct a gang and violence prevention program at this Honduran public high school, where problems with gang violence are an ongoing battle for both students and teachers. Honduras is one of the most violent countries in the world, with street gangs like MS-13 and 18th Street controlling most peri-urban barrios like this one. Students frequently drop out of school—voluntarily, by force, or by necessity—to join these groups.

Gang Resistance Education and Training, known as Project GREAT, is a police-taught gang and violence prevention program architected in Phoenix, Arizona, which has been exported in recent years from the United States to Central American countries, including Honduras. The program’s website describes it as “an evidence-based and effective gang and violence prevention program built around school-based, law enforcement officer-instructed classroom curricula.” In Honduras, it has two key aims, striving not only to provide youth with the necessary skills to “avoid gangs and violence,” but also to help form better relationships between young people and local law enforcement officers. Nearly 87,000 students reportedly participated in the program in Honduras in 2017.

“[By] working with young people, we hope to reduce violence, so that students don’t sell drugs, don’t get into gangs,” Martínez explained. “We don’t have much experience, but what we have achieved with the programme [so far] has been very successful.”

Through the open window, the class’s teacher looks in. For some of the police officers, this is their first time in a classroom.

A School on a Fault Line

Located in a barrio on the outskirts of El Progreso, Honduras’s fourth largest city, this high-school boasts a student body of just over 4,000 from grades 7 to 12 and split into morning, afternoon, and night shifts, as well as roughly 150 teachers and administrators. The institution is one of the largest public secondary schools in the city, and most of the student body comes from peripheral, heavily stigmatized neighborhoods that suffer from particularly high rates of violence and where state presence is often fractured. Zonas calientes, one student calls them: hot zones.

The school grounds are large and open, with classrooms built around two courtyards with several glorietas (kiosks) and concrete tables and benches. A new art teacher has gotten students involved in painting murals, so colorful paintings adorn many of the school’s walls. Several teachers were quick to point out that the school’s buildings—except for the original one, which was built when the school was founded—had all been paid for by foreign embassies and other external bodies, including Japan and the European Union, not by the government.

Not immediately apparent however, is the fact that this particular public school is located on a fault line between MS-13 and 18th Street gang territories, often referred to simply as la MS or la trece and la dieciocho. Scrawled 18s, 13s, XVIIIs, and XIIIs adorn the school’s walls, benches, desks, and doorways.

“We belong to the Mara 18. This territory here, this school, is controlled by la dieciocho,” explains Patricio, one of the school counsellors. “But from that wall over there it belongs to la trece. And right now, there’s a fight over territory between these groups, and the students are in the midst of the conflict, and the teachers are in the midst of the conflict too. Right now, we’re living in a situation that’s worse than ever, so we’re just waiting for a tragedy to happen at this school. Things are hot right now.”

The school’s director says this conflict concerns him greatly, though it doesn’t surprise him. “This school is in the middle of some of the most conflictive areas there are here in El Progreso,” he says. A focus on school security in the three years since he has taken over, including the installation of several security cameras, has calmed the situation in some respects—there are no longer as many gang-related fights occurring on campus, for example—but tensions continue to run high.

“The role of the police, especially here, is to prevent,” the director explains in reference to Project GREAT. He adds that it is also unprecedented. “We don’t usually have police or military inside classrooms, but given the circumstances that we are living in at this moment, it is important that the police themselves come and give [the students] a talk.” He spoke with a note of underlying skepticism, but also an openness to try.

Teachers Push Back

While effective violence prevention is an urgent need in Honduras’s vulnerable communities, the program has met resistance among public school teachers, who have questioned whether this U.S.-supported program is truly helpful or merely superficial window dressing designed to foster a positive image—of the Honduran police, the Honduran government, and the United States.

The impact of U.S. meddling in Honduras is ever-present: The Obama administration backed a military coup in 2009 that grabbed power for conservative elites, and the Trump administration endorsed the contested outcome of a presidential election widely condemned as fraudulent in 2017 that locked in another term for president Juan Orlando Hernández, who is accused of drug trafficking links. Given this damning U.S. record of intervention, the program’s U.S.-created curriculum, U.S.-trained police officers, and U.S. funding make many teachers immediately skeptical of the program’s intentions. High levels of distrust of the Honduran police force, due to their frequent involvement in violent repression of popular protests and a reputation of rampant corruption, only adds to this negative perception.

Teachers at the El Progreso school crowded into a classroom for the staff meeting where Project GREAT was to be announced. At the front of the room, a slideshow projected images of smiling uniformed officers onto a rickety whiteboard.

The group of police officers who would be running the program began explaining the program’s aims, while teachers looked on with narrowed eyes.

