On March 7, a protest against abuse and neglect at the Hogar Seguro "Virgen De La Asunción, a state-run “safe house” for minors outside of Guatemala City ended in a deadly fire that killed at least 40 adolescent girls— with ongoing impunity for those responsible. The deaths of the young women at the distinctly un-safe shelter where they were almost certainly subjected to sex trafficking, sexual assault, rotten food, and neglect demonstrate the Guatemalan state’s failure to “guarantee the life, liberty, justice, security, peace, and the integral personal development” of its most vulnerable citizens, rights that its Constitution guarantees. That’s not to mention the government’s ongoing failure and unwillingness to prevent and protect women from violence and femicide.

On the afternoon of March 7, 2017, dozens of young residents at the Hogar Seguro la Virgen de Asunción in San Pedro Pinula, Guatemala tried to draw attention to the horrific conditions at their “safe shelter.” Though the specially appointed Defender of Childhood and Adolescence at the government’s Office of the Human Rights Ombudsman had ordered the facility to be closed in November 2016 due to poor conditions, nothing had happened. The minors cited a long list of mistreatment and, echoing a tactic used by incarcerated people around the world, started mattress fires to draw attention to their situation and attempted dangerous escapes. Around sixty residents escaped that night before they were caught by officers of the Civil National Police (PNC) and promptly returned to the shelter. The adolescents’ attempt to pressure the state into improving conditions at the shelter and express their rage and disgust found their efforts met with force rather than open ears.

The over-crowded Hogar Seguro (“Safe Shelter,” in English) held around six hundred minors in facilities intended for four hundred; this was a significant decrease from 2016’s shelter population of more than seven hundred residents. Its population included infants of a few months to teenagers up to eighteen years of age. According to the Social Welfare Secretariat, residents were sent under court order to live at the hogar because they were victims of physical or sexual abuse, abandoned by their families, involved in sex trafficking, charged with gang involvement (including extortion, homicide, and drug trafficking), lived on the street, suffered from addiction, lived in legal limbo after illegal adoption, or had “light” cognitive disabilities. In other words, the hogar was meant to offer safety and stability to a wide array of at-risk youths. But in practice, conditions were so bad that about forty-five reports of abuse had been filed with the office of the Human Rights Ombudsman since 2012. Residents regularly escaped or disappeared at night, events widely suspected to be linked to sex trafficking.

On the night of the 7th, around a hundred police officers were sent to the shelter to capture the escaped adolescents and stop the protest. Several YouTube videos show that the police outnumbered the youths and that they corralled the several dozen who escaped against an exterior wall of the compound on the sidewalk outside the shelter. The youth seem sometimes cowed and scared, and at others times loud and defiant. In one video, heavy black batons wielded by the police glisten in the flash of cameras. In another shot, a group of girls show the horizontal cuts across their wrists and forearms and what appears to be a piece of glass used to cut their wrists. The youth shout as the police threaten from behind a wall of riot shields. One officer lunges at a young boy.

The following morning at breakfast time, a fire burned inside the Hogar Seguro. Many of the young women who had escaped the night before were locked into a single room as the fire spread, perhaps as punishment for the previous night’s protest, the Office of the Human Rights Ombudsman (PDH) reported. Though the precise origin of the fire remains unknown, rumors that circulated after the fire described the presence of flammable materials, including gasoline, inside a locked room, which exacerbated the fire that may have been started by girls trapped inside. Information about the key that would have unlocked the door is still unknown. Some reports recounted that firefighters did not receive a fire alert from staff at the shelter for nearly an hour, and once they arrived, the police illegally guarding the building forbade them to enter. Other reports stated that firefighters did not enter the facilities until the fire had nearly stopped. Emergency vehicles took injured minors to nearby hospitals in Guatemala City; others in critical condition were flown to hospitals in the United States for specialized care. Around nineteen were declared dead at the scene and transported to morgues to be identified by fingerprints.

