Venezuelan police forces murdered Cristina’s son Dario nearly 10 years ago, on August 25, 2010. The date was not only her murdered son’s birthday, but it also became the beginning of a ritual search for justice.

Cristina heard the shots that killed her son. She witnessed how the authorities assembled a “movie,” manipulating the crime scene. Police moved the body from the site of his murder and shot into the air in the opposite direction. They put a weapon in his hands, to allege that he had resisted the authorities.

Since that day, Cristina has been looking for answers. Her everyday life became a journey to find justice for the assassination of her son. Day after day she visited public institutions, finding no answers but continuing her fight to move the case forward.

One year later, the judicial process stagnated. A decade after his death, nothing has changed. “Every time I go to the District Attorney’s Office, they tell me I have to come back the next week,” she says. “I go the next week and then the next. Can you imagine?”

She is rightfully concerned. “With the cost of transportation right now… …it is just impossible,” Cristina says. “Whenever I need to go, I think about the cost of taking the bus. I think about it all the time.”

The mainstream narratives of suffering in Latin America fall into a dichotomy of heroism or tragedy. Stories like Cristina’s offer a more intimate lens, emphasizing how power has marked trajectories in her life. These small daily obstacles, like not having money for transportation or having to decide between seeking justice or feeding her children, reveal deep tensions in her personal experience.

Security forces in Venezuela kill young men with impunity. A group of women in Caracas has organized to support each other in their search for justice. I documented the everyday struggles they face to hold the state accountable for violence against young, poor residents of the barrios.

During her quest for justice, Cristina began meeting other women at the prosecutor and ombudsman offices whose sons had also been killed by police officers. We would see these women by the plazas waiting and lying on the street. “Look, they also came here to search for justice. Can you see them with their bags and their tired faces?” Cristina asked me while walking downtown.

“There was a time when I began to see so many women with their little boys, young women, and I asked myself: My God, what is happening?” It was 2015 and the Operación Liberación del Pueblo (People´s Liberation Operation), a police and military incursion to barrios and rural sectors had begun as a new citizen security policy, further militarizing society.

“I remember all the women calling me, they had no idea what to do about all the killings in the slums,” says Cristina. “They didn’t know where to go for help. At that point, we began to organize ourselves better.”

It became clear that the subsequent police killings were not due to a few “bad apples.” It was rather a political decision to use lethal force to bring “security” to the barrios. A whole new military set of terms was used to characterize the security situation in the poorest areas. Ordinary crimes were labeled as paramilitary acts. Streets in the slums were named as dead rows, or “corredores de la muerte.” Police killings were renamed as acts of “resisting authority.” Citizens came to be seen as enemies to be neutralized.

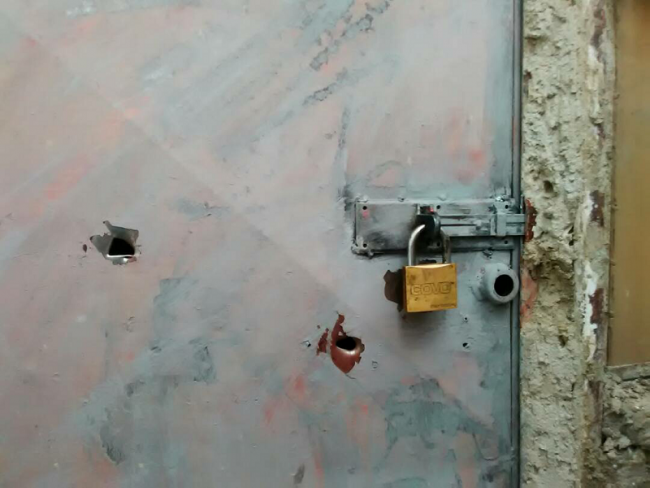

Cristina and other women organized a group to support victims of police operations. The task was complex. As some victims say: “The police officers are supposed to take care of us, but instead, they are the assassins of our sons.” The experience of losing a son at the hands of law enforcement creates feelings of profound ambivalence, suffering and silencing. “We did everything that’s possible: protests, barricades, media reports, but they, the institutions, never listen, nothing happens.”

