This is the fourth article in series on child migration from the Infancias y Migración Working Group. New articles go up on Fridays.

Para leer este artículo en español, haz clic aquí.

In Valparaíso, about two hours of the Chilean capital of Santiago, two police officers arrived at the home of Nelly Reyes in 2015 with a surprising piece of news: “There is a son of yours who is looking for you.”

Reyes, confused, explained to them that this was impossible because all her children were there with her. The police officer replied, “No ma’am, your son is named Travis Tolliver. He’s 41, he lives in the United States, and he’s looking for you. You put him up for adoption in the Dr. Enrique Deformes Hospital.”

Nelly was forced to relive the tragic memory of November 1973 when, at 19, she gave birth to her first child. However, the hospital informed her that her son had died due to health problems. She never saw his body. Learning that he had been adopted in the United States and that he was looking for her immediately filled her with joy and the desire to hug him. Travis had traveled to Chile to find his mother and his family, hoping to make up for lost time.

Over the next five years, newspapers and television reports have repeated Nelly and Travis’s story many times. Likewise, various accounts have emerged of mothers searching for their children, many of whom have come from abroad with the hope of finding their biological families. In response to the great number of accusations of Chilean children adopted abroad without the knowledge of their biological families, in 2015 birth mothers and adoptees founded Children and Mothers of Silence. The group has since developed a systematic process of lodging complaints and assisting with family reunifications.

Journalistic investigations by CIPER Chile made the issue of the abduction of children for adoption public in 2014. They accused Chilean priest Gerardo Joannon of being one of the parties responsible for these practices. Known as “irregular adoptions,” these abductions consisted of institutional arrangements (medical-judicial-custodial) that forcibly separated children from their mothers either upon delivery or in nurseries and children’s homes. The objective was adopting them into families considered more suitable for their upbringing. Thousands of cases, concentrated during the 1973-1990 military dictatorship, reveal the establishment of a systematic mechanism of forced transnational adoptions. Dictatorship officials promoted the adoptions to improve the standing of the Pinochet regime, whose human rights violations had made it a pariah within the international community. Decades later, many questions remain about what responsibility rests with the state and what relationship these adoptions have to the military dictatorship.

Investigating Forced Transnational Adoption

As a result of social pressure and public interest, in 2017 the Chilean government launched an investigation. Initially, legal actions centered on a Swedish adoption organization accused of irregular adoptions of children destined for Sweden. The following year, the lower house of Chile’s Congress formed an investigative commission, which documented 8,000 accusations of irregular adoption.

It is impossible to verify how many children left the country for adoption abroad through these practices. However, the international literature concurs that Chile was one of the main countries of origin of children adopted internationally during the 1970s and 1980s. Laws governing adoption at the time did not include provisions for international adoption, which ended up facilitating these arrangements.

Under the military regime, Judge Gloria Baeza, chief of the Chilean Office of the Minor, implemented the National Child Plan, which sought to increase and facilitate adoptions as a response to the poverty that limited the regime’s economic plans.

The Plan sought to generate a “widespread adoption publicity campaign.” Baeza made the government’s position clear in a March 6, 1978 statement: “There is no regulation prohibiting the delivery of minor nationals to non-resident foreigners. The current tendency is for adoption, being a benefit to the minor, to have no borders.”

According to this policy, the international adoption institutions that were operating in Chile—New Opportunities Foundation (United States), the Centro Italiano per l’Adozione Internazionale, and the Adoption Center of Sweden, among others—“should be encouraged.” (Judge Gloria Baeza, resolution 279/1978, Ministries of Justice) Moreover, these institutions became allies to carry out the policy, which was ostensibly aimed at addressing the precarious situation of so-called “irregular minors.”

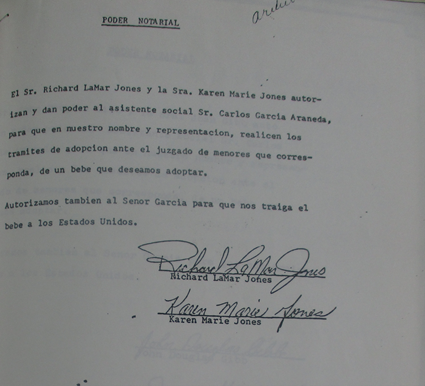

Family reunifications and the documentation that the adoptees possess have revealed lists of agents involved in the abduction and foreign placement of children. A whole series of public officials and private professionals worked to carry out the adoptions, including social workers, doctors, lawyers, and judges. In their roles in public institutions, these individuals would inform mothers of the “deaths” of their newborns, or in the case of nurseries and children’s homes, they would simply deny mothers information about their children’s whereabouts.