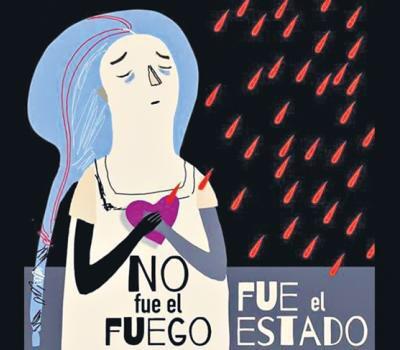

Quickly, social media lit up. Social justice organizations and activists based in Guatemala City quickly held the state accountable, circulating memes declaring, “Estado asesino” (murderous state). Later in the day, President Morales announced three days of mourning nationwide. For its part, the Social Welfare Secretariat denounced the youths’ protest as an action carried out by adolescents imprisoned for participating in extortion, suggesting that the protest was an act of violence masterminded by gangs and carried out by drugged-out youth. Workers at the shelter reported that two girls started the fire by igniting a mattress during breakfast. In the fire and in hospitals in the week after, 40 young women lost their lives. Many were rumored to be pregnant, a detail that has not yet been clarified by autopsies or forensic investigations. As hours passed, mothers began to gather at the Hogar Seguro to wait for news about the children who had been placed in the state’s custody.

The Hogar Seguro is one of many shelters, hospitals, and asylums intended to provide a safe space for children, youths, and adults confronting a dizzying array of circumstances that keep them from living orderly lives in the eyes of the judicial, law enforcement, medical, or social welfare systems. These hogares are part of Guatemala’s long history of beneficence, dating to sixteenth century asylums created to provide homes for elderly indigenous laborers.

The mistreatment of these most vulnerable people also has a history, including the use of pyrotherapy (stimulation of fever [oftentimes using malaria infection] to treat neuro-psychiatric conditions) and other experimental treatments at the Asilo de Alienados (Insane Asylum) since the 1930s and the infamous syphilis and gonorrhea experiments carried out by U.S. physician John C. Cutler between 1946 and 1948 at the same hospital. More recently, investigations by the disability rights group Disability Rights International (DRI) in 2012 and the BBC in 2014 revealed a shocking scene of neglect at the renamed asylum, the Hospital Nacional de Salud Mental Federico Mora (Federico Mora National Mental Health Hospital). Seemingly little has been done to investigate these complaints.

Guatemala’s entrenched impunity has not just protected high-profile politicians like Efraín Ríos Montt from serving sentences for crimes like genocide and crimes against humanity. It has also protected lower-level government officials from prosecution by delaying court processes, shifting blame up and down chains of command, providing poor training for forensic techniques, and bestowing special protections onto appointed and elected officials. Exemplifying this culture of impunity, Morales appeared before national and international news agencies to insist that the fire was “everyone’s responsibility” without naming any specific guilty parties.

For some Guatemalans, the fire sparked a sort of national soul searching. What kind of society would permit these young women to be warehoused, mistreated, their cries unheard?

But for many others still, this instance of sexual assault and state violence—and impunity—is just one more illustration of the government’s indifference toward poor Guatemalans. For instance, HIJOS-Guatemala, a group of sons and daughters of people disappeared or killed in the civil war, released a statement that compared the fire at Hogar Seguro to the military’s civil war “scorched earth” campaigns that destroyed communities in the departments of El Quiché, Alta and Baja Verapaz, Chimaltenango, and Huehuetenango and killed thirty-seven people at the Spanish Embassy in 1980. HIJOS wrote, “Today as before, the punishment for dissent and resistance to the system that imposes the logic of capital[ism] is fear, terror, and being burned to death.”

Social media and “hashtag activism” has helped Guatemalans reach beyond the limits of the press. Since the fire, the hash tags #FueElEstado and #GuateDeLuto have signaled the state’s responsibility for the loss of life. #TragediaEnHogarSeguro has insisted on the extraordinary nature of the fire. The hashtag #DeRegresoALaPlaza called on civil society to come back to the Central Plaza where they’d successfully ousted corrupt ex-president Otto Peréz Molina in 2015 to demonstrate against state violence and impunity. #NosFaltan40 (“40 are missing”) employs a familiar idiom of human rights to hold the state to be accountable for each individual life lost.

