This piece appeared in the Spring 2021 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

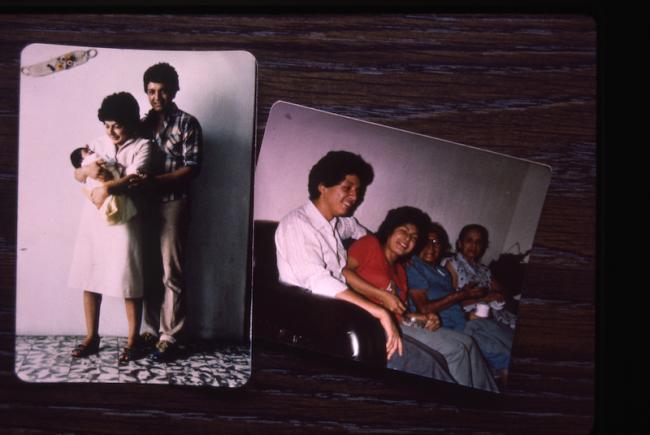

On February 18, 1984, Guatemalan police abducted Edgar Fernando García near his home in the capital city. His family, including his 18-month-old daughter Alejandra, never saw him again. Documents later revealed that state security forces, acting on orders from top government officials and in collaboration with the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, targeted García as an alleged communist threat. García, a 26-year-old engineering student and organizer at the public Universidad de San Carlos, was one of the 45,000 disappeared during the 36-year-long internal armed conflict.

In 2010, two former police officers were found guilty of forcibly disappearing and murdering García. But responsibility went higher up the chain of command, and in 2013, the former police chief and his subordinate were also convicted and sentenced for their roles in García’s disappearance. Archives were key in the prosecution.

Back in 1984, García’s wife, Nineth Montenegro, searched doggedly for her husband. “I wanted him back alive,” she testified during the 2010 trial. Together with other relatives of the disappeared, including García’s mother, Emilia García, Montenegro cofounded the Grupo de Apoyo Mutuo (GAM) in Guatemala City the year of her husband’s disappearance. The organization served as a support group and a source of legal aid for families victimized by political violence and widespread forced disappearances amid the country’s brutal armed conflict, then in its third decade.

Twenty-five years after the official end of the 1960-1996 conflict, efforts to establish peace and seek truth and justice for the more than 200,000 victims are still stalled and violently attacked. Guatemala’s archives contain evidence of state terror, including forced disappearance, systematic sexual violence, and genocide. As such, they are subject to repeated attempts to silence the voices within them. Archives not only play an important role in criminal trials in the aftermath of conflict, but they are also significant in continued efforts to dignify victims through affirming the truth of what happened to them. Edgar Fernando García’s case is one among approximately 3,300 documented incidents of forced disappearance in the GAM Historical Archive, and his story is an example of the ongoing need for truth and justice in Guatemala.

The Grupo de Apoyo Mutuo

The GAM is Guatemala’s oldest surviving human rights organization. The founders and earliest members were women; like Nineth Montenegro, they were mostly widows of disappeared activists, students, and others deemed “subversive” by the military state. Members and supporters of the GAM demonstrated in the streets of Guatemala City demanding the return of their loved ones, whose photos and names they held aloft on posters and banners.

They also collected denuncias (legal complaints) from family members of the disappeared and filed petitions of habeas corpus with the state. Through victim outreach, GAM compiled the 3,322 case files that now make up the Desaparecidos collection of the organization’s Historical Archive, housed in their office. GAM leaders earned the trust of victims and their families, collecting denuncias and testimony from the loved ones of the disappeared while providing psychosocial support services as a form of dignifying the victims.

Disappearances are acts of violence multiplied. The original acts of kidnapping, imprisoning, torturing, and murdering are compounded over lifetimes as those responsible walk free and often go unnamed. State institutions’ denial—of both their complicity and their fundamental legal obligations to provide loved ones with answers about the violent taking of victims—deepens the trauma. Victims are twice absent: they do not return home, but nor are their bodies presented for mourning. Their absences are open wounds of loss.

Little remains of the strength of the early years of collective struggle. The women who founded the GAM, like García’s wife and mother, initially spent entire days and nights searching for their forcibly disappeared loved ones. Cofounder Montenegro later moved her fight to working within the system, leaving the GAM to serve as a member of Congress from 1996 to 2020. Her husband, Mario Polanco, is the GAM’s current director. Some families are still searching decades later for victims whose whereabouts remain unknown, their bodies never found despite years of looking in hospitals, police stations, morgues, and cemeteries. In some cases, the GAM’s files of denuncias and testimonies are the only remaining evidence of these grave human rights violations. The generation that knew the disappeared is growing older. Many have not and will not see justice for their losses in their lifetimes.

Since its founding, the GAM has faced repeated efforts to silence its work. During the 1980s and 1990s, government and clandestine forces tried to erase all evidence of the atrocious acts committed during the 36 years of internal war. Between 1989 and 1993, the GAM offices were raided on two occasions and its facilities suffered three bomb attacks, leaving significant material losses. Some of the case files that contained testimonies were destroyed, further reducing families’ opportunity to learn the whereabouts of their loved ones and demand justice. Despite these attacks, GAM’s commitment to families has endured.

Now a non-profit civil society organization, the GAM focuses on strategic litigation, legal advice on historical and recent human rights violations, and the linkages between historical memory and transitional justice. The organization also works on transparency, such as obtaining information on violent crime rates and other issues of public interest and sharing it widely through regular press conferences. Aided in recent years by new international alliances, the GAM has expanded its work in historical memory. In 2015, GAM members and coauthors Daniel Alvarado and Carlos Juárez, human rights advisor and archive coordinator, respectively, began the restoration, preservation, and classification of the more than 3,300 denuncias of forced disappearances and approximately 100 linear meters of documentation that now make up the GAM archive.

Archival Partnerships

In the fall of 2016, librarians at Haverford College, a small liberal arts college outside of Philadelphia, and GAM members held their first Skype call. They were introduced by political science professor Anita Isaacs, who told the librarians that an important human rights organization had a closetful of endangered documents. These boxes and bags of materials were under threat of possible sudden seizure, destruction, or continued degradation due to the humid climate and the passage of time. The collections had already survived multiple office moves, police raids, and bombings. The organization’s lack of material resources to provide adequate perpetual storage conditions posed just as much of a threat, though a less dramatic one.

Continue reading the rest of this article here, available open access for a limited time.

The digital archive was made possible with the contributions of Haverford College students: Yasmine Ayad, Rosemary Cohen, Luis Contreras-Orendain, Ashley Guzman, Chloe Juriansz, Natalia Mora, Saúl Ontiveros, Tania Ortega, Federico Perelmuter, Mariana Ramirez, Rafael Rodriguez, and Fiona Xu.

Daniel Alvarado is a human rights advisor at the Grupo de Apoyo Mutuo, co-coordinator of the GAM Historical Archive, and graduate of the University of San Carlos programs in Pedagogy and Human Rights. He is also a representative to the Regional Human Rights Monitoring and Analysis Team for Central America and a member of the Working Group Against Forced Disappearance in Guatemala.

Carlos Juárez is a lawyer at the Grupo de Apoyo Mutuo and co-coordinator of the GAM Historical Archive. Follow Carlos on Twitter: @carpjuarez1

Brie Gettleson is a social science librarian and a visiting assistant professor of anthropology at Haverford College. She wants to give special thanks to Heather Gies for the insightful comments in the editing process and to Natalia Mora for translation assistance. Follow Brie on Twitter: @brie_marina