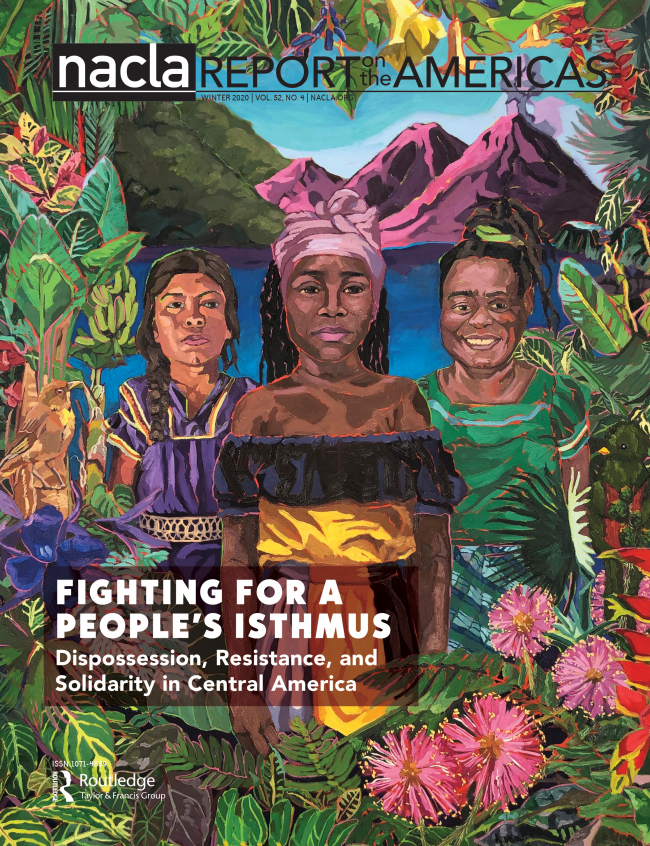

This piece appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

In a 1973 issue on Central America, NACLA published a piece detailing how U.S. aid created, then destroyed, the Central American Common Market. The case showed, as author Susanne Jonas put it, how aid serves “as a means of manipulating people and governments in Central America to suit the particular needs and whims of U.S. corporate interests.” But it was also “a story of contradictions, a demonstration that the mechanisms of capitalism sometimes do break down almost of their own accord, or as a result of conflicts among the dominant groups.”

After decades of free market policies, U.S.-backed militarization, and a failed promise of peace baked into the region’s weak institutions, the systems reproducing Central America’s multiple crises have yet to destroy themselves. In the November/December 2000 issue of the NACLA Report, human rights scholar Jo-Marie Burt, a former NACLA editor, identified a key lasting feature of global politics despite post-Cold War changes: the world capitalist economy. “It is this paradox of change and continuity,” Burt wrote, “that has confused observers of the post-Cold War era, leading many—a few skeptical progressives aside—to assume that international conflict was a thing of the past, and that Washington would cease its imperial ways.”

Two more decades on, the conditions that gave rise to Central America’s conflicts persist, while the promises of postwar peace and democracy have fallen flat. Interventionist U.S. foreign policies wrapped in the rhetoric of stemming migration, waging war on drugs, and stoking development continue to enable militarization, human rights abuses, and displacement. As William I. Robinson details in his feature essay in this issue, the reverberations of the crisis of global capitalism now push the region to the brink of a renewed collapse. And in a world hurtling toward climate catastrophe, Central America is one of the most vulnerable places.

When civil wars and U.S. military intervention ravaged Central America in the 1980s, international headlines kept an eye on the region. That time also marked an important period for the U.S. Left. On the heels of movement against the Vietnam War, solidarity with Central America budded in the early 1980s as the Contra War got underway in Nicaragua and military governments in Guatemala and El Salvador oversaw the most heinous massacres of those countries’ bloody civil wars. Over the next years, as our From the Archives excerpt in this issue details, tens of thousands pledged to resist heightened U.S. military intervention in the region.

At the time, the U.S. government propped up regimes responsible for atrocities so vicious and a disregard for the rule of law so blatant that basic demands for human rights and democracy formed a broadly unifying solidarity agenda. A cohort of activists came of age in the effort. Once peace agreements halted the bloodshed in Guatemala and El Salvador and set the transition to democracy in motion, however, coherence around positions supporting the region’s political future proved more elusive. In his 2019 book Solidarity, Steve Striffler argues that these challenges grew largely from the movement’s primary grounding in pressing human rights issues, not a long-term vision of Left internationalism. Broad-based solidarity dimmed, while U.S. economic interests and transnational corporations salivated over the newly pacified region and worked to impose a development doctrine that ensured access to its resources.

In recent years, Central America has again garnered heightened U.S. mainstream media attention. Propelled mostly by immigration “horror stories,” as the title of a recent piece by journalist Felipe De La Hoz for The Baffler put it, this renewed coverage has offered up a parade of suffering. Crying Central American children pleading for their parents, a mother and her children fleeing teargas, a man and his daughter drowned in the Rio Grande, and other depictions of collective trauma have gone viral and sparked outrage. Although deep reporting of the family separation policy and Central American exodus has helped shed light on the complex problems pushing people to take perilous journeys, much of the major coverage of Central Americans and their homelands remains shallow or sensationalized. And Central American stories and geographies that fall outside limited migration narratives often don’t make the news at all.

Journalist Roberto Lovato, whose new book Unforgetting is featured in our Reviews section of this issue, wrote in a 2018 piece for Columbia Journalism Review that many of these mainstream depictions “end up minimizing the systemic, long-term crisis at the heart of the Central American migration story.” That larger story includes decades of U.S.-backed war and militarization, the wreckage of economic imperialism, and increasingly, the impacts of a climate crisis brewed in the Global North. But it also includes, Lovato argued, human experiences beyond violence and suffering like “determination, humor, [and] resilience.”

This NACLA Report reflects on Central America’s past, present, and uncertain future. Migration is interwoven in these stories, and many authors offer incisive analysis that can enrich understandings of why Central Americans leave their homes. Yet this is an effort to dissect a broad range of challenges, beyond questions of migration, plotting the region’s course. Authors grapple with the multiple and intersecting crises of the failures of neoliberalism, government corruption and mismanagement, political manipulation of grave security issues, climate chaos, and unfinished historical reckoning. They also distill Central Americans’ resilience and resistance in confronting these crises in each country of the Isthmus, providing ample food for thought for rethinking solidarity in the 21st century.

Continue reading the rest of the Editor's Note here. You can view the table of contents here.

Heather Gies is managing editor of the NACLA Report.