In the days after the fire, protestors wrote denunciations on a long slab of wood placed in front of the National Palace. Two read, “It was not a fire, it was femicide” and “Failed state, corrupt state, murderous state has killed our girls.” Another: “The fire did not kill the girls. Society’s indifference and the ineptitude of a failed state assassinated them.” Still others read: “Crime: girl and poor; sentence: rape and burning at the stake [hoguera].” The most concise was a denunciation that simply stated: “The State kills you.”

Since 1945, the Constitution of the Republic has opened with an affirmation of the state’s duty to guarantee the life, liberty, justice, and security of all inhabitants of the Republic. With little variation, these guarantees endured through the civil war while the government systematically targeted its Mayan citizens, evincing a foundational hypocrisy and the endurance of impunity. Faced with this deep history of state violence and impunity, human rights advocates around the globe and especially in Guatemala have pursued a consistent strategy of tracing the chain of command and prosecuting the highest official responsible for the crime under consideration.

In this case, the chain of command extends from the director of the shelter (Santos Torres Ramírez) to the Secretary of Social Welfare (Carlos Antonio Rodas Mejía, who resigned from his position a few days after the fire) to the President, as the highest authority of the Executive Branch to whom the Secretary of Social Welfare directly reports. In the week after the fire, Ramírez, Rodas Mejía, and Anahy Keller Zabala, of the Secretariat for Protection of Children and Adolescents, were arrested for culpable homicide, breach of professional duty, and child abuse. So far, no PNC officers have been arrested or charged.

What would change if these three state functionaries were brought to trial? The criminal justice system that eagerly incarcerates and criminalizes juveniles has demonstrated over and over again its reticence to prosecute cases of corruption and crimes against humanity and genocide. As of 2012, only 2% of crimes reported to the public ministry resulted in convictions, according to Freedom House. Even if they were convicted, would these convictions bring justice to the people of Guatemala? Only in the shallowest sense. How are we supposed to look toward the state for a solution—the same state that has already failed to care for the youths?

What, then, is to be done?

If the government were to close the dangerous hogares, they would leave thousands of young people to fend for themselves on the streets. States across the hemisphere have been shrinking budgets for public funding of shelters and hospitals for their most vulnerable citizens. At the same time, shelters like the Hogar Seguro la Virgen de Asunción remain important as spaces where the state takes over care for at-risk youth. The trend toward deinstitutionalization and privatization of state-led mental health services that has swept the mental health community in recent decades has left people in desperate need and few resources without a place to go.

For their part, HIJOS-Guatemala made several recommendations in an official press release a few days after the fire. The group demanded the following: protection for the survivors of the fire, so that they can serve as witnesses in an investigation of the fire; special protections and care given to survivors of trauma; the creation of a multilateral supervisory board to guarantee that these types of crimes do not continue to happen. and for the preventative detention of those responsible for the events under investigation, under the label of femicide. It can’t be ignored that the fire occurred on International Women’s Day, March 7, 2017 and just two weeks after President Jimmy Morales ordered the army to detain a Dutch ship that sought to provide women with safe abortions (abortions are illegal in Guatemala except in cases where the mother’s life is in danger).

HIJOS also demands the immediate intervention of the UN-backed International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) in the investigation in order to preserve forensic information at the scene of the crime. The document also stresses the need to investigate several specific questions, including why the police had illegally taken control over the center, why they did not allow the firefighters to enter the building or the children to leave, and why reports of mistreatment at the Center were not investigated or prosecuted by the Interior Ministry.

For another preventable act of violence, Guatemalans and allies around the world once more demand justice from a state that is utterly unable – or unwilling— to offer it.

This is the precariousness and the criminalization that so many young women are fleeing when they cross the border to Mexico, and then travel northward through extreme conditions to cross another border to enter the United States, where their fates remain insecure.

Heather Vrana is Assistant Professor of History at Southern Connecticut State University and the author of This City Belongs to You: A History of Student Activism in Guatemala, 1944-1996 (University of California Press, forthcoming) and editor of Anti-colonial Texts from Central American Student Movements, 1929-1983 (Edinburgh University Press, 2017).