In their cases, the execution of justice depends on the same security and justice institutions that hold the officials responsible for the deaths of their sons. “Firefighters do not step on each other’s hoses,” is a popular saying that women use to refer to the fact that police officers do not investigate and prosecute other police officers. The women distrust the justice system, but fear taking actions that expose and denounce the killings because of possible reprisals.

During this process, the women have received threatening phone calls and messages form social media. No one protects their safety; they are on their own.

Intimacy as a Space for Politics

Latin American history is plagued with authoritarianism and lethal violence. In response, different movements of wives and mothers of victims have emerged. Historic examples include the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo and, more recently, las Madres de Los Falsos Positivos de Soacha in Colombia. They demonstrate the power of the figure of mothers.

Through the ethnographic approach to the intimacy of Cristina and other women, I understand these figures as profoundly political. Being mothers signifies a public role in a political stage; in this scenario, being a suffering mother serves as an amplifier to give some echo to their voices in a society that ignores the reality of police killings.

Through the work of anthropologists Bergoña Aretxaga and Shaylih Muehlman, we can understand how the women that lead a political struggle must show their subjectivities as suffering beings, who grieve, care, and worry about others. At an intimate level, they live with ambivalence and ambiguity given all the years of waiting without answers and support from the state. Some come to blame themselves for the killings: “Could I have gotten my boy out of the barrio? Could living in a better neighborhood have saved them?”

All these questions cause them pain, while those responsible remains exempt. The state remains untainted while motherhood and femininity are questioned. Could a woman still be heard even if she does not show herself as a suffering subject? Will her voice echo if she speaks in other positions besides pain and grief?

With the permission of these mothers, I created an intimate record of their struggle. I found other kinds of fights and tensions that are hard to resolve in their daily life. Some portraits of the struggle of women against dominant systems, as the state or the patriarchy, create romantic ways of seeing the possibilities of resistance. The women emphasize how they move between the exclusion and suffering to bring light to their stories. This allows us to see how law enforcement power penetrates even the most private spheres of their lives. These women do not seem tired despite the great obstacles they face. But their lives demonstrate a profound precarity.

Being solely a victim is not an option. They reject these categories by making it clear that "I am not a victim, I am something else" or "Of course I am a victim, but I am strong." Even in the precariousness of their situation, they maintain their agency.

Militarized Quarantine Constrains Action

The social and political scenario in Venezuela has many difficulties and challenges. There is no resolution on the horizon to the political struggle between the opposition and officialism. The humanitarian crisis, a collapsed economy, and declining oil production all shape the political reality. These factors make alternative discourses less available to the people.

On March 14, Nicolás Maduro’s government imposed a national lockdown, closing all schools, workplaces, and recreational activities as a measure to contain the spread of Covid-19. This quarantine, when seen through a micropolitics lens, reveals the limitations of social movements, especially those with no political affiliation. Military and police forces enforce the quarantine. As Veronica Zubillaga shows in her work, this militarization of the pandemic means less civil participation in political decisions. Recently, the government has decreed the return of migrants from Colombia as a public health problem.

For the women seeking answers in their sons’ deaths, their work is unfeasible in this context. They cannot move within the city, and many of them do not have cellphones and internet service. Some of them were afraid to go to the barrios, and others do not have money for transportation. The quarantine has exacerbated the precarity of everyday life. For these women, only their ties to each other keep alive their faith in change.

Francisco Sánchez is a professor at the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello in Caracas and a member of La Red de Activismo e Investigación por la Convivencia (Activism and Research Network for Coexistence, REACIN). He is conducting field work on violence, vulnerability and health in Caracas.

He would like to thank Laura Botero, Rebecca Hanson, Natalia Gan, and Olivia Page-Pollard for the support and kind comments and the advices on translating the text.