After the presentation, the educators fired off a round of seemingly unending—and, for the police officers, unanswerable—questions: Why were the police so violent when suppressing protests but were now here to work peacefully with youth? Why were the police not helping the young people who weren’t in school who were arguably those most at risk, instead providing support to the ones who were easy to reach? Why do police not arrest gang members in communities where everyone knows who they are?

Several teachers spoke with passionate defiance and were met with applause by others. Two of the younger police officers became visibly uncomfortable.

“It’s not easy to come here as policemen, dressed in our blue uniforms, in a school when we know the perception of the police is not positive,” one of them said. “But our mission is not political, it is apolitical.”

Several teachers laughed.

In a study on the program’s impact in the United States, researchers found that its effect on children was, in fact, minimal. However, the researchers noted that the program would “continue because of the powerful symbolic political and public relations utility it has for various stakeholders.” Before police officer even held the first session, it seemed clear to teachers that the same was now happening in Honduras.

Belying its stated intentions, the top “success point” listed on a slide about measuring the program’s success involved cultivating “more positive attitudes towards police.” This raised further questions among teachers as to whether the program was really about supporting youth or serving as a political tool.

Political or not, however, the school’s director had already agreed to the program, and so it began just days later.

The First Session

In the first GREAT session—a pun missed by all but a few of the Spanish-speaking staff and pupils—each student received a manual with reading exercises and multiple-choice and fill-in-the-blanks questions meant to assess comprehension. The manual was full of pictures of non-Latinx students in schools with windows and carpets with little resemblance to their own classrooms—apart from translation into Spanish, the materials clearly hadn’t been adapted to the Honduran context.

The sessions involved lots of reading aloud—usually by the police officers, not students—choral chanting, and copying off the board. When a student tried to give a definition of a word that differed from the one in the official answers manual, the policeman leading the session simply said “no” before reading out the correct answer. Despite some training, the police officers were clearly unequipped to deliver an educational program, making it questionable how such a method would help students desist from gang involvement.

The Politics of Funding

The fact that police officers—a U.S.-funded force and a proxy of the Honduran government—are responsible for implementing the program points to the initiative’s political nature. But the direct funding of Project GREAT and who benefits from the image it constructs also reveals the program’s underlying political motivations.

Both the Honduran and the U.S. governments arguably benefit politically from violence in Honduras: For the Honduran government, widespread corruption and involvement in the drug trade become easy to blame on gangs, keeping high-level direct involvement in illicit activities in the shadows. In the case of the United States, widespread violence legitimizes the presence of U.S. military bases, high levels of security funding and war on drugs strategies, and the significant degree of U.S. political influence. Violence proliferated in Honduras amid general lawlessness in the wake of the 2009 U.S.-backed coup.

However, when crime rates are as high as they are, optics are important: Both countries need to create the perception of making a concerted effort to combat this violence to defend their legitimacy, even while their strategies may undermine stated efforts of reining in violent crime. Perhaps that is what Project GREAT does: superficially attempt to conceal the reality of national and international involvement that fosters and drives violence, while making it seem like they are fighting it.

As countless teachers put it, Project GREAT is simply “maquillando la situación”— applying makeup to the situation—while not actually changing anything.

“It's a superficial program,” said Miguel, one of the high school teachers, after watching the first month of the program play out in his classroom. “Yes, maybe it will help some students, but it is mostly the image that says ‘yes, look what the police are doing.’ But the police know that these areas are full of mareros (gang members), but are they doing anything? Ha! And also, it’s a program funded by the U.S., but what is the role of the U.S. with a lot of countries? Just selling weapons! So…” he shrugged and gave a knowing look.

Side-lining the Needs of Youth

Project GREAT’s political nature does not necessarily render it entirely useless for the students it reaches, but it is clear that the focus is on improving a political image, rather than on how problems can best be solved.

Honduras’s youth need many things: greater investment in education and learning opportunities, employment prospects, and a government that respects democracy, to name just a few. Last year, protests erupted across the country to reject government plans to privatize the country’s health and education systems—a testament to the government’s bankrupt approach to investing meaningfully in students’ education. Increasing police presence in schools and promoting a positive image of a police force still rife with corruption and mismanagement, where the same police officers teargassing students in protests come into their classrooms to give them definitions of terms they know all too well from their day-to-day lives, is unlikely to lead to long-term change.

Ultimately, Project GREAT is expanding not because of the needs of youth, but because of a desire to promote a positive image of the police and the U.S.-supported Honduran government.

*All names are pseudonyms

Antonia McGrath is a writer, non-profit director and freelance journalist whose work focuses on violence, oppression and human rights in Central and Latin America. She holds a Masters in International Development Studies from the University of Amsterdam and a BA in International and Latin American Studies from Leiden University. She can be reached at antoniamcgrath@gmail.com and antoniamcgrathblog.wordpress.com.