After abduction, the institutional procedure for leaving the country’s borders required validating a protective measure in the courts. Officials from the Ministries of Justice and Foreign Affairs certified that the children were “minors in an irregular situation” and that their mothers were unable to care for them. Typically, these judgments highlighted the mother’s poverty or her unfavorable moral and sexual behavior. In response, the judges granted custody to a recruiter on behalf of the adoptive family and authorized the children to leave the country.

In testimonies of those affected, many adoptees recall having traveled alone as children, under the supervision only of a flight attendant. In the destination country, representatives of the organization that arranged the adoption received the children and delivered them to their adoptive parents. Adoptions were subsequently finalized with institutional backing according to the legislation of each country.

Grappling with the Causes of a Painful Past

Economic motivations emerge as central to this system. From 1975 to 1986, professional mediators received between $6,500 and $150,000, to facilitate each adoption. In addition, even the state institutions that had children under their “protection”—that is, that had the power to make them available in this international circuit—benefitted through a system of “donations” for each adoption.

In addition to economic factors, the ideological foundations of public officials’ arguments were particularly important. These arguments were made to disqualify mothers—mainly young, single, impoverished mothers—from parenting, which was a determining factor that made abducted children’s adoption in another country possible.

In 1983, a press release reported that Ruth Reyes, then a 17-year-old single mother of two, had lodged a criminal complaint against Judge Ivonne Gutiérrez in the city of Valparaíso. Ruth affirmed that as a result of her difficult economic situation, she had gone to the judge seeking to temporarily admit her children to a children’s home. The authority permitted her to only admit her youngest child, aged 14 months. Ruth brought her infant to the judge’s house in Santiago with the promise that she would be able to visit her. Ruth signed various papers without fully understanding their content. She returned repeatedly to see her son, but each time the judge denied her a visit. According to Ruth, the judge said with a “threatening and mocking” tone that Ruth should not ask about her son anymore and that if she insisted, the judge would have her incarcerated, since “as a judge she could make decisions about kids, children of women like me, and that I had to keep quiet.”

Although this practice and tone were not new, during the dictatorship the fear of state institutions paralyzed many mothers. Meanwhile, the impact of the 1980s economic crisis, during which the Chilean GDP contracted by more than 14 percent and unemployment reached 30 percent, worsened the living conditions of poor and working-class Chileans. In this context, many women resorted to nurseries and children’s homes so they could go to work.

In contrast to Argentina, where abductions targeted the children of political dissidents, in Chile, such kidnappings involved very poor children. Yet the abduction of Chilean babies also had a political character and was tied to the dictatorship’s social welfare policies. This character was expressed when the regime’s authorities warned of an increase in illegitimate children born to single mothers who were still minors. According to official data, during the dictatorship the number of live births decreased, dropping from 250,462 in 1974 to 218,581 in 1978.

During the same period, so-called illegitimate births, to single mothers younger than 19 years of age, increased from 13,354 to 16,085. These “illegitimate” children and their increased numbers contradicted the military regime’s family values and aspirations for economic development. Any response to the problem of “minors in irregular situations” was made more complicated by the progressive decrease in public spending for child protection. Thus, transnational adoption emerged as a forced migration of poor, illegitimate children who were irreversibly separated from their mothers in the context of the military regime’s social control and neoliberal privatization of child protection.

Forced transnational adoption allowed the dictatorship to maintain diplomatic relations despite international condemnation of the regime. The presence of adoptive children in countries with high concentrations of Chilean exiles, who constantly denounced state terrorism, was particularly relevant. Adoption was part of Pinochet’s campaign to promote Chile and its culture and to reverse its negative image abroad.

The parliamentary commission created to investigate accusations of irregular adoptions called for the creation of a Truth and Reparation Commission on this matter. But it also highlighted the need to transform one of the worst legacies of the civic-military dictatorship: the paradigm that continues to criminalize poor families to this day.

Recovering the stories of children who experienced forced migrations through transnational adoption allows us to unveil the political role of childhood and situate children’s experiences within a historical context. This history also illuminates a cross-border institutional framework that allowed the separation of these children from their mothers. This past cautions us about various forms of dictatorial violence, but it also demands that we critically confront the development of transnational adoptions in the present.

Karen Alfaro Monsalve, PhD in Social History and Contemporary Politics, Academic of the Institute of History and Social Sciences, Austral University of Chile, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0162-8882, Researcher in charge FONDECYT-CONICYT Nº11170633 Project: "Saving poor childhood, Chilean children adoptions under the military dictatorship."

About the Working Group: In July 2020, the authors convened the Infancias y Migración Working Group, consisting of 10 colleagues in five countries from a variety of disciplines. This series of articles for NACLA is the group’s first publication project. The previous articles are: Exiliados, Refugiados, Desplazados: Children and Migration Across the Americas, The Orgins of an Early School-to-Deportation Pipeline, and Guatemalan Child Refugees, Then and Now.